Shufu (Luan Bai) Wares

The Yingqing (Qingbai) glaze was first introduced during the Five Dynasties period, gaining popularity in the Song dynasty and continuing into the Yuan dynasty. This glaze contains a high proportion of glaze ash, which is rich in calcium and magnesium oxides—both serving as fluxing agents that lower the glaze’s melting temperature. As a result, Yingqing glaze has low viscosity and requires a thin application to prevent overflowing. Due to minimal unmelted quartz particles, the glaze appears transparent with a clear, light bluish tone.

During the Yuan dynasty, a new glaze type emerged, reducing the glaze ash proportion from about 30% (in Yingqing glaze) to around 10%. This adjustment increased the glaze's viscosity, allowing for a thicker application. The lower flux content also led to more unmelted quartz particles and undissolved fine silica, which scattered light, giving the glaze an opaque and matte appearance. The resulting softer white or white/light bluish color tone was described as Luan Bai (卵白), meaning "goose egg white."

Most vessels using this glaze—mainly bowls and dishes—were produced at the Hutian kilns, located on the outskirts of Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. Many featured molded relief motifs, and some were inscribed with the characters Shufu (枢府), meaning "Privy Council," leading to the term Shufu wares. Other inscriptions included "Tai Xi" (太禧) ("Great Happiness") and "Fu Lu" (福禄) ("Good Fortune and Emolument"), though most pieces had either plain surfaces or molded floral, dragon, or phoenix motifs. These vessels were typically thickly potted, with noticeable glaze pooling at the inner and outer mouth rims.

|

|

.jpg) |

|

| Some examlples of Shufu wares | |

Production and Dating of Shufu Wares

The exact starting date for Shufu ware production remains uncertain. However, some examples were found in the Sinan wreck (c. 1325 AD). Additionally, pieces with the "Tai Xi" inscription were likely made for the Taixi Zongyin Yuan (太禧宗禋院), an imperial institution established in 1328 AD, suggesting production began at least after this date.

Shufu bowls and dishes are characterized by their thicker potting, thick square-cut foot rings, and distinctive glaze pooling on the outer rim. Compared to Yuan Qingbai wares, Shufu wares exhibit more matte surfaces and a grayish-white tone with a bluish tinge, while Qingbai glazes are clearer, deeper blue, and more transparent. Some Shufu wares, like the dish in the upper right of the comparison set, appear more bluish but remain distinguishable due to their matte finish.

Shufu wares were still produced during the Ming Hongwu period (1368–1398 AD). The glaze was later refined into the Tianbai (甜白, "Sweet White") glaze during the Yongle period (1403–1424 AD), known for its smooth, sugary-white finish.

|

|

| Group of Shufu dishes with moulded decoration from a wreck in Indonesian seawaters. |

|

|

| Shufu bowls and dishes are more thickly potted, featuring a thick, square-cut foot. In many pieces, the glaze distinctly pools along the outer rim. |

|

|

| Yuan Qingbai and Shufu glaze exhibit distinct differences in color and texture, as seen in the examples above. The Yuan Qingbai ewer has a deeper, more transparent blue hue, while the other two pieces are Shufu wares, both featuring a more matte glaze. Most Shufu-glazed vessels typically have a grayish-white tone with a hint of blue. However, there are exceptions, such as the dish in the upper right. Although it appears unusually bluish, it can still be distinguished from Qingbai by its matte glaze. |

|

|

|

|

|

A Shufu dish and bowl from the Ming Hongwu period, recovered from a shipwreck near Vietnam. The unglazed outer base exhibits characteristic black specks. The foot is notably thinner, and the inner wall slants outward |

Shufu Wares from Indonesian Shipwrecks

Recent discoveries from shipwrecks near Java, Indonesia, revealed a variety of Shufu wares, displaying different glaze tones—ranging from sugary white to grayish-white with a bluish tinge. The degree of glaze matteness and transparency varies, likely due to differences in firing temperatures.

|

|

| Examples from a wreck in Indonesian seawaters. The glaze exhibits variations in color and transparency due to differences in firing temperature. |

One particular dish from the wreck exhibits a thinner, more transparent glaze, revealing impurities in the body. This suggests it may have been an unsuccessful Shufu piece, as the potters aimed for a thicker, matte glaze—typical of well-made Shufu wares. Nigel Wood, in his book Chinese Glazes, noted that Shufu porcelains were made from albite-rich body stone mixed with kaolin, but had higher titania content than earlier Qingbai wares. The semi-opaque Shufu glaze may have been developed to mask these impurities.

|

| The glaze of this Shufu dish is more transparent, exposing the impurity in the body |

Shufu Glaze and Yuan Blue-and-White Porcelain

Early Yuan blue-and-white porcelain used a glaze similar to Shufu wares. However, later Yuan blue-and-white pieces saw an increase in glaze ash content, reaching a composition between Shufu and Qingbai glazes. This adjustment created a more transparent, clear-toned glaze. The ash content could not match that of Yingqing glaze, as its low viscosity would have caused excessive glaze flow, blurring cobalt-painted motifs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comparison of the Glaze in Shufu, Qingbai, and Blue-and-White Ceramics. The glaze of Yuan blue-and-white ceramics exhibits a much wider range of blue tones compared to Shufu and Qingbai wares. |

Decorated Shufu Wares

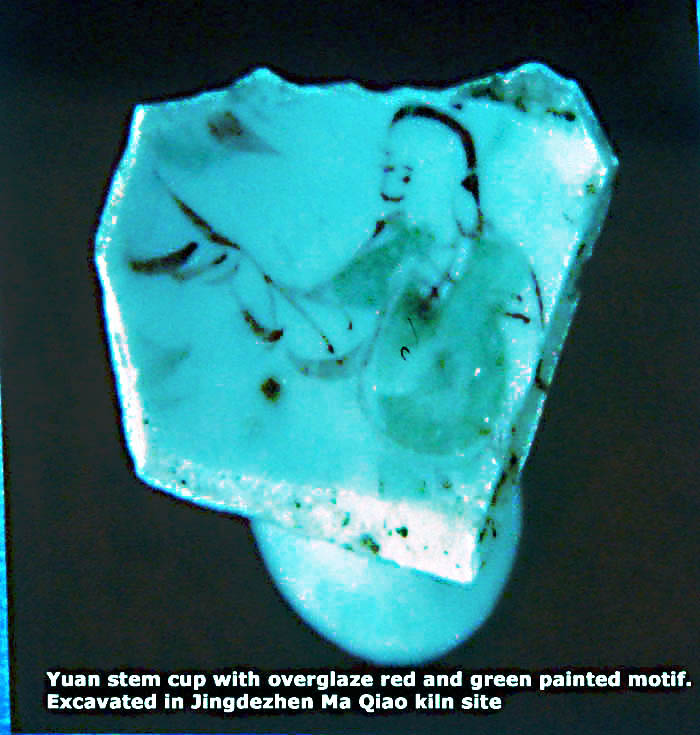

Some Shufu wares were decorated with overglaze red and green motifs, possibly inspired by Jin/Yuan-period Cizhou wares.

|

|

| Jin Cizhou bowl with overglaze red and green decoration |

Rare Wucai and Gold-Inlaid Shufu Wares

A remarkable Yuan dynasty Shufu bowl with overglaze decoration inlaid with gold was auctioned by Beijing Hanhai Auction House in 2014 for $11.2 million USD. The decorative style, referred to as "五彩戗金瓷" (Wucai Qiangjin Ci, "Five-Color Gold-Inlaid Porcelain"), involves outlining motifs with colored glaze and further inlaying them with gold.

|

| Yuan Shufu bowl with overglaze wucai gold inlaid decoration auctioned by Beijing Hanhai Auction House |

The Ge Gu Yao Lun (格古要论), a Ming dynasty text written in 1388 AD by Cao Zhao (曹昭), described Yuan Raozhou (now Jingdezhen) wares as follows:

"Pieces made in the Yuan dynasty, with small feet, impressed patterns, and bearing the mark 'Shufu', are of a very high order. New pieces, however, have large feet. Among them, the plain pieces lack unctuousness, and the blue-and-white and multicolored (五色花) specimens are vulgar in taste." (Translation by Sir Percival David)

Initially, scholars associated "multicolored" (五色花) with overglaze red and green decorations. However, in 1992, two Shufu wares with gold-inlaid decoration were found in a Yuan hoard in Ulanhot, Inner Mongolia. One of these—a stem cup—is now on loan at the Shanghai Museum.

|

| Stem cup found from a hoard in Ulanhot in 1992 |

In 1999, the Shanghai Museum acquired six additional pieces of this rare category from Hong Kong for 10 million HKD. The collection includes a saucer, bowl, Yuhuchun vase, censer, and two stem cups.

|

|

|

|

| Rare Shufu bowl and dish (in Shanghai Museum) with overglaze wucai gold-inlaid decoration |

Only a few other known examples exist:

- A stem cup with floral decoration, discovered in 1995 by Beijing Palace Museum ceramic expert Feng Xian Min at an antique market.

- A damaged Yuhuchun vase in a private collection.

|

|

Stem cup found

by the Beijing Palace Museum Ceramic expert Feng Xian Min in 1995 in

Beijing antique market |

|

|

| Yuan Yuhuchun Vase from a private collection |

Possible Influence from Minakari Enameling

This unique gold-inlaid relief style might have been influenced by Minakari—a Persian enameling technique introduced by Iranian craftsmen during the Sasanian era and later spread by the Mongols. Minakari involves fusing glass-like coatings onto metal surfaces in intricate designs, a technique that may have inspired Yuan potters.

|

|

|

In lacquerware, a similar method called Qiangjin (戗金) involves incising designs and filling them with gold. However, detailed examination of the auctioned Shufu bowl found no incision marks beneath the gold or colored glaze, suggesting the technique used was actually Lifen Tiejin (沥粉帖金), a gelled patterning and gilding method similar to mural decoration in Chinese painting.

|

|

| A mural painting featuring human figures adorned with elaborate headdresses and ornamentation, enhanced through gelled patterning and gilding techniques. |

Shufu Wares with Iron-Brown Painted Decoration

The Sinan wreck (1975, Jeollanam-do Province, South Korea) contained a few rare Shufu dishes with iron-brown painted motifs. These are exceptionally rare, with few surviving museum examples.

.jpg) |

|

| Two examples of Shufu glaze dishes from the Sinan wreck with iron-brown painted decoration |

Conclusion

Shufu wares represent an important transition in Chinese ceramics, bridging Qingbai, early blue-and-white, and later Tianbai porcelains. Their technical innovations, decorative variations, and connections to foreign artistic influences highlight their significance in Yuan dynasty ceramic history.

Written by: NK Koh

(28 Feb 2008, Updated: 27 Dec 2018, Updated: 18 Feb 2021), updated: 1 Mar 2025