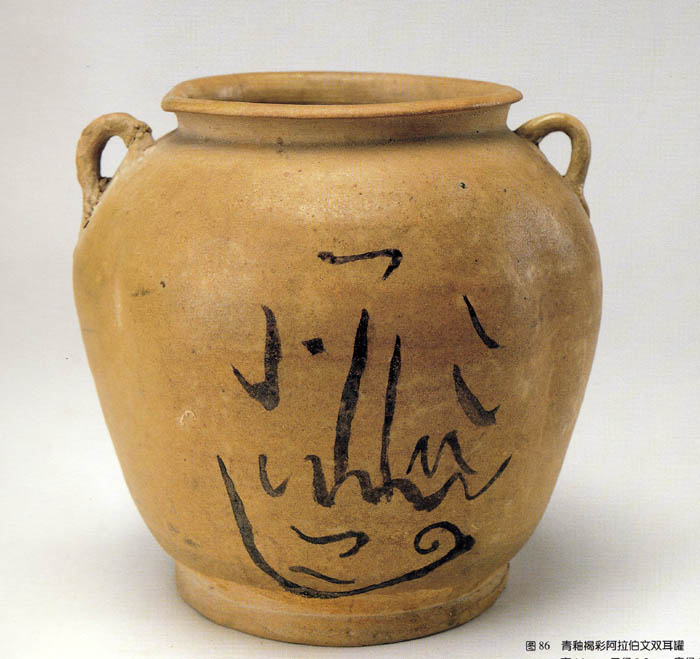

Tang Changsha Jar with Arabic script found in Yangzhou

The magic square has its origins in China. According to ancient Chinese literature dating back to around 650 BC, during the reign of the mythical King Yu (禹), a turtle emerged from the Luo River during a great flood. The turtle's shell featured a 3x3 grid pattern with circular dots representing numbers. The sum of the numbers in each row, column, and diagonal equaled 15, corresponding to the number of days in each of the 24 cycles of the Chinese solar year. This pattern, known as the Lo Shu or "scroll of the river," was believed to help control rivers.

In ancient times, magic squares were thought to possess astrological and divinatory qualities, promoting longevity and warding off diseases. Islamic mathematicians adopted the concept as early as the 7th century after coming into contact with Indian and Chinese cultures.

According to Prof. Schuyler Cammann of the University of Philadelphia, the magic square symbolically represents Islamic cosmology, illustrating the belief that Allah is both the Source and Destination of all things. Plates and bowls featuring magic squares were used as medicine bowls in the Islamic world, believed to possess protective powers against

The motif on my bowl piqued my interest. Its shape and fine paste indicated that it was an 18th-century product from the Jingdezhen kiln. I was thrilled to come across an article titled Some Chinese Islamic "Magic Square" Porcelain in the book Studies in Chinese Ceramics by Prof. Cheng Te-kun. He noted that a group of Chinese export wares featuring Islamic inscriptions and magic squares appeared in the Singapore antique market in 1969 and were eagerly acquired by local collectors.

Prof. Cheng's research included a porcelain plate with a similar design that was presented to Queen Mary of the United Kingdom during her 1906 visit to Hyderabad, India. This plate, once a treasure of Golconda Fort, is now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was also a product of the Jingdezhen kiln, dating to the 18th century.

The plate featured Koranic verses and Islamic prayers. With assistance from Dr. Hassan Javadi of the University of Tehran, Prof. Cheng deciphered most of the inscriptions despite errors made by Chinese potters unfamiliar with Arabic. For example, the first band near the rim contained verses 256 and 275 from the Koran:

"In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate God, there is no god but He, the Living, the Everlasting. Slumber seizes Him not, neither sleep: to Him belongs all that is in the heavens and the earth. Who is there that shall intercede with Him save by His leave? He knows what lies before them and what is after them, and they comprehend not anything of His knowledge save such as He wills. His throne comprises the heavens and earth; the preserving of them oppresses Him not: He is the All-high and the All-glorious."

Surrounding the magic square, the inscriptions read:

“There is no man like Ali (Cousin of Mohamed). There is no sword like Zulfakar (his sword)."

The square was subdivided into 16 smaller squares, each containing a two-digit number in black. The magic square was of the fourth order, with the sum of the numbers in any vertical, horizontal, or diagonal direction totaling 194.