A Study of Chinese Ceramics in the Cirebon Wreck

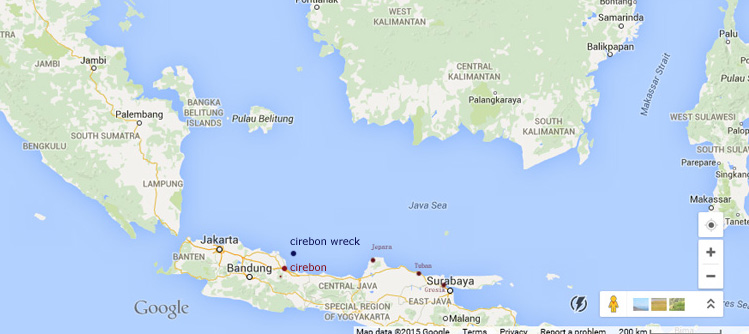

In 2003, local fishermen discovered Chinese ceramics in

their fishing nets in the Java Sea, recovered from a

shipwreck located approximately 54 meters deep and 100

kilometers off the coast of Cirebon, West Java. A

private company salvaged the wreck in 2004, recovering

around 250,000 artifacts:

-

65%: Chinese and other ceramics.

-

10%: Near Eastern and Indian glassware and gemstones.

-

Remainder: Ingots and metal implements.

The ship, identified as Indonesian-made, was likely

engaged in intra-regional trade. Scholars believe it

loaded its cargo at a Srivijaya-controlled port before

setting sail for Central or East Java. The vessel’s

substantial cargo volume suggests a thriving consumer

market in Java. Given the political dynamics of the era,

the ship was probably bound for East Java. Between the

8th and 10th centuries, the Mataram Kingdom, a

Hindu-Buddhist state in Central Java, rivaled the

Srivijaya Empire, the dominant maritime power based in

Palembang. While Mataram’s agrarian economy did not

directly challenge Srivijaya’s control over trade, by

the early 10th century, Java’s economic and demographic

center had shifted eastward to the Brantas Delta (near

modern-day Surabaya). This region developed a mixed

economy, integrating agriculture with maritime commerce.

Inscriptions from the 10th–13th centuries attest to

bustling trade networks at East Javanese ports such as

Tuban and Gresik in the Brantas Delta, alongside Jepara

on Central Java’s northern coast.

|

| Location of Cirebon Wreck |

Dating of the Chinese Ceramics and the Wreck

Key evidence suggests the wreck dates to the late 10th century:

- Lead Coins: Inscribed with "Qian Heng Zhong Bao" (乾亨重宝), first minted in 917 A.D. by the Nanhan Kingdom (Five Dynasties period).

- Yue Bowl Inscription: A cyclical date "wu chen" (戊辰) and the workshop mark "Xu Ji Shao" (徐记烧). Stylistic analysis confirms a production date of 968 A.D.

- Historical Context: The wreck likely occurred within five years of 968 A.D., during the Five Dynasties–Northern Song transition. Nanhan and Wuyue (producers of Yue ware) were absorbed into the Song Empire by 971 and 978 A.D., respectively.

|

|

| Yue bowl with inccised Wu Chen Xu Ji Shao Mark |

Analysis of the Chinese Ceramics in the Cargo

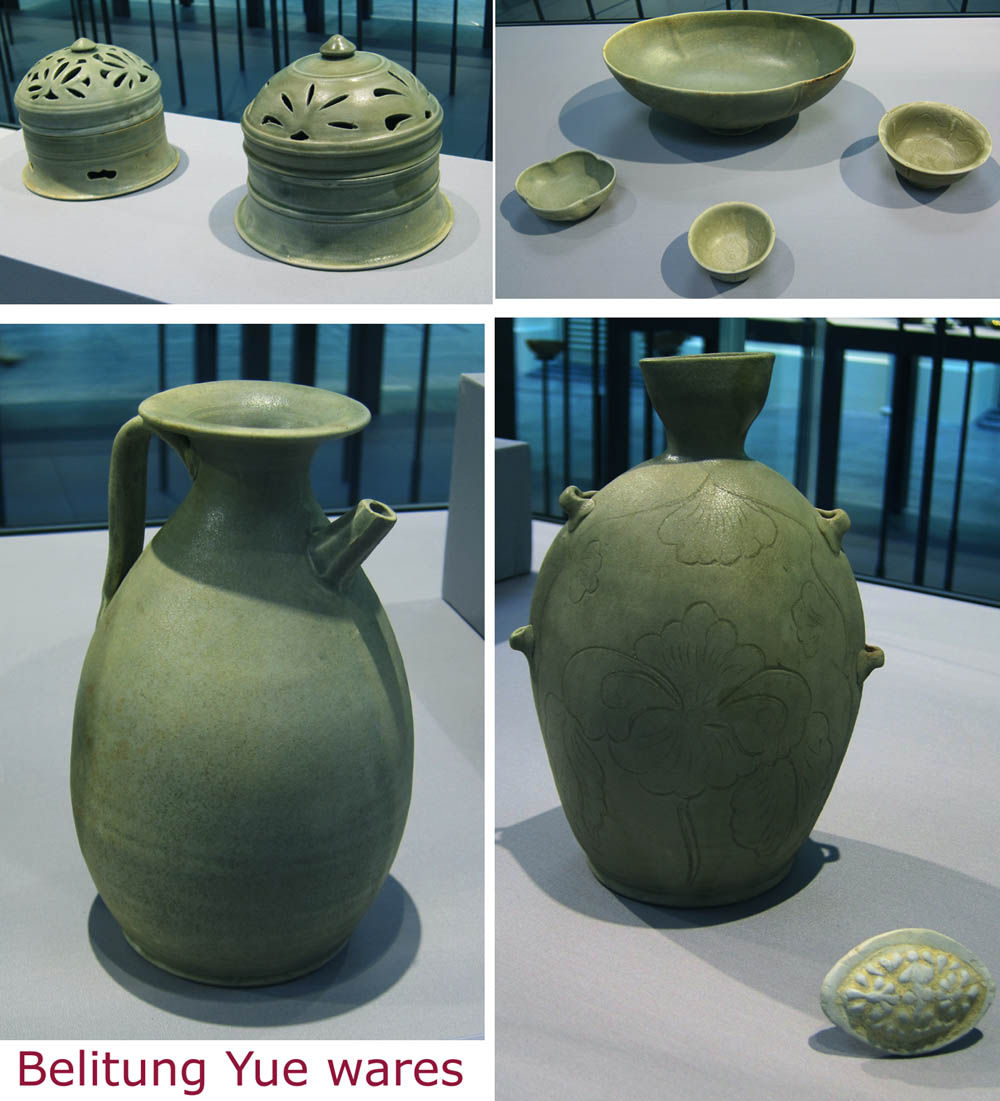

The recovered ceramics were predominantly Yue greenware, with smaller quantities of whitewares and Guangdong greenware jars and basins.

Notably absent were Changsha painted ceramics—a

prominent commodity in Tang dynasty trade and found in

9th-century shipwrecks such as the Belitung

(Indonesia), Chau Tan and Ba Ria

(Vietnam) sites. This absence suggests

that by the early 10th century, Changsha wares no longer

played a significant role in Chinese maritime trade,

aligning with archaeological evidence dating their

terminal production to the Five Dynasties Period.

Yue kilns had solidified their dominance in greenware production by this time, a status maintained into the early Northern Song period. Yue ware catered to both high-end and lower-end overseas markets, demonstrating broad commercial appeal.

Meanwhile, Xing whiteware from Hebei faced mounting competition from emerging northern kilns producing similar ceramics. By the Five Dynasties Period, its prominence had waned, and its position as the preeminent center for whiteware production was ultimately supplanted by Ding ware.

Since the Tang Dynasty, Guangdong kilns in the Pearl River Delta was the main supplier of green glazed storage jars and basins. It has maintained its position in this category without challenge.

1. Yue Greenware

Historical Background

The Yue kilns of Zhejiang had a long tradition of greenware production, dating back to the Zhou period (1046–256 BCE). Potters refined celadon during the Eastern Han (25–220 CE), and by the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), Yue ware became highly valued, especially in tea culture. The finest examples were Mise porcelain, praised in 9th-century texts.

|

| Belitung Yue wares exhibited in Singapore Asian Civilisation Museum. |

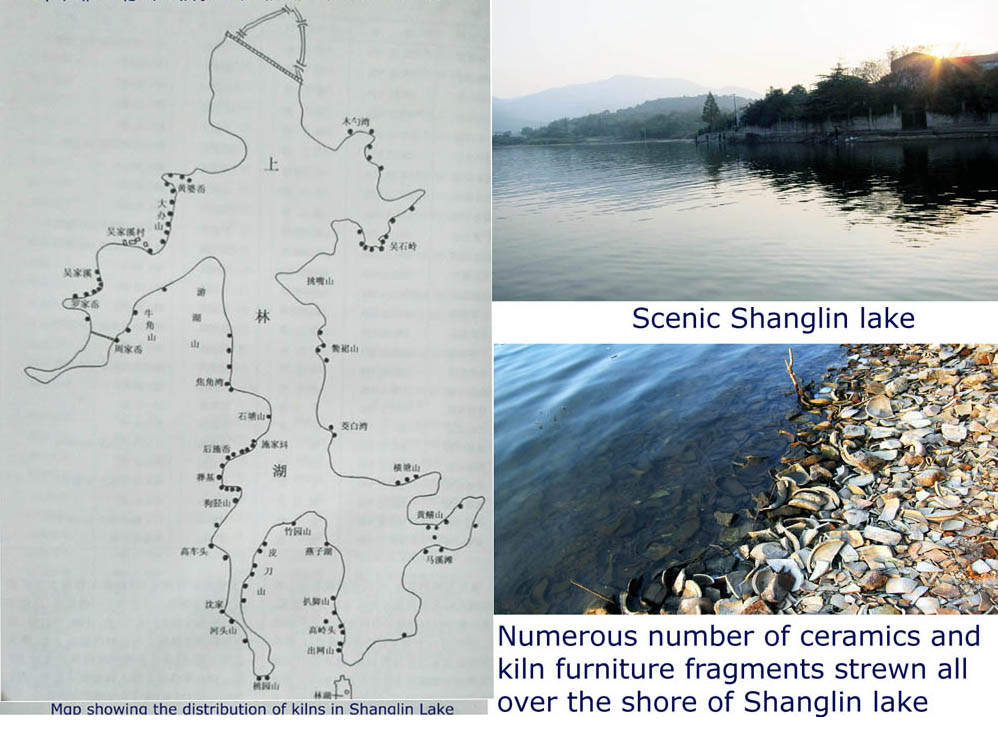

Yue ware peaked during the Five Dynasties and Northern Song (907–1127 CE) but declined afterward. The Wuyue Kingdom (907–978 CE) supported its production, leading to large-scale tribute wares and exports, with many pieces found in Southeast Asia, including the Cirebon shipwreck. Major production centers were around Shanglin Lake and Dongqian Lake, with over 80 kiln sites identified. Mingzhou (modern Ningbo) served as the primary export hub, connecting Yue ceramics to trade networks across Asia and the Indian Ocean.

|

|

| Map showing distribution of Yue kilns |

The Cirebon Cargo: A Treasure of Yue Wares

The Cirebon shipwreck cargo offers a remarkable

assemblage of Yue ceramics, highlighting the diversity

of vessel forms and decorative motifs characteristic of

the transitional Five DynastiesNorthernSong period.

Vessel Types and Decoration

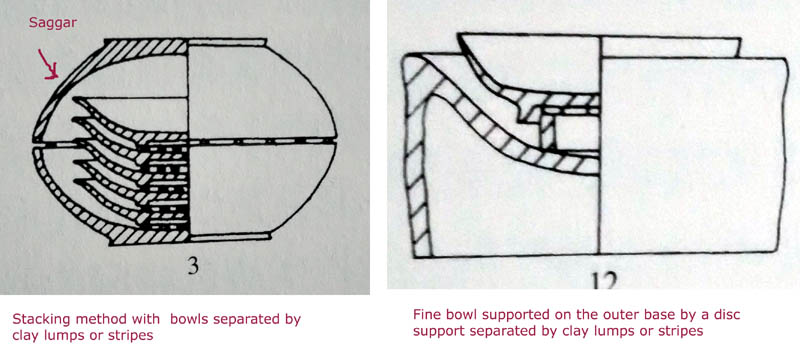

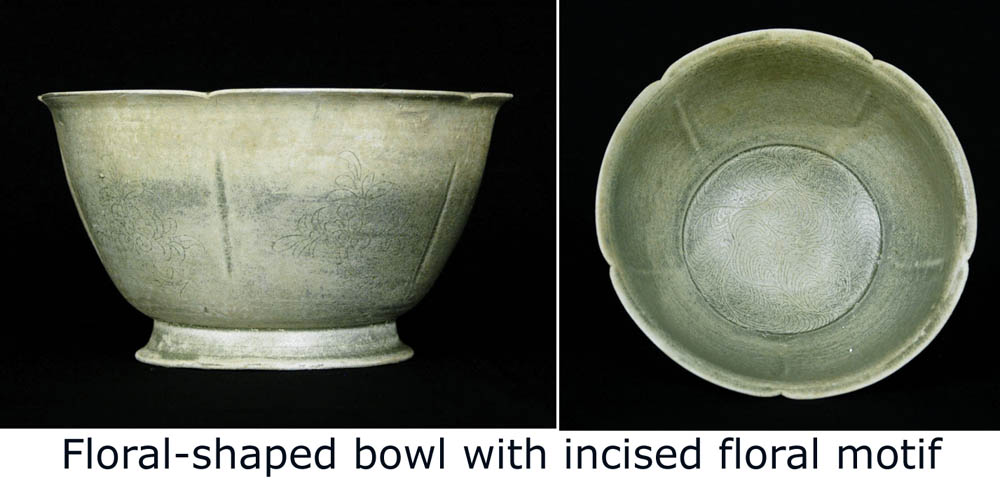

- Bowls and Dishes

Bowls and dishes dominated the cargo, primarily

comprising modest-quality wares produced for mass

consumption. These utilitarian pieces often retain

interior marks from kiln-stacking clay supports (clay

lumps or strips) and feature unglazed foot rings,

reflecting efficient kiln-packing practices.

In contrast, higher-quality bowls and dishes exhibit

fully glazed foot rings and lack interior stacking marks,

suggesting they were fired individually in *saggars*

(protective ceramic containers). While most retain

simple forms, finer examples display lobed rims, fluted

walls, and splayed feet—designs influenced by

contemporary silverware. The most distinctive decorative

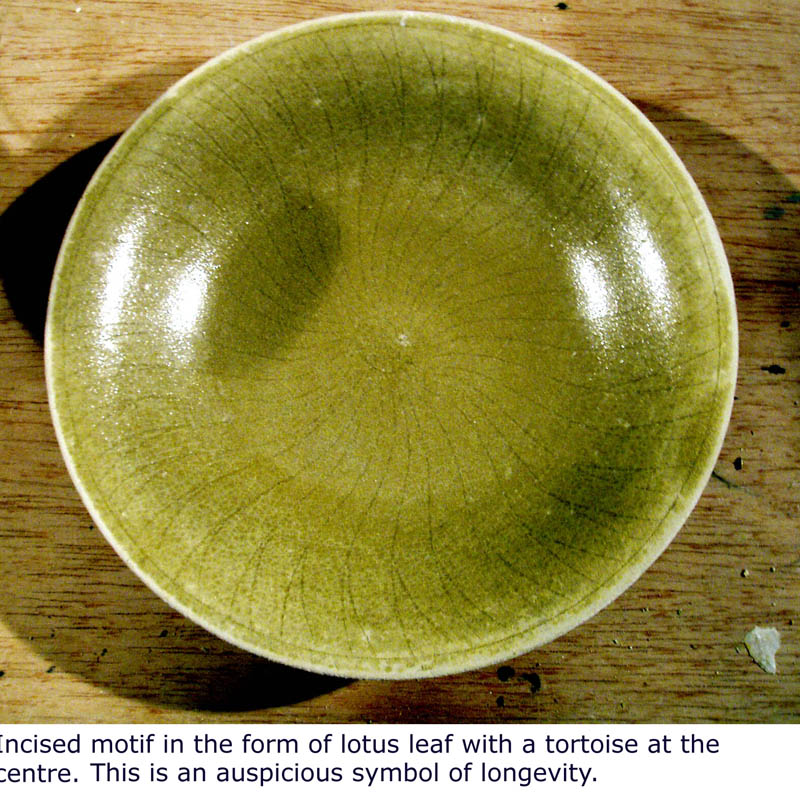

element is the carved lotus petal motif in high relief

on exterior walls, a hallmark of Five Dynasties and Song

ceramics. The finest pieces are further embellished with

intricately incised patterns.

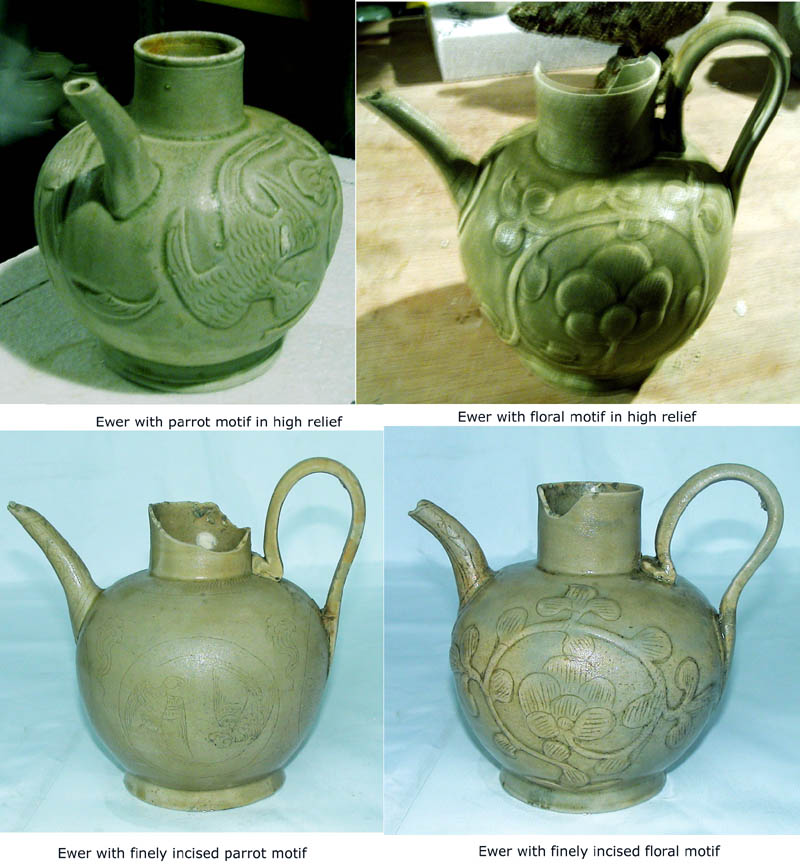

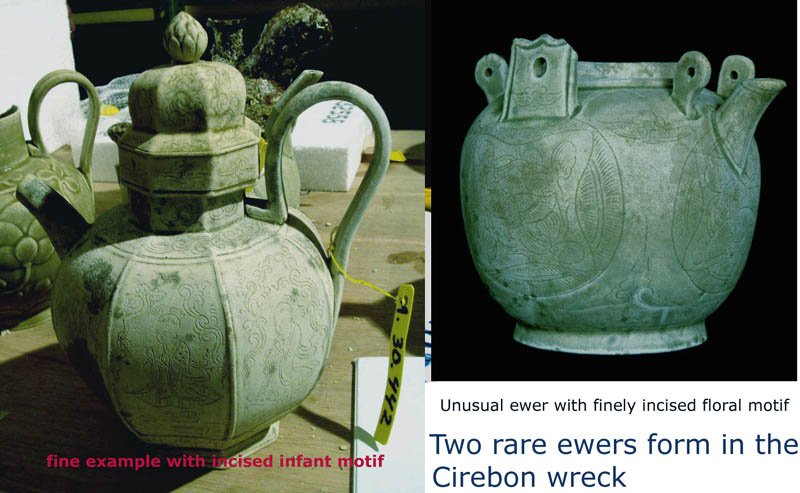

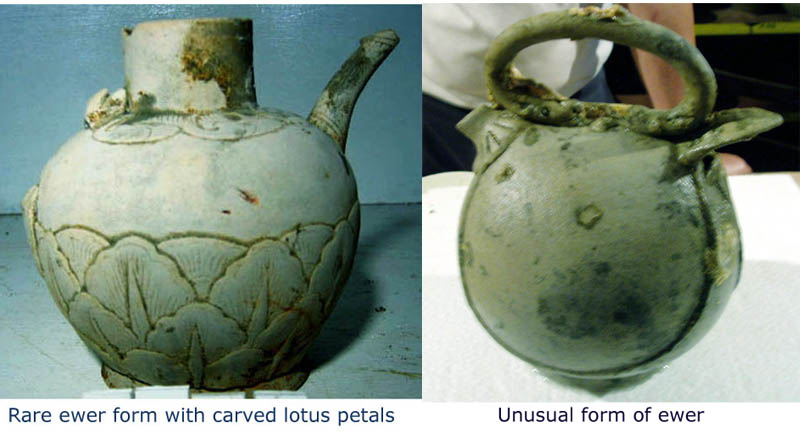

- Ewers

Ewers, another prominent category, varied in size. Most were undecorated, though luxurious versions were adorned with finely incised or carved high-relief motifs, likely intended for elite patrons.

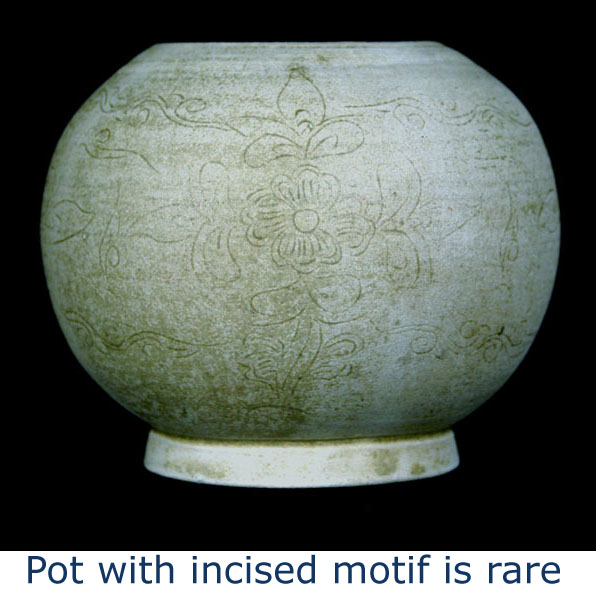

- Pots

Pots constituted a significant portion of the cargo. While many are plain or fluted, numerous examples feature the iconic carved lotus petal motif. Rare specimens display delicate incised decoration.

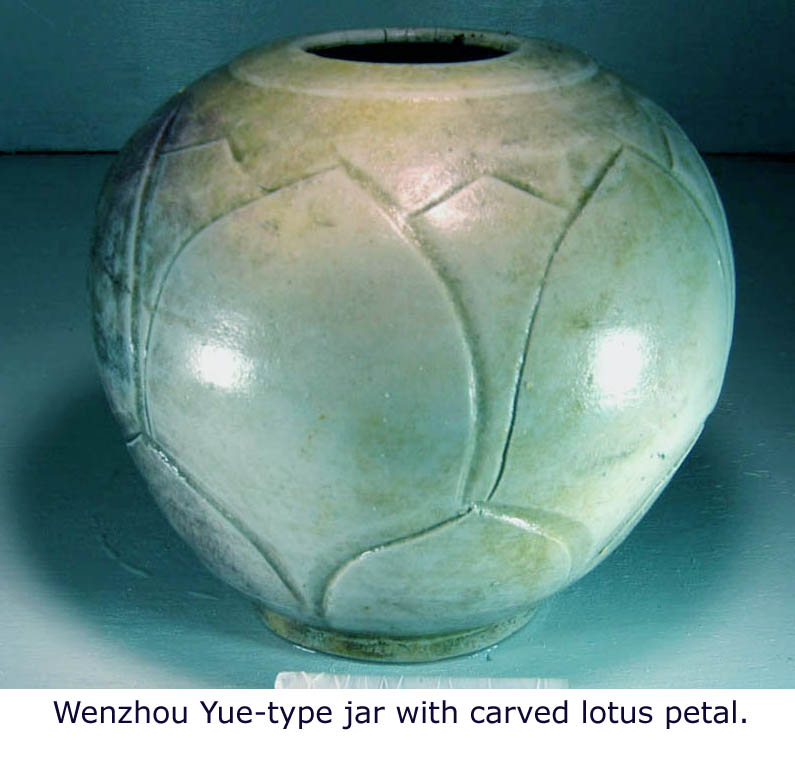

A distinct subgroup of pots exhibits a lighter green

glaze paired with bold, coarser lotus carvings. Though

likely produced at Wenzhou kilns in Zhejiang, these are

classified as “Yue-type” wares due to their stylistic

affinity with Yue traditions.

- Other Notable Forms

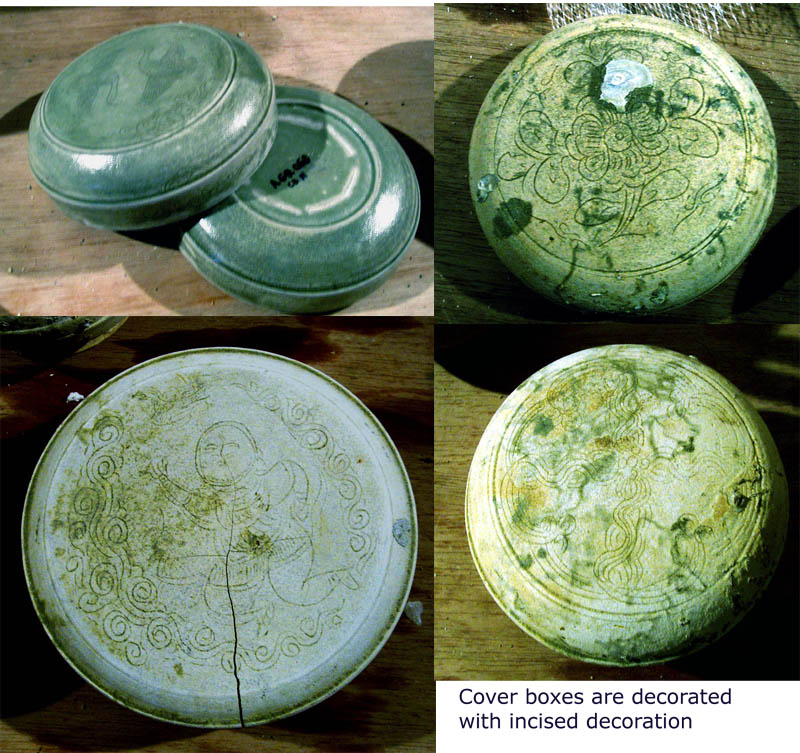

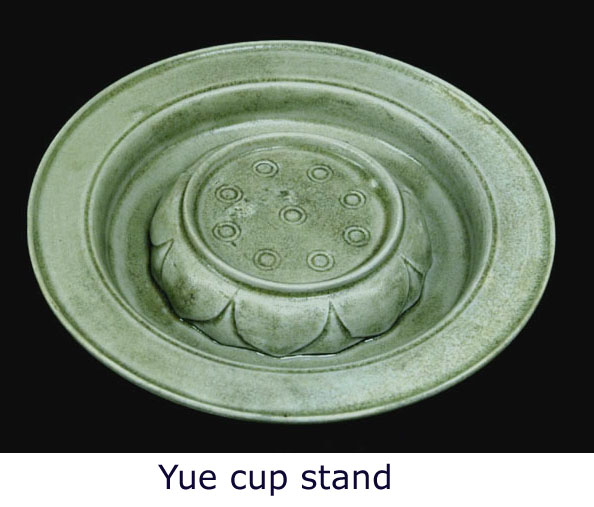

The cargo also included a small number of covered boxes,

cups, and rare objects such as a *makara*-shaped oil

lamp (a mythical aquatic creature), a multi-tiered food

tray, a cup stand, a bird whistle, and a conch.

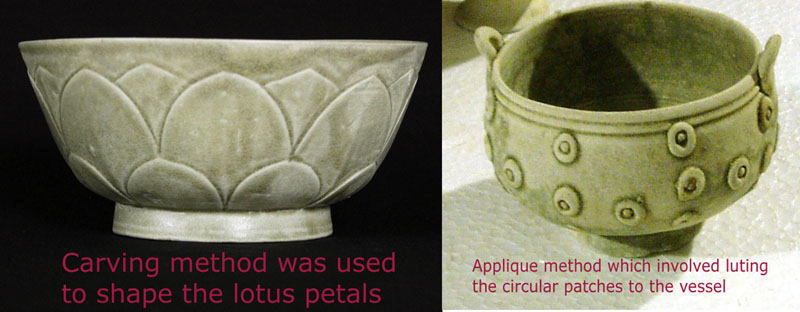

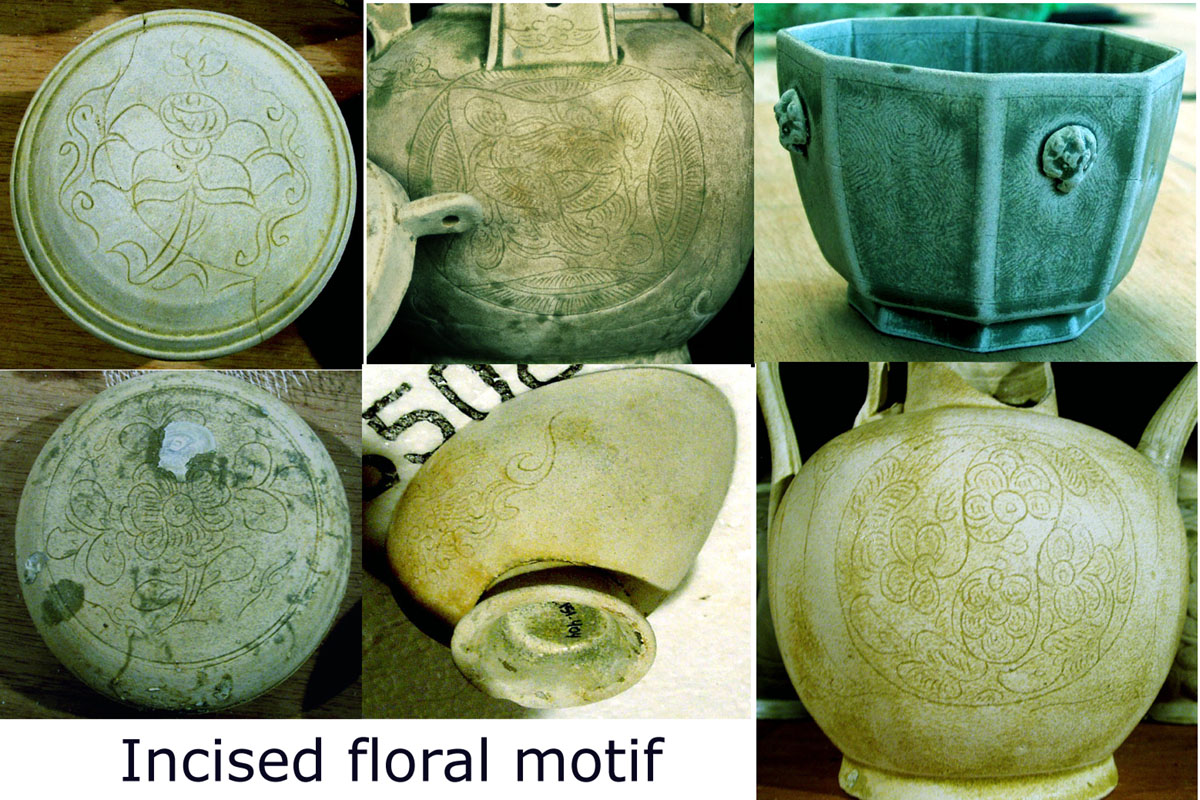

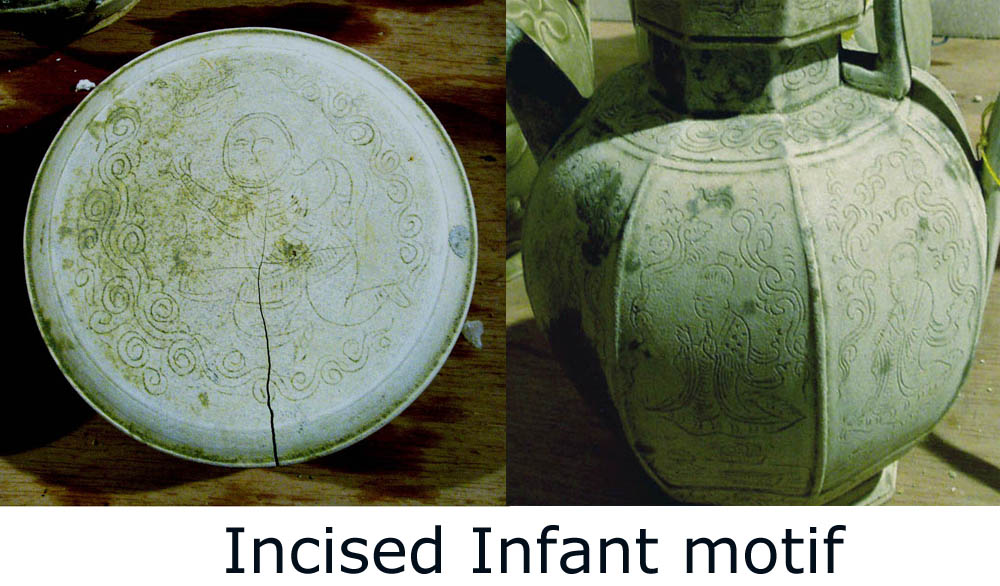

Decorative Techniques

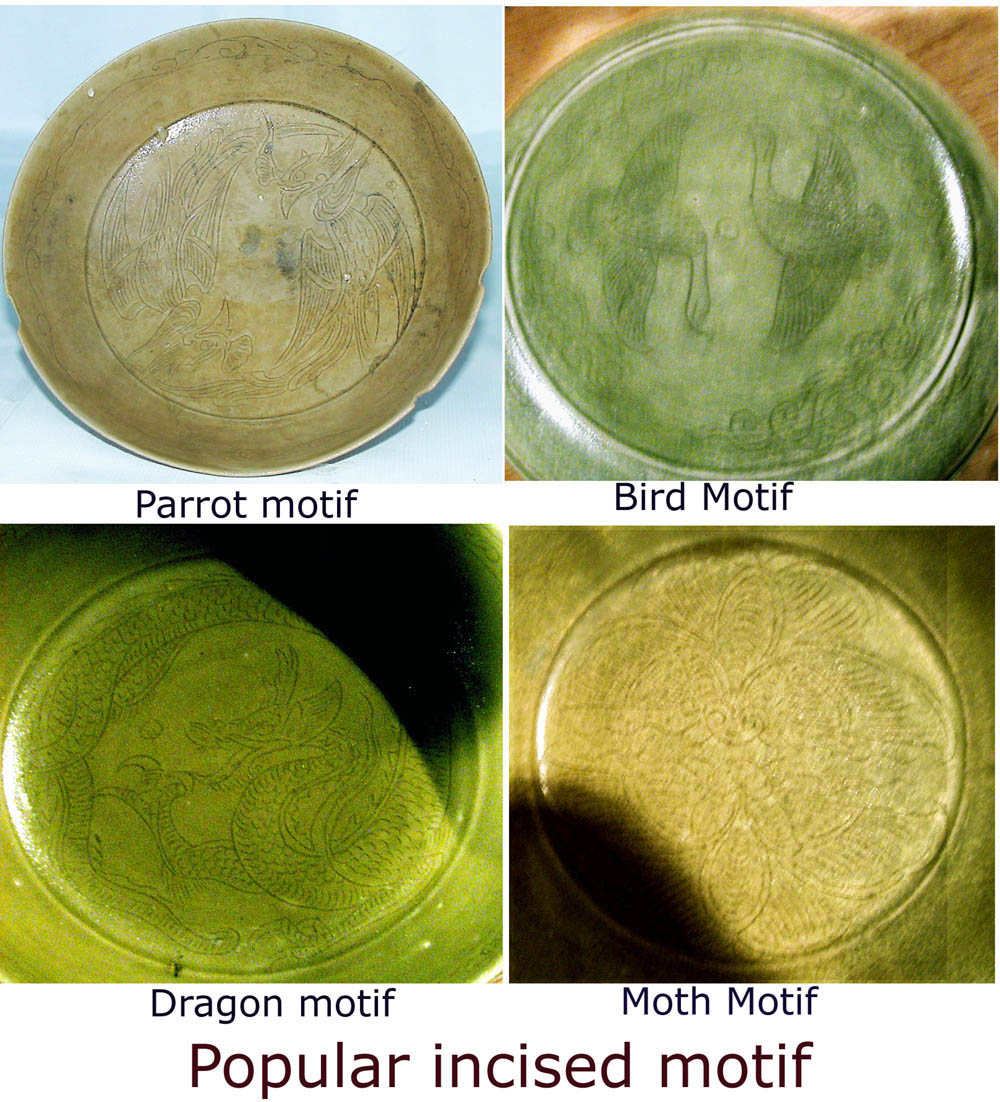

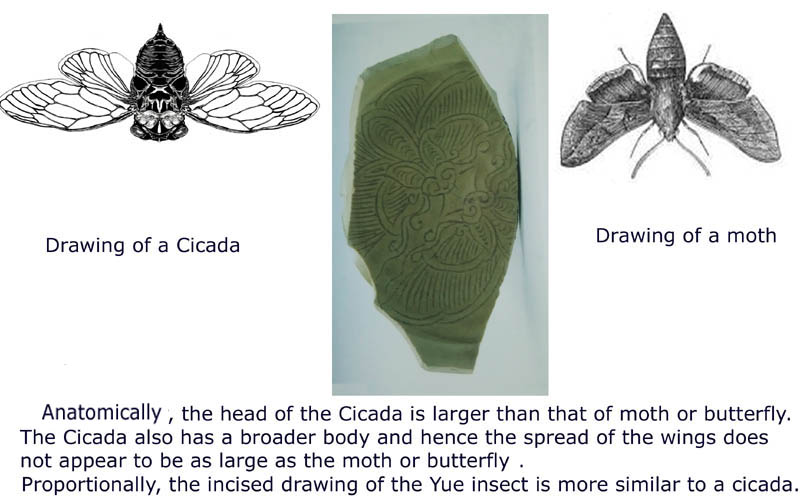

Yue artisans employed diverse decorative methods, including carving, incising, sgraffito, appliqué, molding, and openwork. Fine incising flourished from the Five Dynasties through the early Northern Song period, featuring motifs such as phoenixes, dragons, parrots, birds, cicadas, florals, and occasional human figures.

|

|

|

| Mouding method was used to shape the form of phoenix head, counch, makara, deer, bird and etc. |

|

| The cicada motif is sometimes mistaken for a moth or butterfly due to physical similarities. However, the cicada holds deep auspicious symbolism in Chinese decoration, representing transformation and resurrection. Its life cycle, involving years underground before emerging, reinforces this symbolism. In ancient Chinese rituals, jade cicadas were placed in the mouths of the deceased to signify permanence, purity, and transformation. Cicadas were also depicted in other materials like silver and inkstones, such as those found in the Belitung wreck. Given its cultural and religious significance, the cicada interpretation is the most appropriate. |

Inscriptions

Inscriptions on Yue wares are relatively common. Lin

Shimin (林士民), a leading scholar of Yue ceramics,

categorizes inscriptions from Wu Yue-period kiln sites

into 11 groups:

-

Surnames: 章, 王, 徐, 上, 大, 姜, 千, 合

-

Workshops: 项记, 阮记, 柴记

-

Chinese numerals: 一 (1) to 八 (8)

-

Locations: 上 (upper), 下 (lower), 右 (right), 左 (left)

-

Cyclical dates: 太平丁丑, 辛酉, 辛, 乙, 子, 丁

A bowl recovered from the wreck bears both a workshop mark and a cyclical date (*徐记烧戊辰*) incised on its base. The most frequent inscriptions—neatly executed characters such as 大 (*dà*, “large”) or 上 (*shàng*, “upper”)—appear on high-quality vessels. Lin posits these may denote kiln locations, with 上 potentially referencing an “upper” kiln location.

Rarer examples include a bowl inscribed with 天下太平

(*tiānxià tàipíng*, “peace under heaven”) on its

interior wall and another with crudely incised 大

characters on its base, both of relatively modest

quality.

|

| Bowl with 天下太平 inscription |

|

| Bowl with many 大 character inscription |

2. Ding White Ware

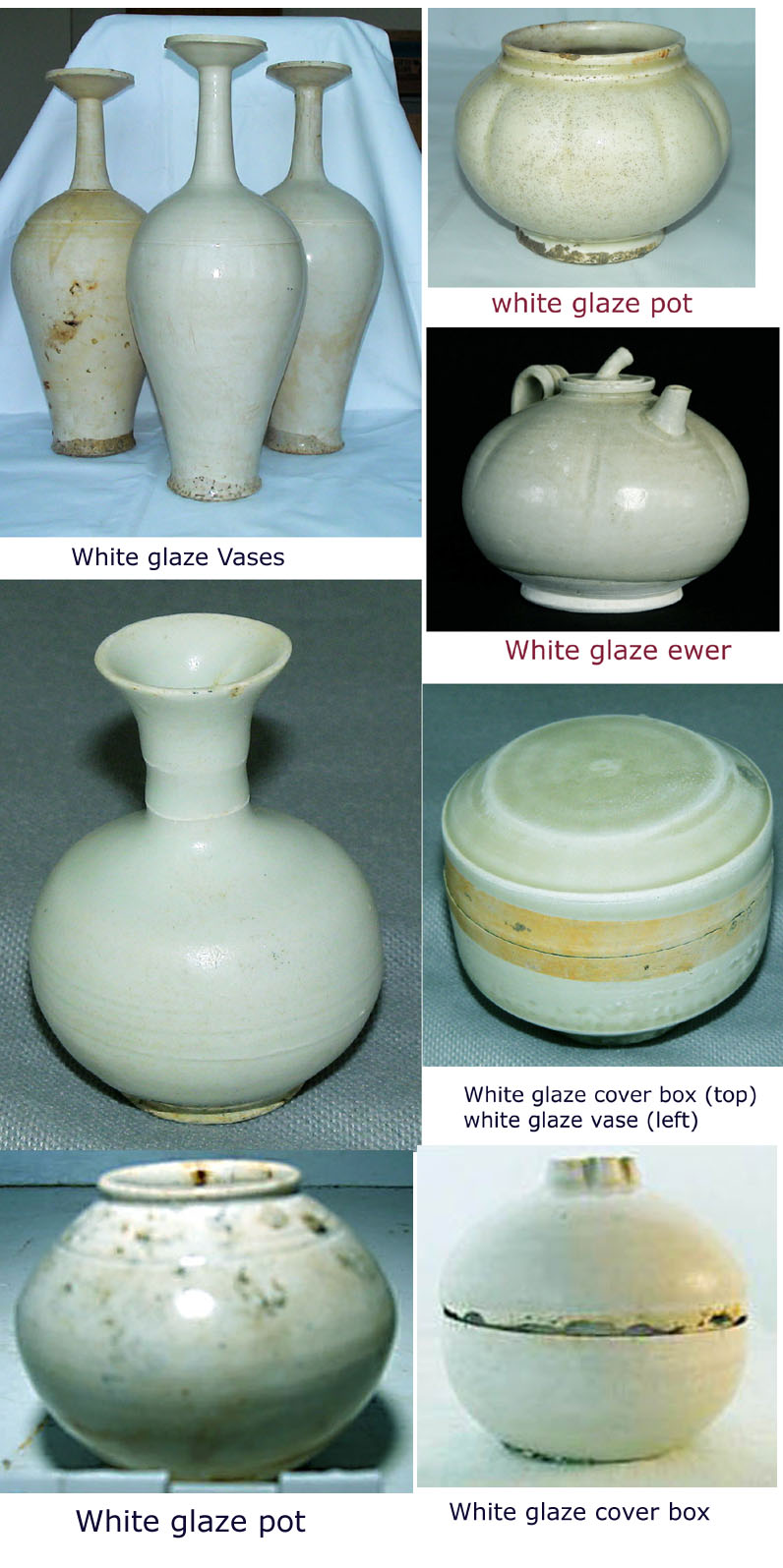

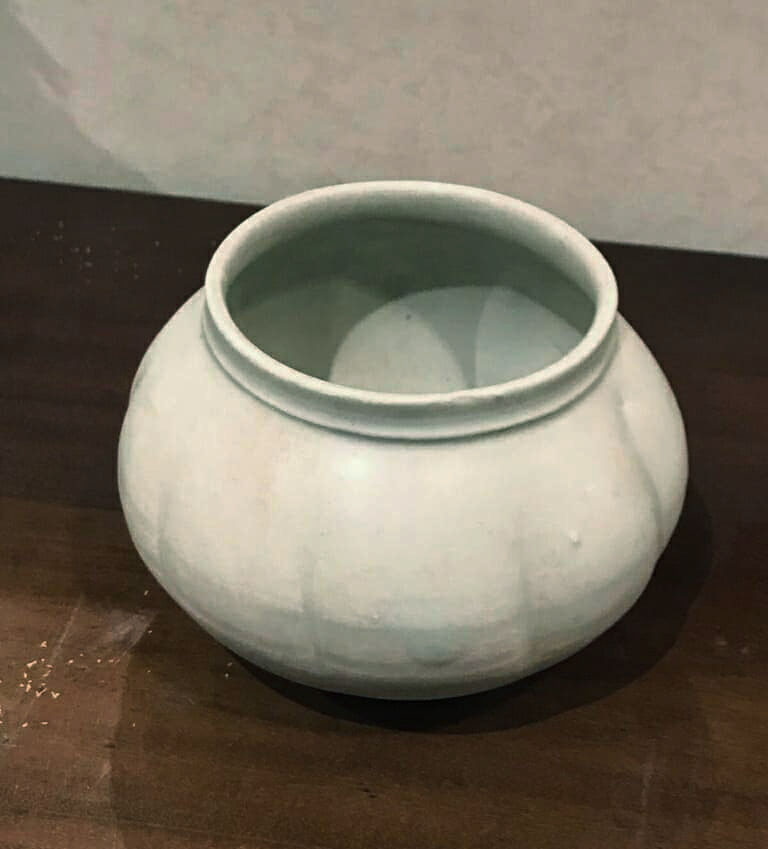

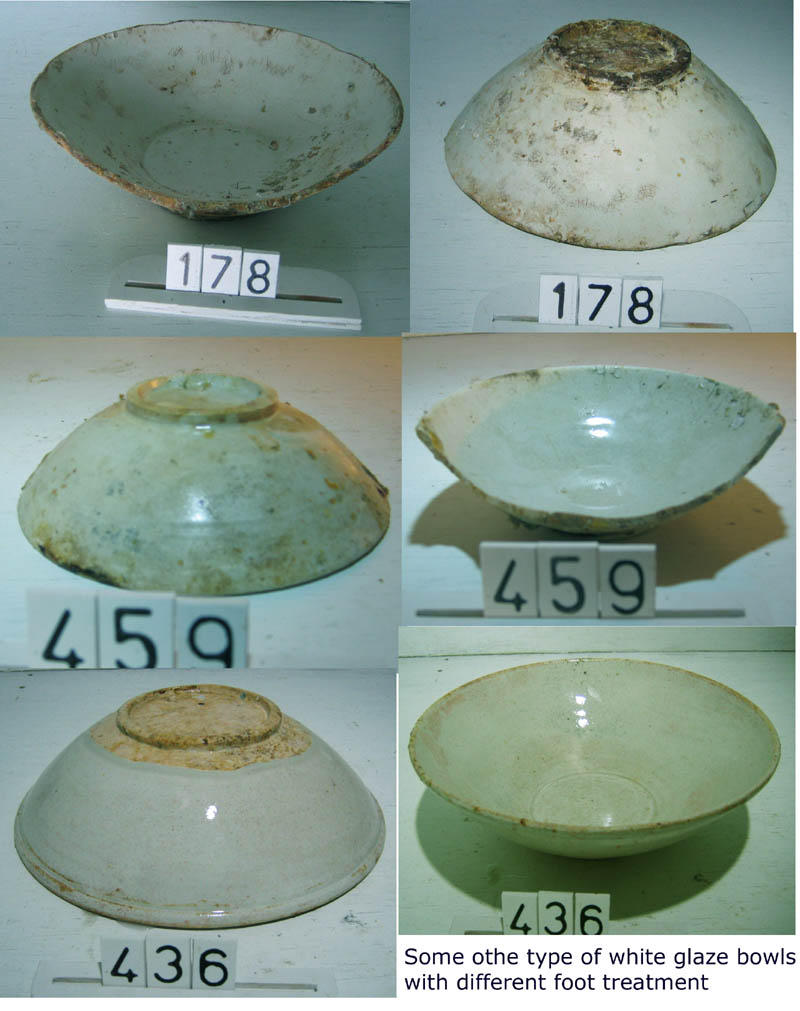

The wreck contains a significant quantity of white wares, generally identified as originating from the Ding kiln. The majority consists of bowls, while the rest includes vases, jars, ewers, covered boxes, and other items.

The wreck contains a significant quantity of white wares, generally identified as originating from the Ding kiln. The majority consists of bowls, while the rest includes vases, jars, ewers, covered boxes, and other items.

|

|

| Ding white glaze pot from the Intan wreck. This wreck carried similar cargo to the Cirebon wreck. | |

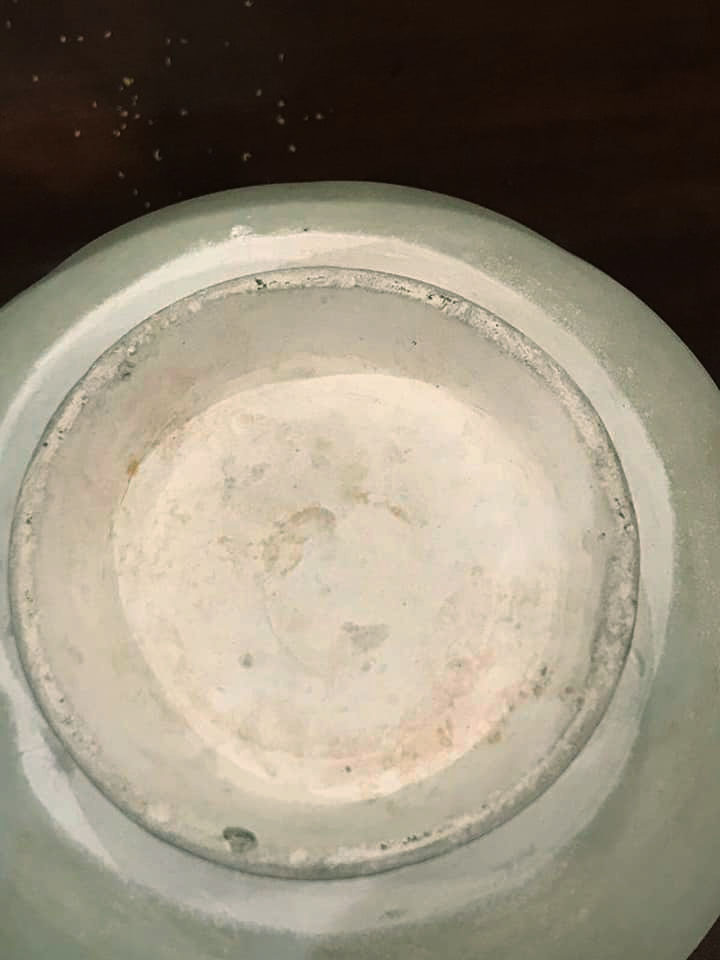

However, within Chinese academic circles, some scholars

have suggested that a substantial portion of the bowls

and dishes may have been produced at the Xuanzhou kiln

in Anhui. In 1996, archaeologists Zhang Yong (张勇) and Li

Guangning (李广宁) from Anhui attended the Annual Ancient

Ceramics Society Conference in Jianyang, Fujian. They

brought white ceramic shards excavated from the Yangong

kiln (晏公窑) in Jingxian, Anhui, sparking renewed interest

in the study of Xuanzhou white ware.

Since then, however, research progress has been limited. Few, if any, white wares have been discovered at the kiln sites, leaving insufficient information for meaningful comparisons.

Since then, however, research progress has been limited. Few, if any, white wares have been discovered at the kiln sites, leaving insufficient information for meaningful comparisons.

3. Guangdong Green Wares

Guangdong greenwares represented by large jars and

basins, were also prevalent. These were likely produced

in kilns in the Pearl River Delta, continuing a

tradition of large storage vessel production dating back

to the Tang Dynasty.

Conclusion

The Cirebon wreck provides an invaluable snapshot of

10th-century maritime trade, illustrating the economic

and cultural exchanges between China, Southeast Asia,

and the broader Indian Ocean world. The predominance of

Yue greenware underscores the dominance of Zhejiang’s

kilns in international trade, while the presence of

white wares and Guangdong greenware highlights a

diversified market. The study of these ceramics,

inscriptions, and historical contexts confirms that the

ship was likely engaged in trade between

Srivijaya-controlled ports and East Java during a

dynamic period of shifting political and economic

landscapes.

Beyond its material wealth, the wreck reveals the

intricate trade networks that connected diverse regions.

Further research will continue to refine our

understanding of the economic and artistic evolution of

Chinese ceramics and their influence on global trade

during this pivotal era.

Written by: NK Koh (28 Jan 2017), updated 21 Feb 2025

Reference: 青瓷与越窑 – 林士民