The Lena Shoal shipwreck was discovered in 1996 by fishermen off the waters of Busuanga, northern Palawan. Over 7,000 artifacts were salvaged, predominantly blue-and-white ceramics from Jingdezhen, China. Other finds included Vietnamese blue and white ceramics, a relatively small quantity of green-glazed (celadon) wares from Zhejiang Longquan, China, as well as Thailand and Myanmar, and a small number of brown-glazed jars from Vietnam and Thailand.

Analysis of the ceramics dates the wreck to the late 15th century, specifically the Ming Hongzhi period (1488–1505 A.D.).

|

| Zhejiang Longquan celadon plates |

|

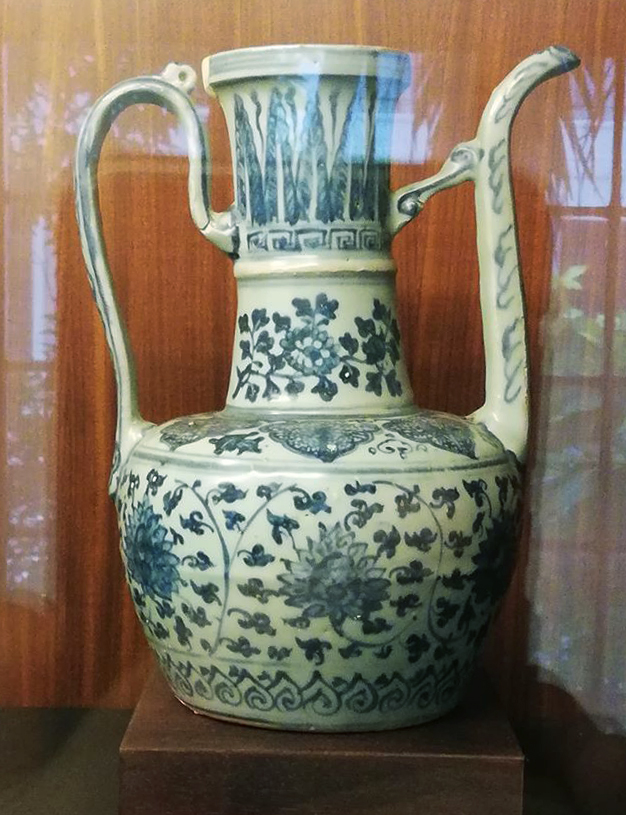

| Thai Sawankhalok green glaze jarlets |

|

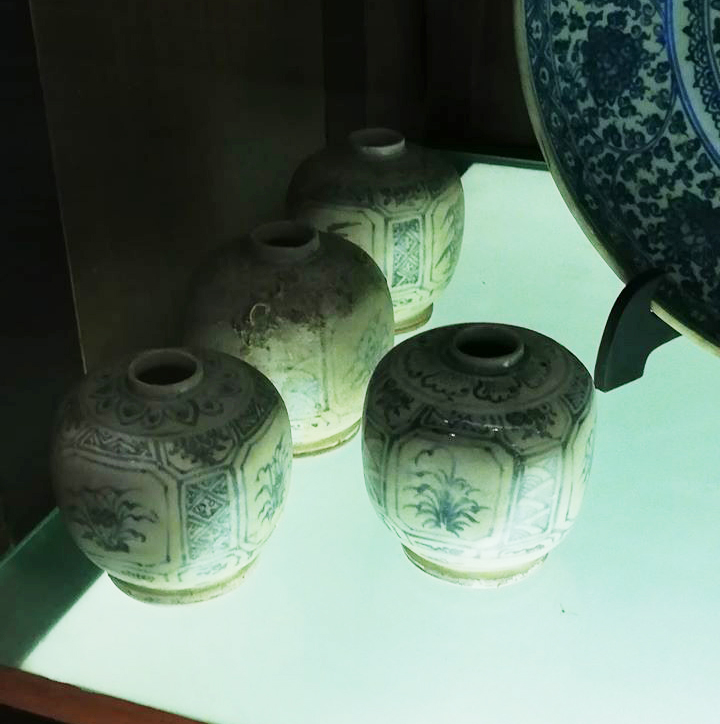

| Vietnam blue and white jarlets |

|

| Thai dark brownish glaze jar |

The vessel, approximately 24 meters long, was built in a hybrid South China Sea tradition. It featured bulkheads, a characteristic of Chinese shipbuilding, but was constructed from Southeast Asian woods using dowel joints, a technique typical of Southeast Asian shipbuilding.

Before the Ming maritime ban of 1371 A.D., this type of ship construction was unknown. It is believed that displaced Chinese merchants who had settled in Southeast Asia at that time commissioned these vessels.

During the reign of Ming Hongwu, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang imposed an imperial ban on private overseas trade. This policy aimed to curb Japanese pirate (wako) attacks along China’s southeastern coast. As a result, foreign trade was permitted only through the elaborate and highly regulated tributary system. However, by the Chenghua and Hongzhi periods (1464–1505 A.D.), the ban had become largely ineffective. Corrupt officials, wealthy landlords, and merchants operated illegal trade networks, often facilitated by overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

During Hongzhi’s reign, the court received only two official tribute missions—from Champa and Siam—through Guangzhou. Official Qiu Jun (丘浚) even appealed to lift the ban, reflecting widespread sentiment in favor of free trade. The temporary lifting of the ban during the Zhengde period (1505–1521 A.D.) further fueled trade, though later reinstatements remained ineffective.

The Lena cargo provides crucial evidence of a shift in ceramic trade dynamics. During the Ming ban, Southeast Asian kilns—particularly in Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar—filled the market gap left by China. Wrecks salvaged by Sten Sjöstrand in Malaysian waters confirm this, with key examples including:

From the late 14th to early 15th century, Vietnamese and Thai Sukhothai iron-painted wares dominated exports. Thai Sisatchanalai (Sawankhalok) kilns began producing celadon in the late 14th century, with exports peaking in the mid-15th century. Vietnamese blue-and-white ceramics became prominent by 1460–1470 A.D., with the Hoi An wreck from the late 15th century providing the best-known example.

The Lena cargo confirms a crucial transformation: Jingdezhen finally replaced Zhejiang Longquan as China’s dominant ceramic exporter. This shift marked a major change in consumer tastes. Initially introduced in the Yuan dynasty, blue-and-white ceramics were primarily intended for export. However, during the Ming period, Jingdezhen kilns gained imperial patronage, elevating blue-and-white ware to prominence.

There was a long-standing belief that production declined during the interregnum between the Zhengtong and Tianshun reigns due to the absence of reign-marked wares. However, archaeological excavations at imperial kiln sites have revealed substantial quantities of porcelain fragments from this period, proving continued production.

Under the Chenghua reign, reign marks were reintroduced, and porcelain production was extensive. Excavations and grave finds suggest that blue-and-white ceramics were not widely used among commoners until the Xuande period. Demand increased thereafter, and by the Hongzhi reign, blue-and-white ware was widely used.

Recognizing the financial burden of large-scale imperial porcelain production, Hongzhi drastically reduced orders for the palace. This forced redundant potters to turn to the domestic and export markets, improving the quality and output of non-imperial ceramics.

The Lena cargo provides valuable insight into late 15th-century mid-Ming Hongzhi Jingdezhen blue-and-white ceramics. Differences can be observed between wares produced for domestic and overseas markets.

|

| Plate with central deer/pine tree decoration encircled by floral scroll fully occupying the rest of the interior. |

|

| Plate with deer and pine tree decoration encircled by a sparse floral scroll. A more Chinese taste composition which were also used in domestic market. |

|

| One of the most impressive plate with rare decoration of mystical animal |

|

| Plate with floral scrolls decoration |

|

|

Plate with rare central decoration of pot of flower in garden setting

|

| Plate with floral scrolls design |

|

| Plate with central lotus decoration encircled by a band of alternating cloud and lotus like plant |

|

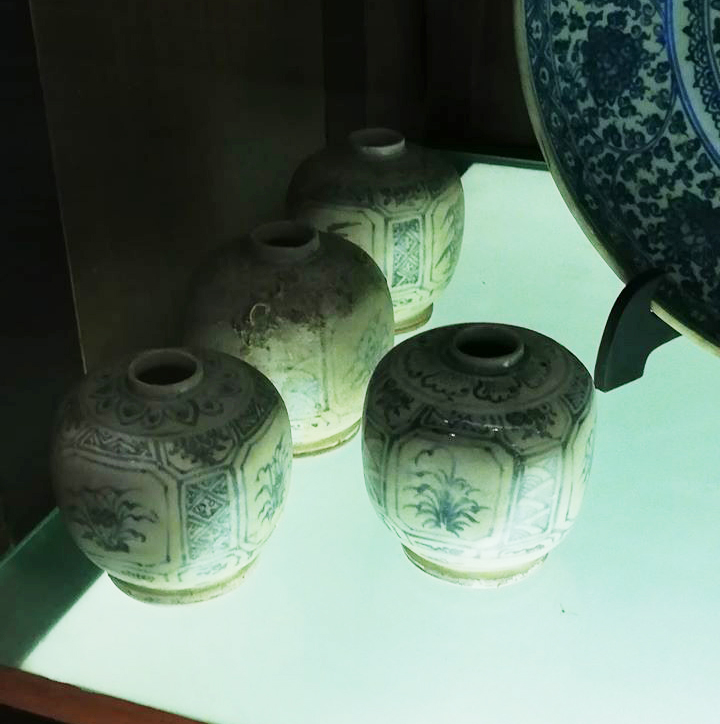

| Plate with motif in lobbed medallions |

|

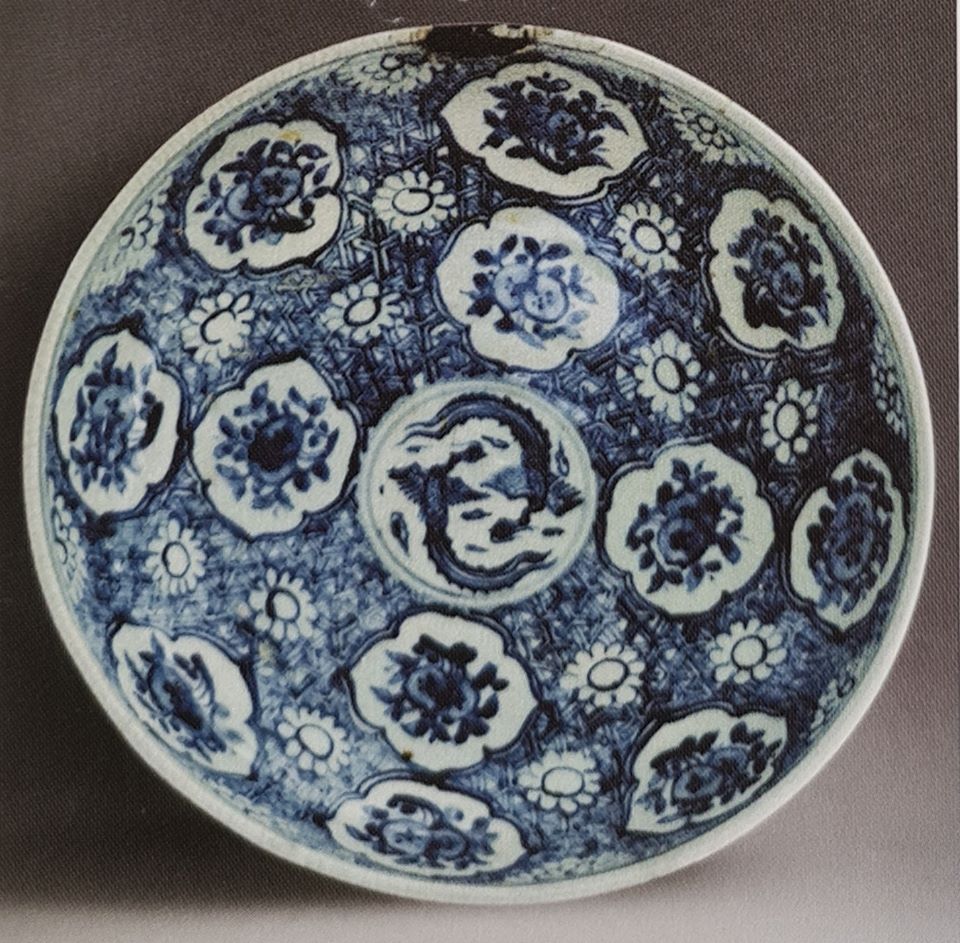

| Ewer decoration with floral scrolls |

|

|

| Water droppers shaped in the form of two ducks |

|

| Elongated cover box |

|

| Another cover boxes with floral decoration |

|

| Kendi with missing spout |

|

| Bowl with well-drawn floral decoration |

|

| Small cover box with cover missing |

|

| Small jarlets with cover |

|

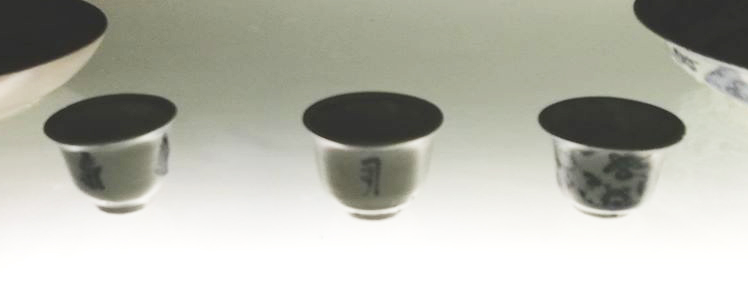

| Small cups,2 with sanskrit character, 1 floral decoration |

The Lena Shoal shipwreck provides valuable evidence of trade ceramics at a pivotal moment in history. By the late 15th century, Jingdezhen blue-and-white ware had emerged as the dominant ceramic type, marking the triumphant return of Chinese ceramics to the global market. From this point forward, Jingdezhen remained the leading supplier of export ceramics for the next 400 years.