Study of Chinese Ceramics in the Tang Belitung wreck

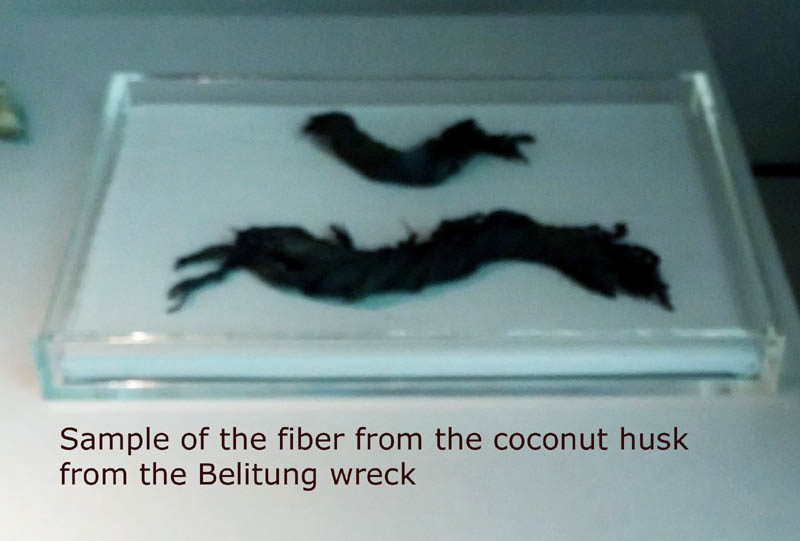

The wreck was discovered by fishermen in 1998 in the Gelasa Strait. It was salvaged by Seabed Explorations with the consent of the Indonesian government. The cargo was purchased for around USD 32 million by a private company, the Sentosa Leisure Group, and the Singaporean government in 2005. The Belitung shipwreck (also called Batu Hitam shipwreck) is one of the greatest maritime finds. It throws light on the nature of maritime trade during the 9th century between the middle East and China. The cargo is a time capsule which revealed the mix of Chinese ceramics that were produced and exported. Study of the wreck confirmed that the "lashed-lug" method using fibers to stitch the planks together was used to construct the ship. According to Michael Flecker, the marine archaeologist involved in the salvage of the Belitung wreck, fully stitched boats were found in the region covering the Eastern African coast, Oman in Middle East and as far as the Maldives. Arabic and Chinese ancient texts revealed that Persian/Arab merchants played a key role in the sourcing and distribution of the Chinese goods to the West. The late Tang Ancient Chinese text " Ling biao lu yi" ("Strange Things Noted in the South") by Liu Xun(嶺表錄异 / 劉恂撰) described the ships of foreign merchants as being stitched together with palm fiber and the seams sealed with resin" . This wreck is the first physical proof that the Arabian dhow was the vehicle for transporting of goods from China to the Middle East.

Model of the Arabian dhow Singapore Asian Civilisation Museum

Dating of the Wreck

Radiocarbon dating of the ship's timber produced a relatively wide range date of 710 - 890 A.D for the wreck. A Changsha bowl with a partially illegible inscription on the external wall appears to include the words "宝历二年七月十六日“ ie Baoli Ernian Qiyue Shiliu Ri, which gives a dating of 826 A.D. In the book "Shipwrecked Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds", some ceramics scholars have offered views pushing the date forward by 2 to 3 decades. Another Changsha bowl with decoration including two flags was interpreted as carrying the cyclical date "丙子” Bing Zi equivalent to the date 856 A.D. This is most likely erroneous as the character 子 on the left flag do not have the horizontal stroke. It is more consistent to read as 丁 (Ding). Hence, the characters should be 丙 丁. The decoration is more likely depiction of military encampment of tent and flags. The characters 丙丁 which represented the fire element was used to identify a sector of the military troop in battle formation and mobilisation. The concept of the 5 elements, ie metal, wood, water, fire, expounded in Yijing (The book of Change) was utitlised by ancient Chinese military strategists in the art of war. There are some who visualise the tent as a bell with Buddhist “卍” symbol. But if we examine the motif carefully, we can see that it is not round but more squarish form with edges. But why the “卍” symbol on the tent ? It is puzzling and an egnima. From what I gathered, “卍” was an archaic symbol used in many ancient cultures and one of its symbolism was that of the sun or fire. Did the potter used both to reinforce the representation of fire?

The Characters on the flag should be 丙丁

Personally, I am of the view that the cargo was assembled and shipped shortly after 826 A.D and the Chinese ceramics were commercial goods and unlikely to be made much later or earlier than 826 A.D. Hence, they were still produced during the Mid Tang period (766 - 835 A.D). As it was already towards the closing years of Mid Tang, some of the vessels may exhibit certain characteristics found in late Tang period. But overall, we can still see that majority still display more distinctive features found during Mid Tang.

Among the Changsha wares, there were some dishes with an unglaze square area. Zhou Shi Rong (周世荣), the Chinese expert on Changsha ware mentioned in his book that such dishes were found in the grave of Wang Qing (王清) located in Changsha and dated 6th year of Da He (大和六年), ie 832 A.D.

Belitung Changsha dishes with unglaze square area

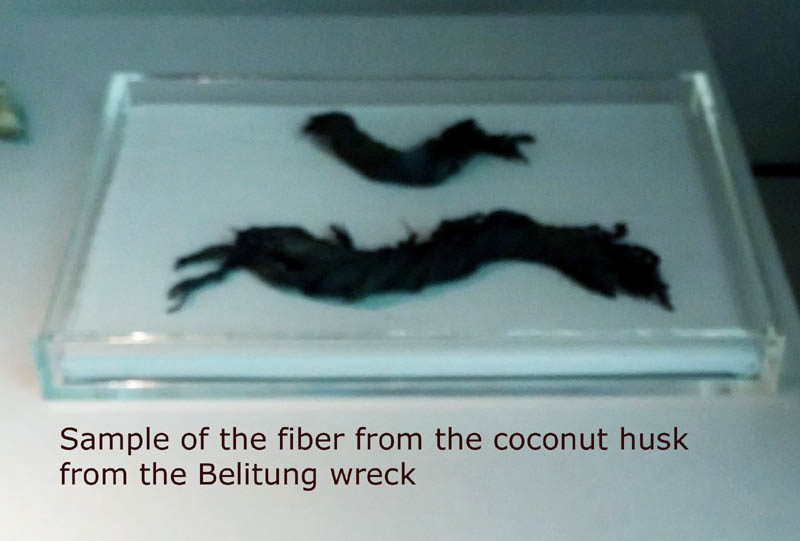

A mould of a lug with an inscription Yuan He San Nian (元和三年), ie 3rd Yuan of Yuan He (808 A.D), has also been recovered from the kiln site. It is similar to one found on the below Belitung Changsha jar. Such lug is known to be popular during early 9th century.

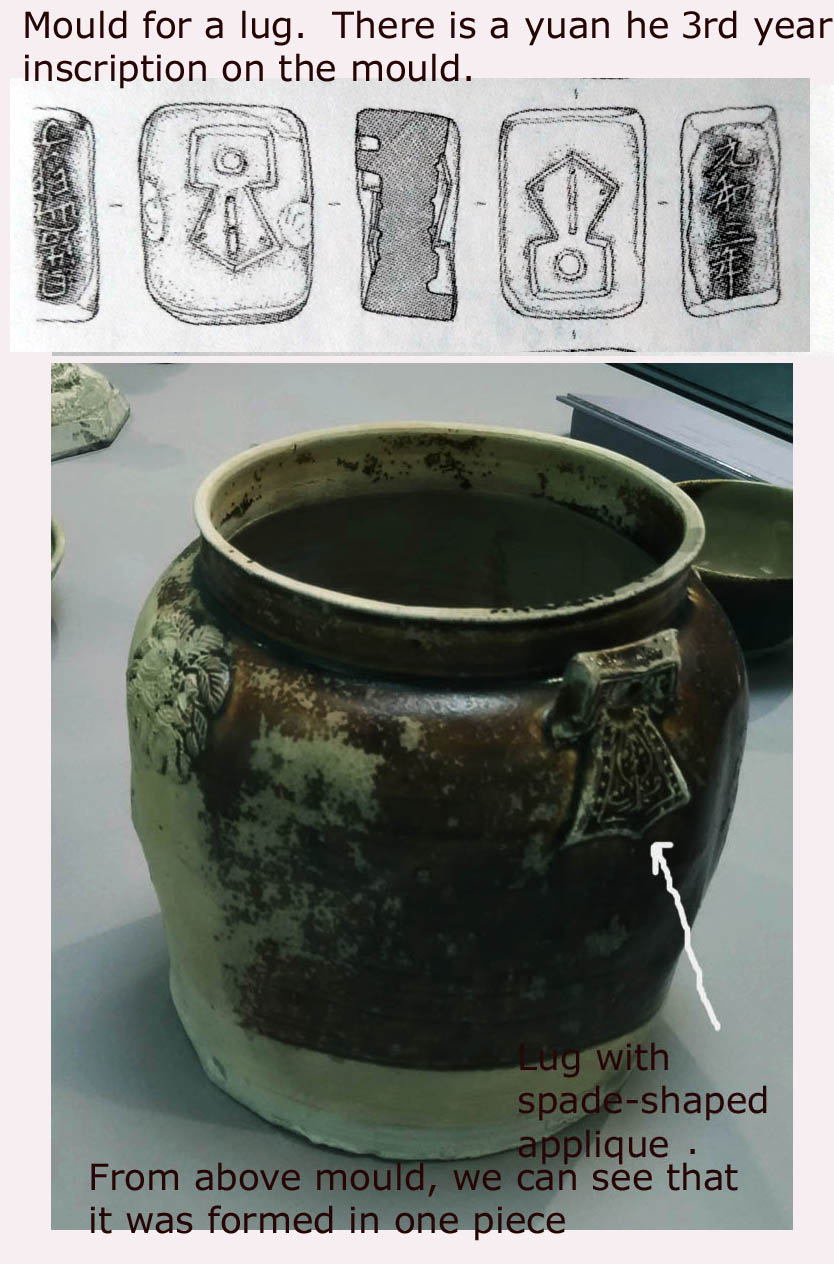

The shallowly carved decorative style on of the Yue wares offers another clue for dating. The carved line surface is slightly angled. From literatures written by Chinese experts who specialised in the study of Yue wares, the evolution of decorative techniques placed such technique as prevalent during the Mid Tang (766 - 835 A.D) while incising was introduced and more popular from the late Tang (836 - 907 A.D) period.

All the ewers have short spout, a feature typical of early/Mid Tang ewer. By late Tang, the spout become more elongated and the ewer is more elongated in form.

Tang Ancient Maritime Trade Route

The ancient text on the history of Tang, Xin Tang Shu (新唐书) from the Early Northern Song, included information regarding the martime trade routes. It was based on an earlier work (785 - 805 A.D) "Guangzhou Tong Hai Yi Dao" 广州通海夷道 by Jia Dan贾耽 which recorded the details of the maritime trade route linking China to the West and East. The maritime route originated from Guangzhou and listed the key places in Southeast Asia, West Asia and Middle East which the ships passed and probably visited. The main trade route is traced with white dotted lines on the map below. The aforementioned text also disclosed an alternative spur route to Central Java, the power base of the Mataram Empire. Hence, it is likely that the Arab ship found wrecked near Belitung was on its way to Central Java.

Ancient maritime travel between East and West was dictated by the monsoon wind. The present day Sumatra in Indonesia/East Malaysia was an ideal region to break the journey and await the change of wind to bring one to the next destination. Besides supplying regional exotic, aromatic products and spices desired by merchants from the East and West, it also served as entrepot and emporium for the trading of goods between the East and West region.

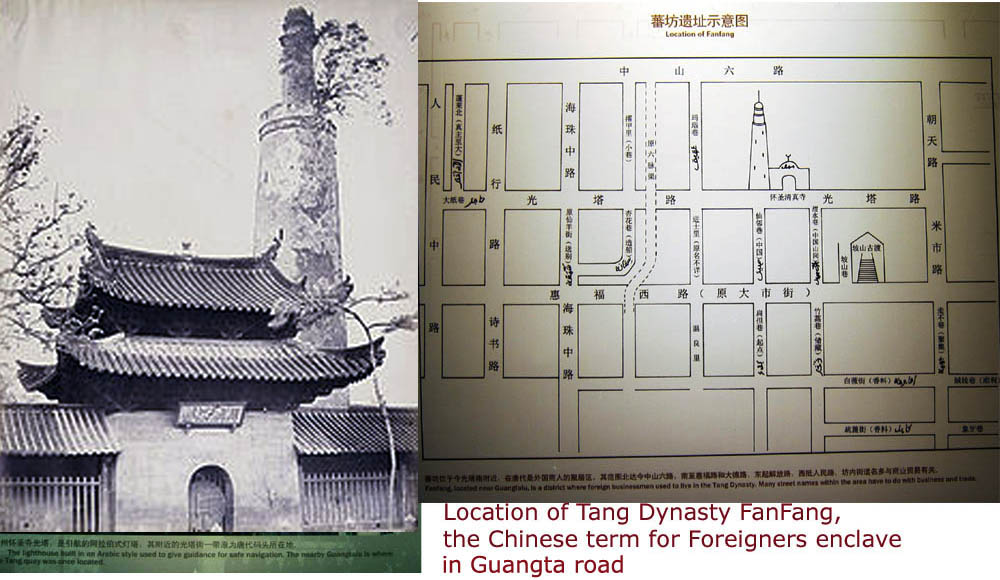

During Tang Dynasty, Guangzhou was designated as the main gateway for the martime trade. Ancient Chinese fragmentary references suggested that the post of Shi Bosi (市舶使), ie the Superintendent of Maritime Trade was established to supervise and regulate foreign trade, collect tax, purchase foreign goods for the palace and manage tribute related matters. In Guangzhou a designated enclave termed Fan Fang (番坊) was built for foreigners to stay and transact business. It was located near Guangta (光塔路) road. . Many of the street names in the area were related to the type of business/trade. The Arabic style Guangzhou Huaishen mosque (广州怀聖清真寺) lighthouse located in the vicinity was a landmark that used to guide ships entering Guangzhou port during the Tang Dynasty.

According to the ancient text Akhbar al-Sin wa'l-Hind (An Account of China and India) compiled by Sulayman al-Tajir, Khanfu, ie Guangzhou was the premier port for western trade. Another important reference is "The Book of Roads and Kingdoms", a 9th-century geography text by the Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh. It maps and describes the major trade routes of the time within the Muslim world, and discusses distant trading regions including China. It was written around 870 CE, while its author was Director of Posts and Police for the Abbasid province of Djibal. He noted that there were 4 famous ports in China, listed in sequence as al-wakin (Hanoi), Khanfou (Guangzhou), Djanfou and Kantou (江都 )(Yangzhou). Most scholars were in agreement on the interpretation of 3 while Quanzhou and Fuzhou were offered as candidate for Djanfou. In the Chinese academic circles, there were much discussions and debates on whether there were designated institution headed by Shi Bo shi in those ports including another one Mingzhou (Ningbo). Other then Guangzhou, there was very little documentary evidence to support the arguments for the existence of Shi Bo Shi in the other ports. However, the information in Ibn Khordadbeh's book and archaeological findings in Yangzhou and Ningbo strongly supported the presence of past active maritime trade activities. Hence, although they might not be significant enough to warrant creation of a designated institution manned by a Shi Bo Shi, it is likely that other officials may have been assigned additional duties and role similar to that of the Shi Bo Shi. Interestingly based on archaeological findings, Yangzhou and Ningbo produced more physical evidence in terms of ceramics fragments that were similar to that from the Belitung wreck. In Yangzhou, many complete and sherds of Changsha wares, Yue greenwares and white wares were recovered from the sites that were in Tang Dynasty the commercial and residential sector called Luocheng (罗城).

|

| Model in Yangzhou Museum of Ancient Yangzhou Commerical sector Luocheng (罗城) and administrative sector Yacheng (子城) |

The Grand Canal built during the Sui Dynasty joined the major river systems from different directions and became the main conduit for the transportation of grain/salt and other essential and luxurous goods. Yangzhou was strategically located at the cross road of the Grand Canal and Yangzi river . During Tang Dynasty, it became the most prosperous commercial centre and the emporium for grain/salt and all the essential and luxurious goods. From here, the good were ferried to the capital Luoyang and Northern China. The goods could also be transported by ships along the Yangzi river towards the sea on the East and made their way overseas. From the below map, we can also see that Changsha, Xing and Gongyi kilns were located near the riverine/canal network. Hence their ceramics products could access this network and ferry to Yangzhou. Yue wares could also made their way by the sea route to Yangzhou.

Changsha wares from ancient Yangzhou sites

Besides Changan and Guangzhou, Yangzhou also attracted large community of foreign traders, mainly Persians and Arabs, to set up shops to do business. The Tang Court understood the importance of the Nanhai trade and in 834, the emperor Wen Zhong issued an edict to remind the officials to treat the foreign merchants, stationed in Lingnan (referring to Guangdong), Fujian and Yangzhou, who were engaged in the Nanhai trade well. From the content, it could be inferred that the foreign merchants were free to trade at any of the aforementioned ports. Hence, in view of its important commercial role, it was suggested that the Arab dhow which carried the Belitung cargo had called at the Yangzhou port to source the goods. Although this possibility should not be discounted, other scenario should also be considered.

Documentary evidence from Chinese and Japanese sources indicated that Mingzhou (Ningbo) and probably Yangzhou were the ports which handled most of the trade with Korea and Japan. From economic point of view, their geographical proximity to Korea/Japan meant they were ideally located to handle the Eastern direction maritime trade. Similarly, Guangzhou on the south was more ideally located for the Nanhai trade. Ancient texts had also repeatedly highlighted its importance in relation to the Nanhai trade. As the premier port, it was an emporium for both imported and exported goods. Both land and coastal shipping network would have existed for it to access all the required essential and luxurious goods. As Yangzhou was a major commercial centre, trade relation between it and Guangzhou must have been close and intense. Close business network would have existed between the foreign merchants from both centres and facilitated the flow of goods by the coastal marine route. Hence, whatever goods in demand must have been also readily available in Guangzhou. It would not make economic sense for the dhow to travel all the way up to Yangzhou if the goods could be sourced in Guangzhou. Furthermore, among the cargo there were two white bowls with green splashes, one with incised character Ying (盈) and the other Jin Feng (进奉). Vessels with such inscribed characters were made as local tributes to the palace. Hence, the appearance of such bowls in the cargo would suggest that there could be a group with diplomatic mission. Those gold and silver and high quality ceramics may be gifts from the Tang emperor to the ruler of the Abbasid empire or the central Java Mataram Kingdom. If indeed that is the case, the Shi Bo Shi at Guangzhou would be the most appropriate official to receive the diplomatic mission. Hence, it would render additional weight to the argument of it being the port which the Belitung cargo was assembled.

Personally I am more in favour of the latter argument, ie Guangzhou was the point of assemblage of the cargo. However, one have to concede that the current level of knowledge on the marine time trading and logistic networks is still too patchy and incomplete to form a definitive conclusion.

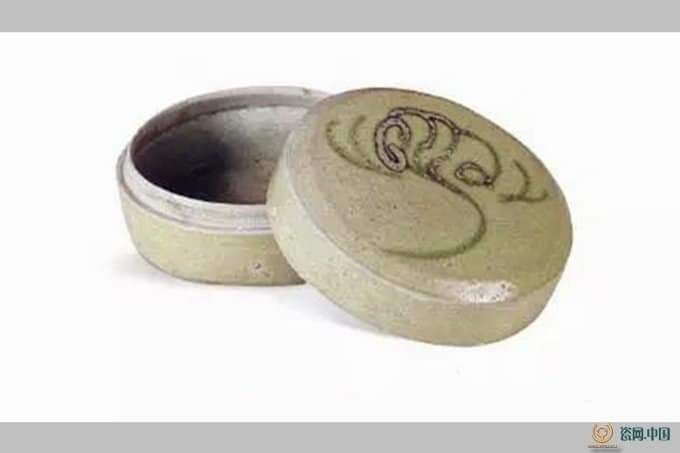

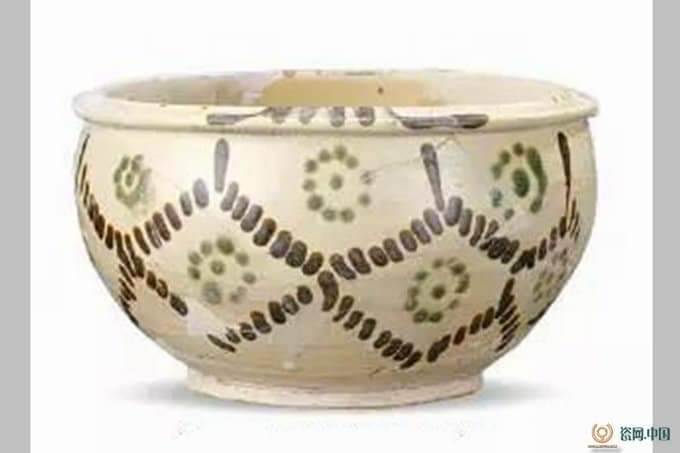

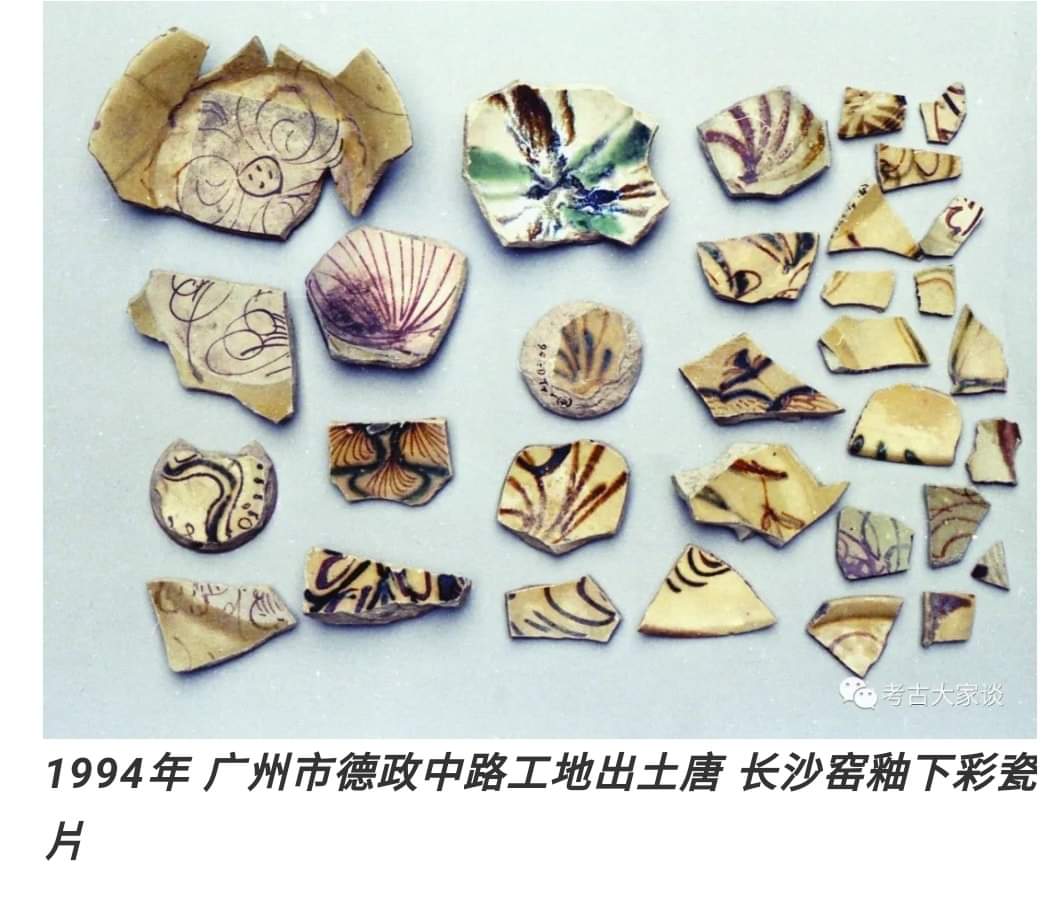

Changsha fragments from a site in Guangzhou

Bowl with the inscribed Ying (盈) character, ie surplus

From the western and Chinese ancient texts, it is clear that Siraf was the terminal port on the western end of the maritime trade route. It was the premier port of the Abbasid empire. From here, the goods could be distributed to cities on the east or shipped to Basra and further transported to the Capital Baghad. It was also in Siraf that the goods from the Abbasid empire were gathered and shipped East. Its role as the entrepot ended after it was devastated by an earthquake in 977. Archaeological excavations revealed that Chinese Ceramics similar to that from the Belitung wreck were found in significant quantity in key points on the maritime trade route such as Palembang, Borobudor and Prambanan temple sites in Central Java, Mantai in Sri Lanka and the Great Mosque of Siraf.

Analysis of Chinese ceramics in the Wreck

The Chinese ceramics cargo consisted of Changsha, Yue, Xing and Guangdong wares. This was the typical cargo assemblage which is consistent with what we would expect for this period. Changsha wares, majority consisting of bowls, formed the bulk with around 55,000 complete pieces recovered. It was undisputedly the most highly demanded Chinese export ceramics of the era. The quantity in this wreck and their relative larger quantity in important arachaelogial sites in Yangzhou in China, Yangzhou, Laem po in Southern Thailand, Sumatra and Central Java in Indonesia, Mantai in Sri Lanka and Siraf in Iran is testament of its dominent market position. It's painted decorations apparently appealed to the asethetic needs overseas mass consumer markets.

Undeniably, Yue greenware and Xing white wares were more expensive and intended to cater to the high end market. Hence, the quantity found in the wreck were small in quantity, ie around 200 pieces each. In terms of the glaze and potting, they were far more superior to what the Changsha potters could produce. Domestically, they were widely recognised brands and much appreciated and praised by the Chinese literati class. Yue greenware and Xing white ware represented the definitive ceramics production trend of the Tang Dynasty, ie Greenware in South and White ware in the North (南青北白). Changsha ware is usually classified as greenware and little attention is paid to its achievement in terms of high fired polychrome decoration in copper green/red and iron brown. This is in fact a technical breakthrough as in the past only one colour ie iron brown was used for high fired decoration. This should be differentiated from the technically different low-fired lead glaze Tang polychrome Sancai. It is an important milestone in Chinese decorative art on Ceramics.

A short video clip on the ceramics cargo in the wreck on display in the Asian Civilisation Museum can be viewed here.

Changsha Wares

Changsha wares were produced in kilns in Tongguan (铜官) town and Shizhu (石诸) region, about 30km north of Hunan Changsha. It is also termed Tongguan kiln (铜官窑) or Wa Zhaping kiln (瓦渣坪窑), the local name for the area in Shizhu because of the huge heaps of ceramics waste. Some of the waste is as thick as more than 4m, a testament to the enormous production scale. Archaelogical surveys confirmed that the kilns were mainly located along the east bank of the Xiang river (湘江) which flows pass the Shizhu region. Changsha wares, mainly produced for the overseas market, could be ferried along this river to Dong Ting lake (洞庭湖) and from there to the Yangzi river and made its way to Yangzhou, the most important commercial centre of the Tang era.

One of the Changsha kiln sites has been developed as a tourist attraction

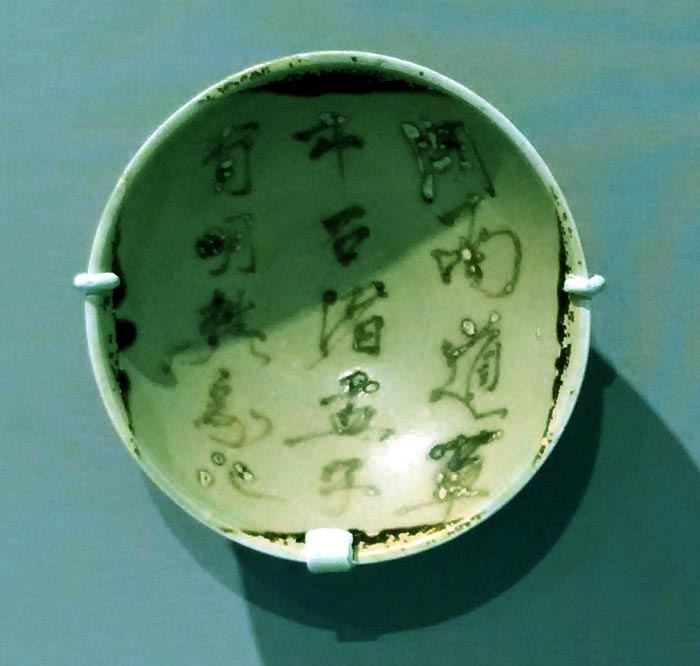

Despite its popularity, it is indeed strange that there were no ancient text that commented about this ceramic product. We only learn about this category of Tang ceramics after the kilns were discovered in 1950s. Ironically, if the Belitung wreck was discovered earlier, the identity of such wares would have been disclosed. In the wreck, there is a bowl which provides unrefutable evident of its identity. It has the following calligraphic inscription "湖南道草市石诸盂子有名有名礬家记". The meaning is as follows: "湖南道 Hu nan dao" refers to Hunan the region, "草市 cao shi" ie market, "石诸 Shi Zhu" ie the specific town, "盂子 Yu zi" ie name of a vessel, "有名 you ming" ie famous and lastly "礬家记 Fan Jia Ji" ie the name of the workshop. In short, the clue indicates that it was made in Hunan in a location called Shi Zhu. Furthermore, this was also probably at least one of the earliest known example of advertisement promoting one's product.

Important Changsha bowl which indicates it was made in Hunan Shizhu

Archaeological surveys showed that Changsha wares were first produced during 2nd half of the 8th Century and reached its peak during the Mid/late Tang period. Initial products were similar to those monochrome greenware made by Yue (岳) kiln. This Yue in Chinese is a different charactor and should not be confused with the famous Yue kiln from Zhejiang. It was also a famous greenware from Hunan and mentioned in Lu Yu (陆羽)'s Cha Jing (茶经), ie Treatise on Tea. The devastating An Lushan Rebellion (755- 763) in Northern China resulted in mass migration of refugees to the South. Some of them were potters from Hebei/Henan who ended up in Hunan. Those potters were instrumental in imparting new ceramics production technology to the locals. It is believed that the distinctive Changsha high-fired painted wares was developed from the foundation of low fired lead glaze sancai.

Yue were Changsha wares are usually associated with the painted polychrome brown/green decoration and those with applique motifs. The colour of the glaze varies from a light grayish green to a creamy yellowish white. The glaze could appear transparent or translucent and milky. A white slip is applied to conceal the coarse body before the glaze is applied on the vessel. The glaze has a tendency to peel off, especiallythose brown glaze area. The glaze usually have fine crazings. The body can vary from a more typical grayish colour to those with buff or varying brick colour tones.

The vessels from this wreck consisted of mainly bowls, some quantity of ewers and small number of censers, cups, cover box, sculptural toy of animals and birds and etc. Domestically, the bowls with a dia. of about 15 cm were mainly used as tea bowls. In the wreck, there is a bowl with the word Tu Zhan Zi (荼盏子) ie tea bowl. During pre-Tang, Tu was the character for tea. It was replaced by Cha (茶) during Tang Dynasty. Its usage on this bowl suggested that both were still used interchangeably even during the Mid Tang period.

The bowls were probably used for different purposes in the overseas market. Bowl with dia. of 15 cm constituted the bulk. However, there are also significant quantity of larger bowls with a dia. of about 18 cm. Bowls of other sizes and shape are rare in this wreck.

The decoration are painted with pigment with iron-oxide or copper as the colourant. The wares were fired in the kiln under oxidation atmosphere which resulted in iron-oxide inducing a brownish and copper oxide a greenish colour. Among the vessels, we found some rare examples with successfully fired copper red. Copper will only induce a red colour in reduction atmosphere and it is very difficult to produce good red colour due to the highly volatile nature of copper.

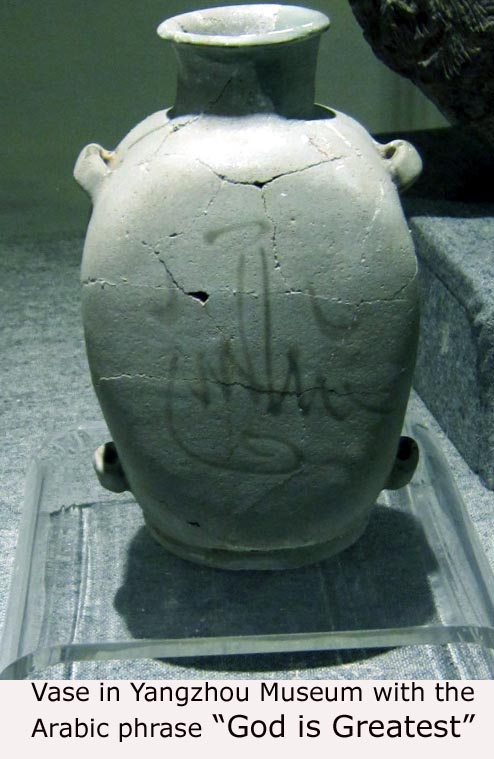

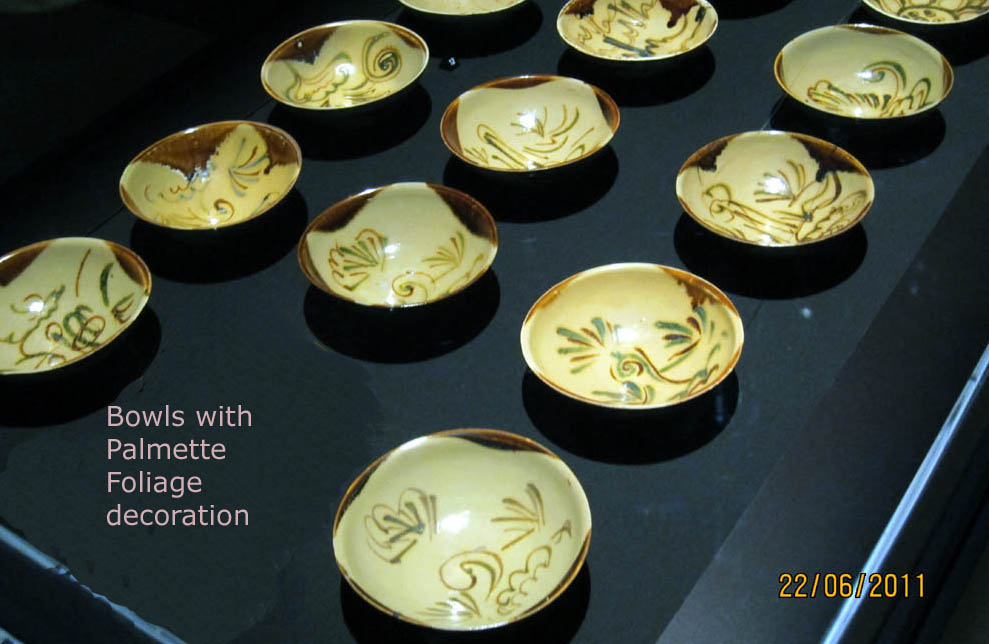

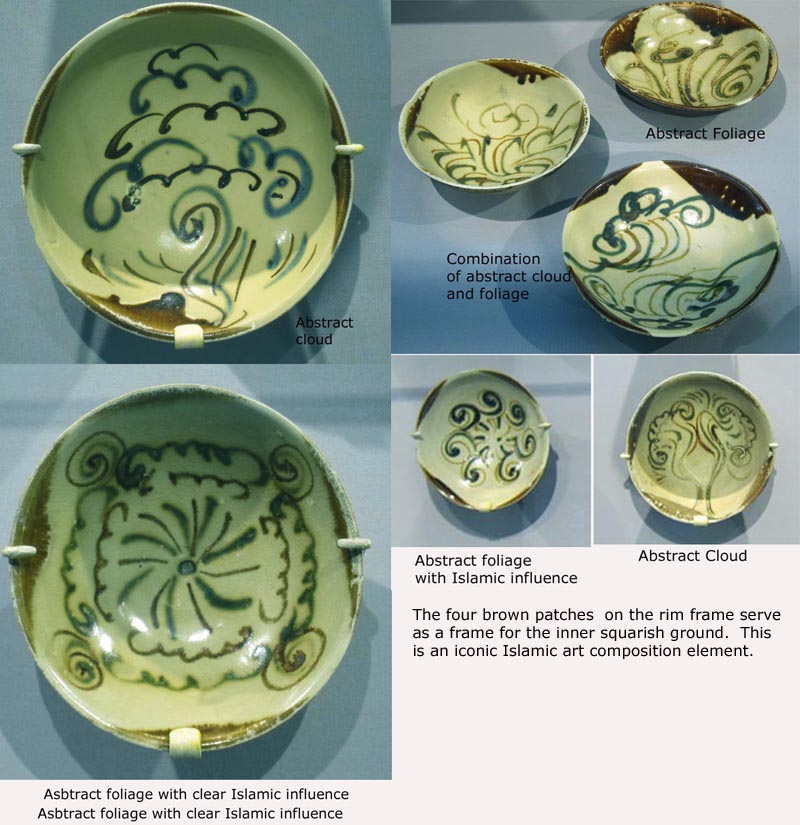

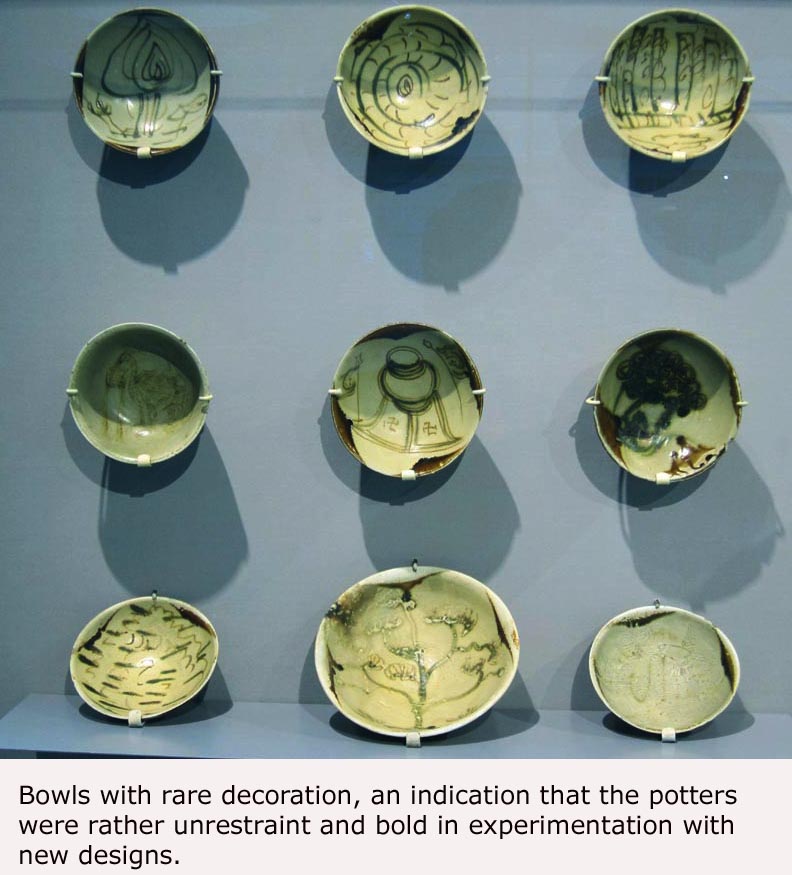

The bowls are decorated with a rich repertoire of motifs such as lotus, foliage/flower, abstract cloud, bird, calligraphic inscription, makara, corrupted arabic scripts, landscape and etc. Although a portion of the decorations could be considered "neutral" and lacking in religious symbolism, the bulk clearly showed Islamic or Buddhist influences. Islamic influenced motifs included those with a corrupted form of Arabic calligraphic scripts or palmette form of foliage. The use of Arabic calligraphic scripts was a common decorative technique in the Middle East. It is obvious that the Changsha potters did not know the scripts but copied them slavishly initially. Overtime, it was distorted and became a corrupted form which appeared more like abstract calligraphic lines. There is a vase excavated from a grave in Yangzhou. It was decorated with Arab script which has been identified by Islam scholars as the famous Arabic phrase "God is Greatest".

|

|

| An example with Arabic script . It is of Arabic origin and dated to 9th cent. Abbasid dynasty. Not from the Belitung wreck. |

Those with clearly Buddhist symbolism included lotus and the makara. Apparently, there was conscious effort to appeal the artistic sensibility of the Muslim and Buddhist consumer market. The wide variety of motifs suggested that the cargo was not dedicated to a single destination. Part of the cargo was likely targetted at the Buddhist/Hindu dominated Mataram and/or Sirvijaya Kingdom and the rest for the Muslim Abbasid empire. But from archaeological surveys, it is clear that at least a section of the consumers was more cosmopolitan in outlook. They do accept decorations of different religious symbolism. Hence, bowls with buddhist symbolism decoration were also found in Muslim dominated Middle East and vice versa.

Besides decoration of lotus, corrupted arabic inscription and palmette foliage, the other most popular motifs are the abstract cloud and abstract foliage. In fact, all the Changsha bowl decoration is painted on a square ground framed by 4 brown patches on the rim. This is an iconic Islamic composltion element. Islamic decoration tends to avoid using figurative images and frequently uses geometric patterns build on combinations of repeated overlapping and interlacing squares and circles. They may constitute the entire decoration or form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments.

Many of the above decorations clearly involved a different degree of abstraction with the motif modified and distorted beyond recognition. However, we do find some rare examples which its actual physical representation of landscape is more discernible.

More realistic representation of landscape

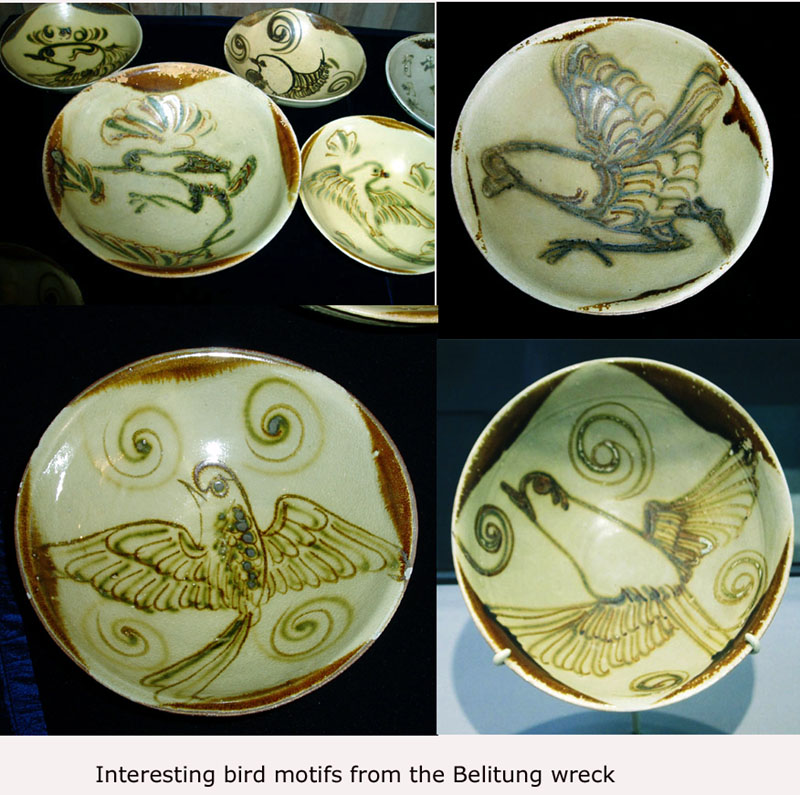

Another such category is the wide varieties of birds. Comparatively there are few and seldom found in overseas archaeological excavation. In contrast, this is a more common motif found on Changsha vessels, especially ewers, for the domestic market.

Rare example of peacock decoration

Changsha potters mainly used painting and moulding for decoration of the vessels. Incising is not foreign to them but seldom utilised probably because it was not widely appreciated by the buyers. However in the wreck we find a rare example with elaborate decoration of bird.

Rare example with incised bird motif

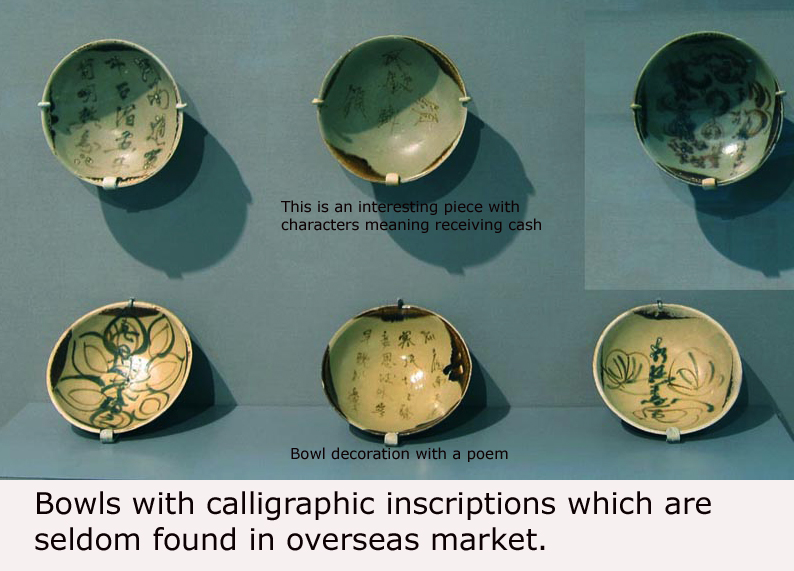

Besides the above, there are small number with calligraphic inscriptions. They are more commonly found in domestic market where its meaning is understood by the owner. The content consisted of mainly poem, maxim and idiom. However, in this wreck we also find some odd inscription such as characters meaning collect money.

In the wreck, there are couple of bowls decorated with poem written in wild running calligraphic script style of Huai Shu (怀素), a famous Tang Monk noted for his accomplishment in calligraphy. They are very rare and very few examples were known to have existed.

Bowl written in the wild runing calligraphic style (狂草书)

In the cargo, there is a small group of vessels with an opalescent bluish cast over the celadon glaze. This phenomenon is similar to that found on Jun wares of the Song/Yuan Dynasty. In view of the small number, we are not able to ascertain whether it was accidental or the potters had mastered the glaze formula to induce such effect. The glaze is still a form of celadon glaze with iron-oxide as the colorant. Under normal condition, it would resulted in green colour under reduction kiln atmostphere and more brownish under oxidation. The Jun effect can only materialised with some changes made to the glaze formula. Scientific analysis revealed that the glaze composition consisted of lower alumina ranging from around 14 to 11 %. Glaze within a range of mixture of silica, alumina, calcia and potassia induced a state termed liquid-liquid phase separation during cooling. The micro-structure showed that liquid-liquid phase separation glaze looks like caviar or frogspawn glass droplets. Through an interference effect termed Rayleigh Scattering, they scattered blue light. Hence, the bluish caste we see. It is important to understand that the colour that we see is not actual colour due to the colorant in the glaze but an optical effect.

Short video clip of the Jun-type Changsha wares can be viewed here.

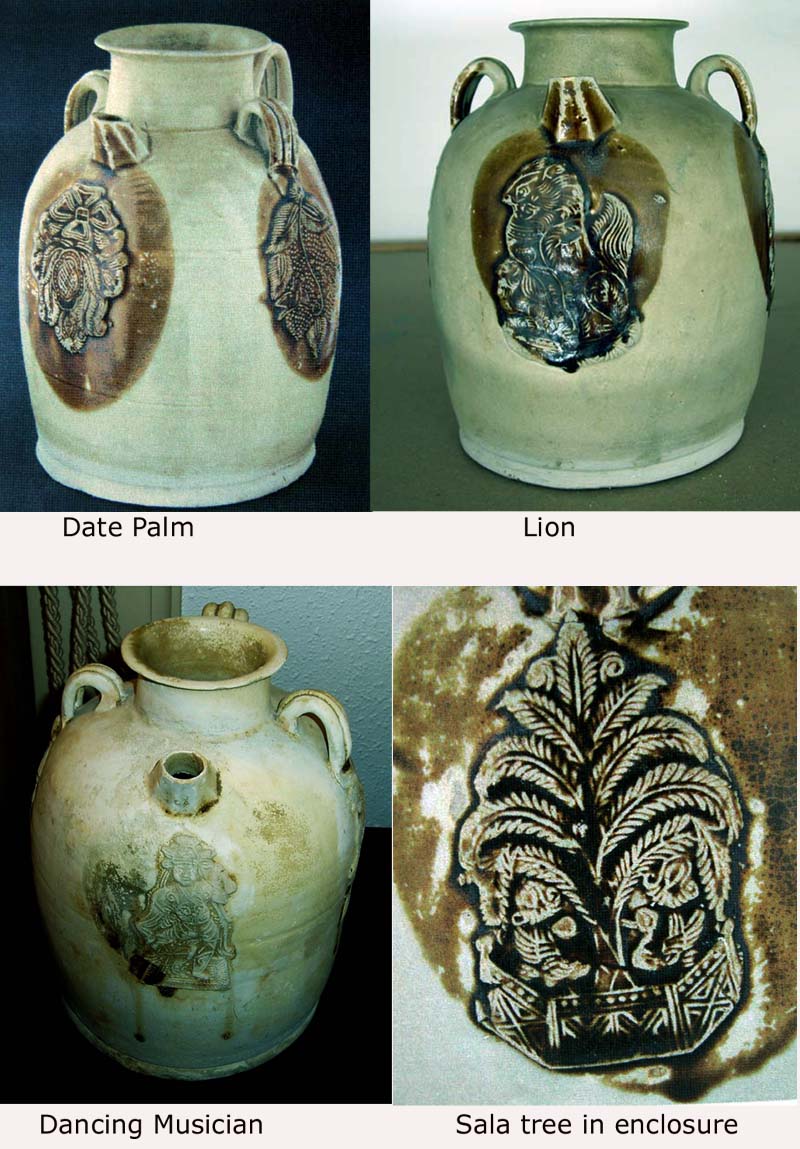

Ewers were also popular export items and some quantity were recovered from this wreck. Majority have applique embellishments such as date palm, lion, dancing musician, sala tree in enclosure and etc. The date palm medellion is clearly a very distinctive middle Eastern decorative motif. The date palm is a flowering plant species and probably originated from lands around Iran. Those with Buddhist symbolism includes lion and sala tree applique. The sala tree is native to the Indian subcontinent and has religious significance in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Buddhist tradition holds that Queen Māyā of Sakya, while en route to her grandfather's kingdom, gave birth to Gautama Buddha while grasping the branch of a sala tree in Lumbini in south Nepal. The Buddha was also said to be lying between a pair of sala trees when he passed away.

There are very few ewers with painted motif from this wreck. In the domestic market, both painted and applique decorations were favoured by the buyers.

Some other vessels form which are relatively small in number in this wreck are illustrated below.

......... Continue to Page 2