Historical Background of South Sulawesi

South Sulawesi was home to several small states, primarily inhabited by two closely related ethnic groups: the Makassarese and the Bugis. Much of the region’s early history is preserved in local texts dating to the 13th and 14th centuries. South Sulawesi was a source of valuable trade commodities, including gold and spices such as nutmeg and cloves, which were imported from the nearby Maluku (Spice Islands).

By the 16th century, Makassar had become Sulawesi’s principal port and the center of the powerful Gowa and Tallo sultanates. The Makassarese rulers adopted a policy of free trade, allowing merchants from across Asia to do business. When the Portuguese reached Sulawesi in 1511, they found Makassar to be a thriving, cosmopolitan entrepôt where traders from China, Arabia, India, Siam, Java, and the Malay world converged.

In 1605, the king of Gowa converted to Islam, and between 1608 and 1611, the new faith was spread across the Bugis-Makassarese region through a series of military campaigns.

Although by the 17th century the Dutch East India Company (VOC) controlled much of the spice trade, Makassar remained a formidable competitor. The Dutch launched several military campaigns during the first half of the century but failed to capture the city. Eventually, they allied with the Bugis leader Arung Palakka and defeated Sultan Hasanuddin of Gowa in 1669. Foreign and indigenous traders were expelled from Makassar. Although the city continued to participate in regional trade as part of the VOC’s trading network, it never fully regained its former stature as a major entrepôt.

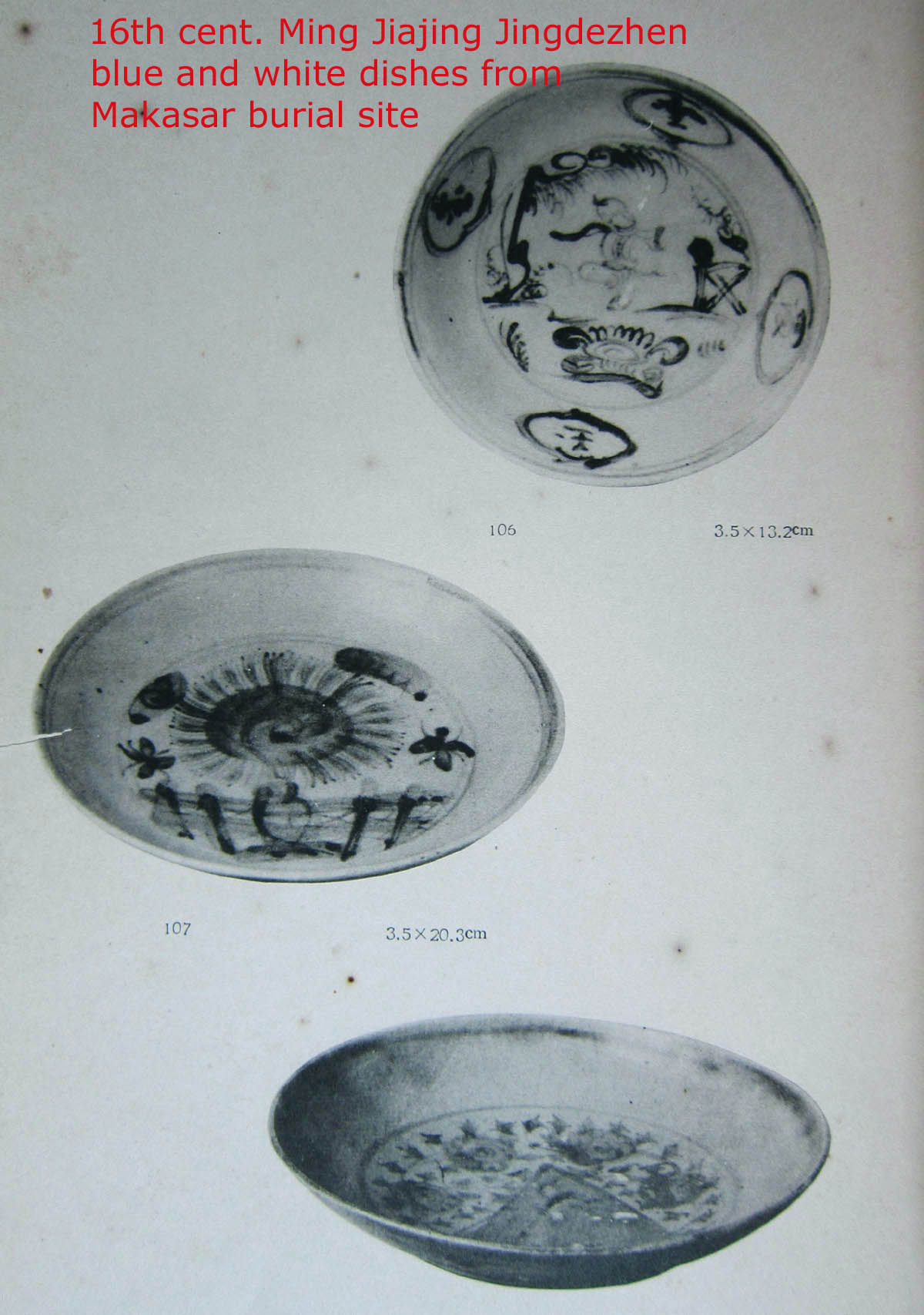

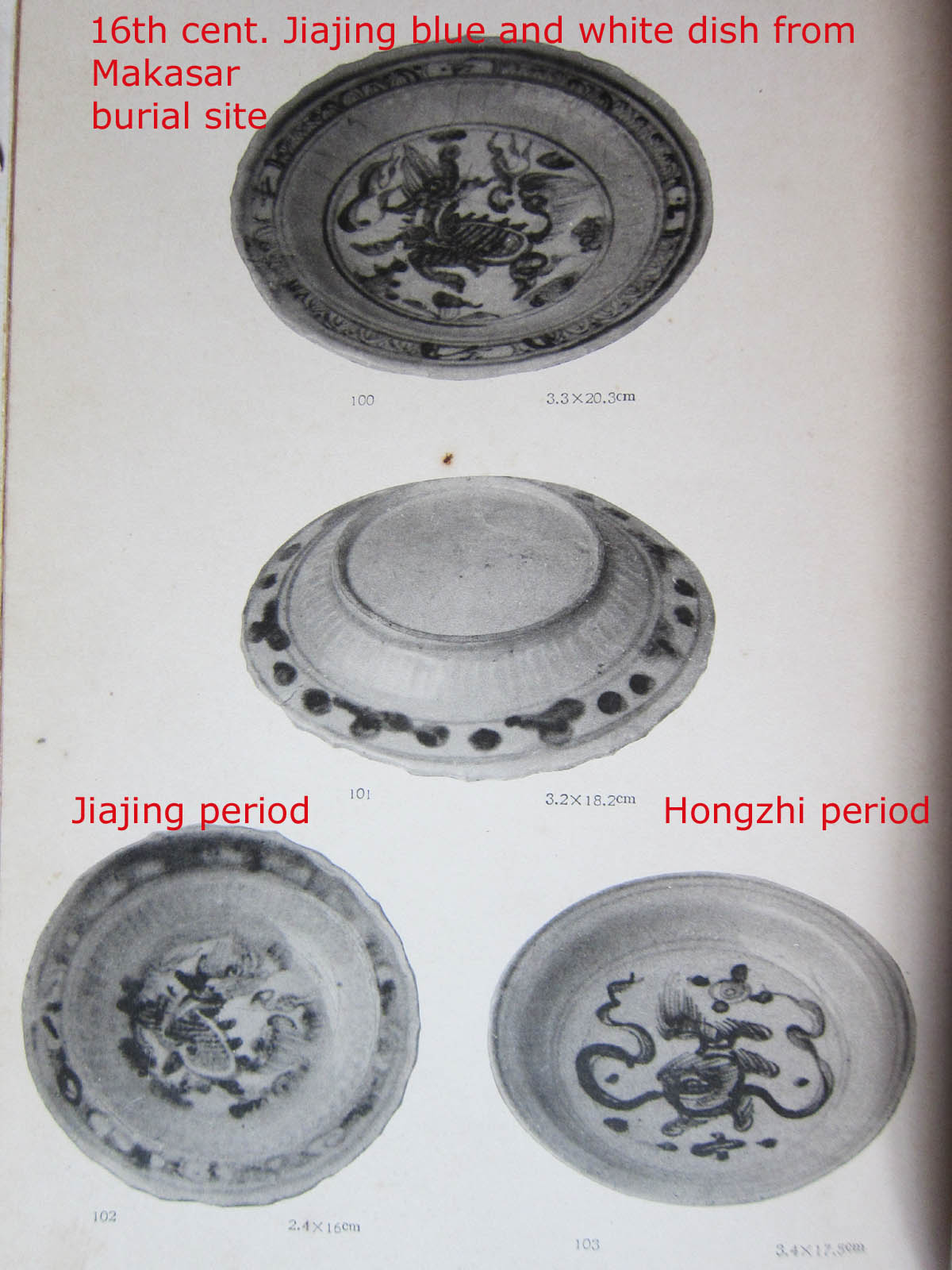

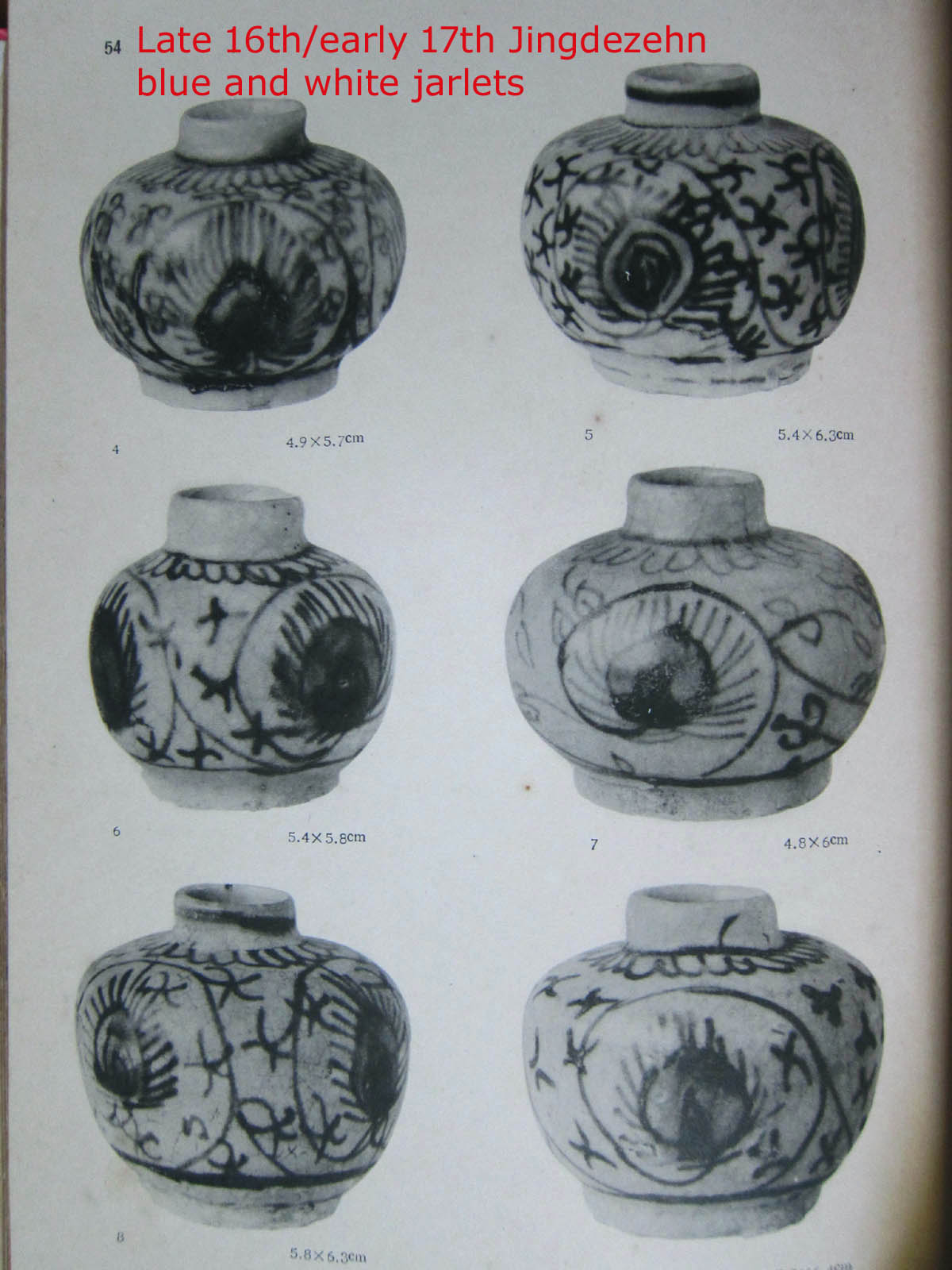

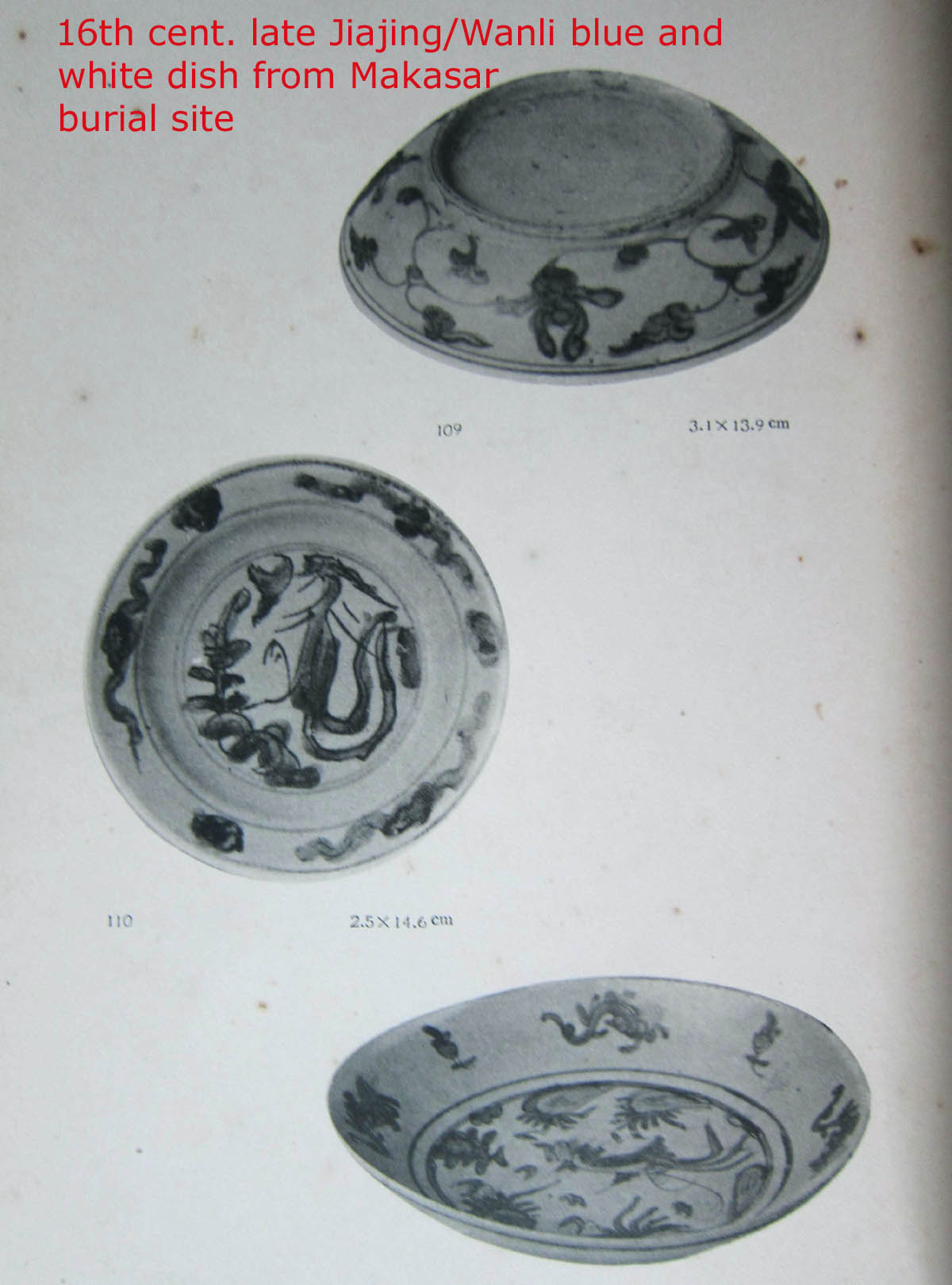

Excavated Ceramics from South Sulawesi

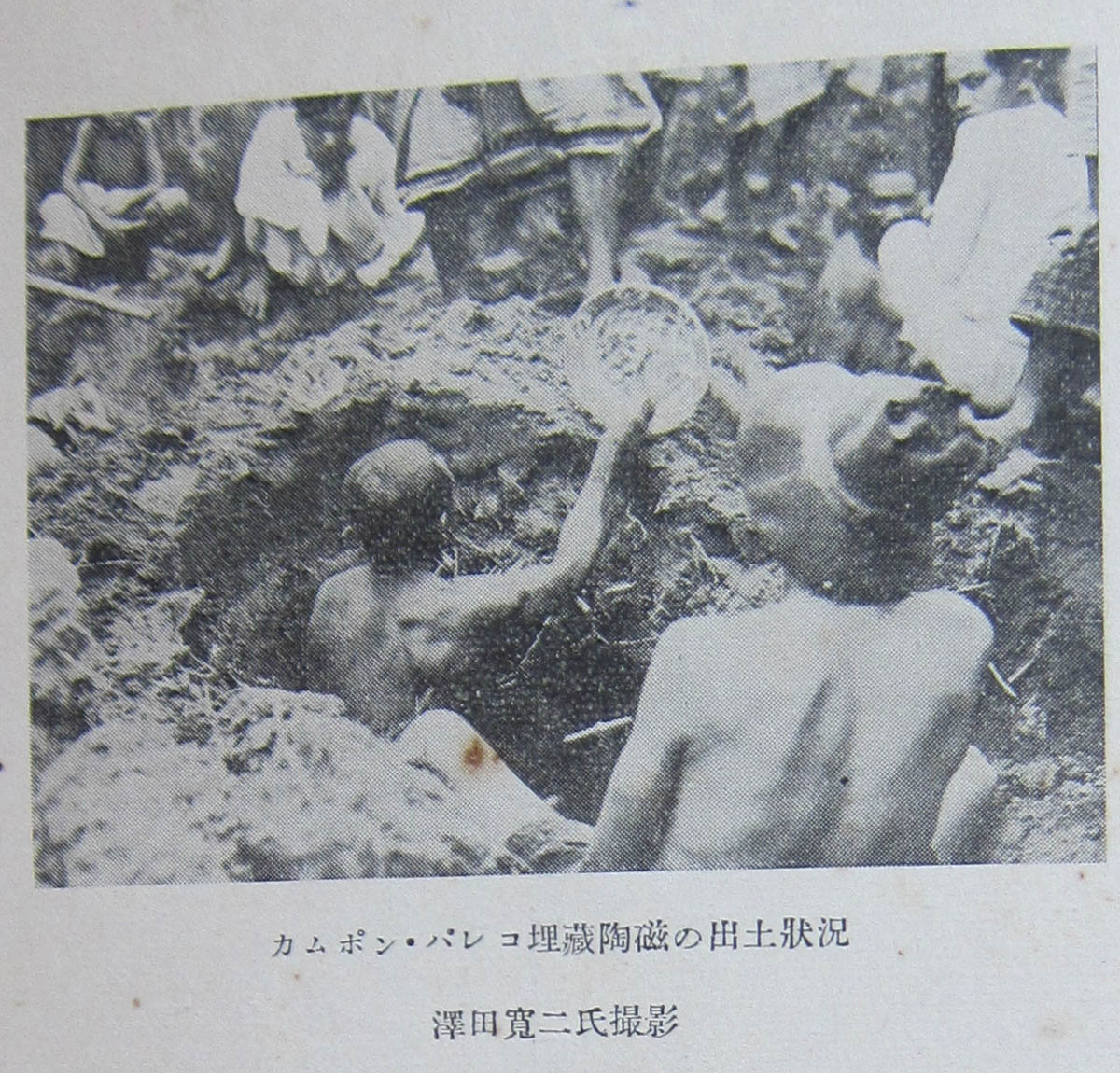

In 1930, excavations at Kampong Pareko, located between Takalar and Makassar, uncovered numerous ceramics dating from the 12th to 17th centuries. This site functioned both as an ancient settlement and burial ground. The ceramics found originated from China, Thailand, and Vietnam. Some Japanese collectors witnessed the excavations and acquired many of the pieces. Japanese ceramic scholars Ito and Kamakura later studied the collection and published their findings in Nanhai Gu Taoci (Ancient Ceramics of the South Seas), published in 1938.

The ceramics span from the Southern Song to the late Ming dynasty, with the majority dating to the 16th–17th century, corresponding with South Sulawesi’s peak as a center of regional and international trade. Many of the ceramic types are also found in burial and habitation sites across Indonesia and the Philippines.

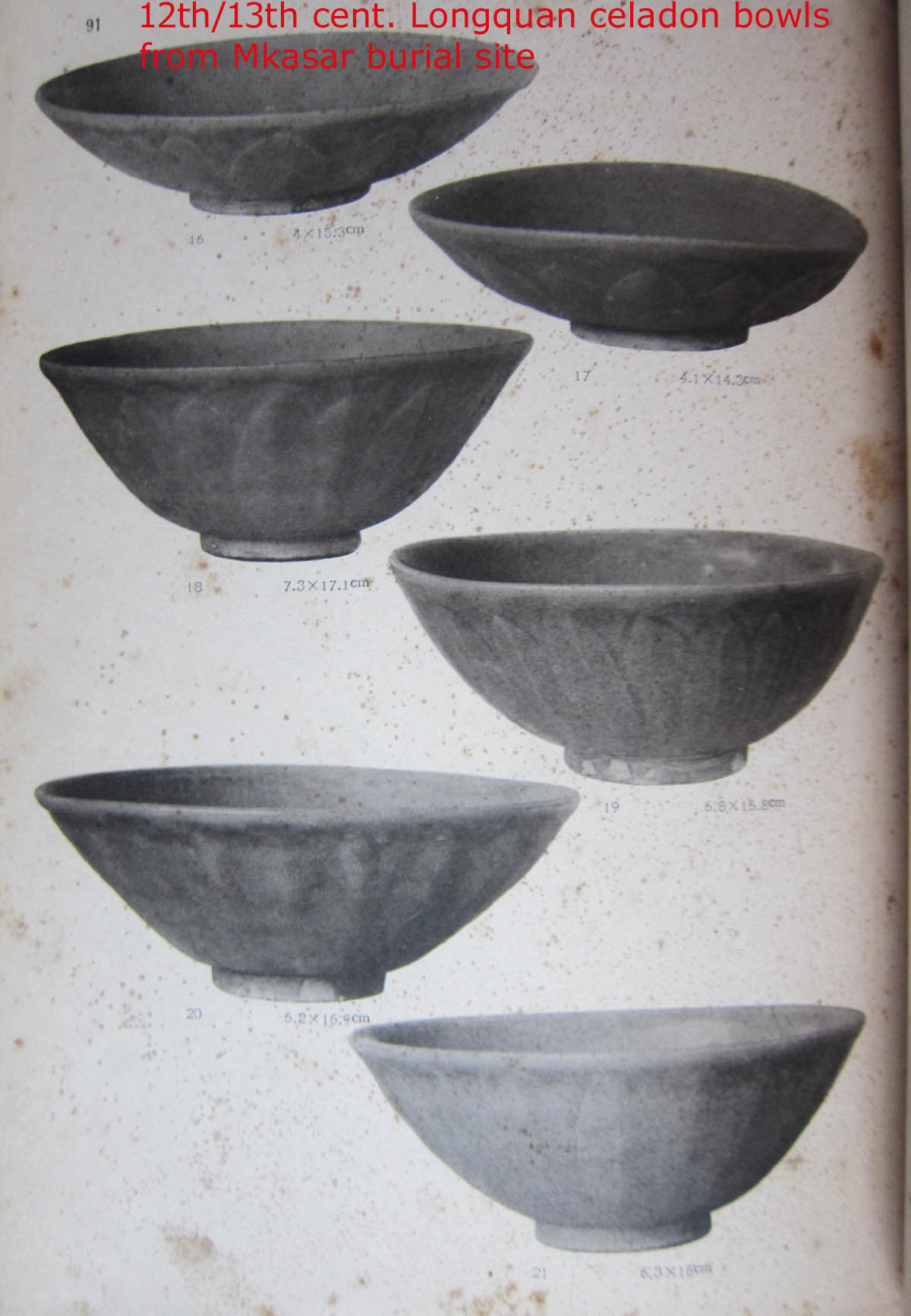

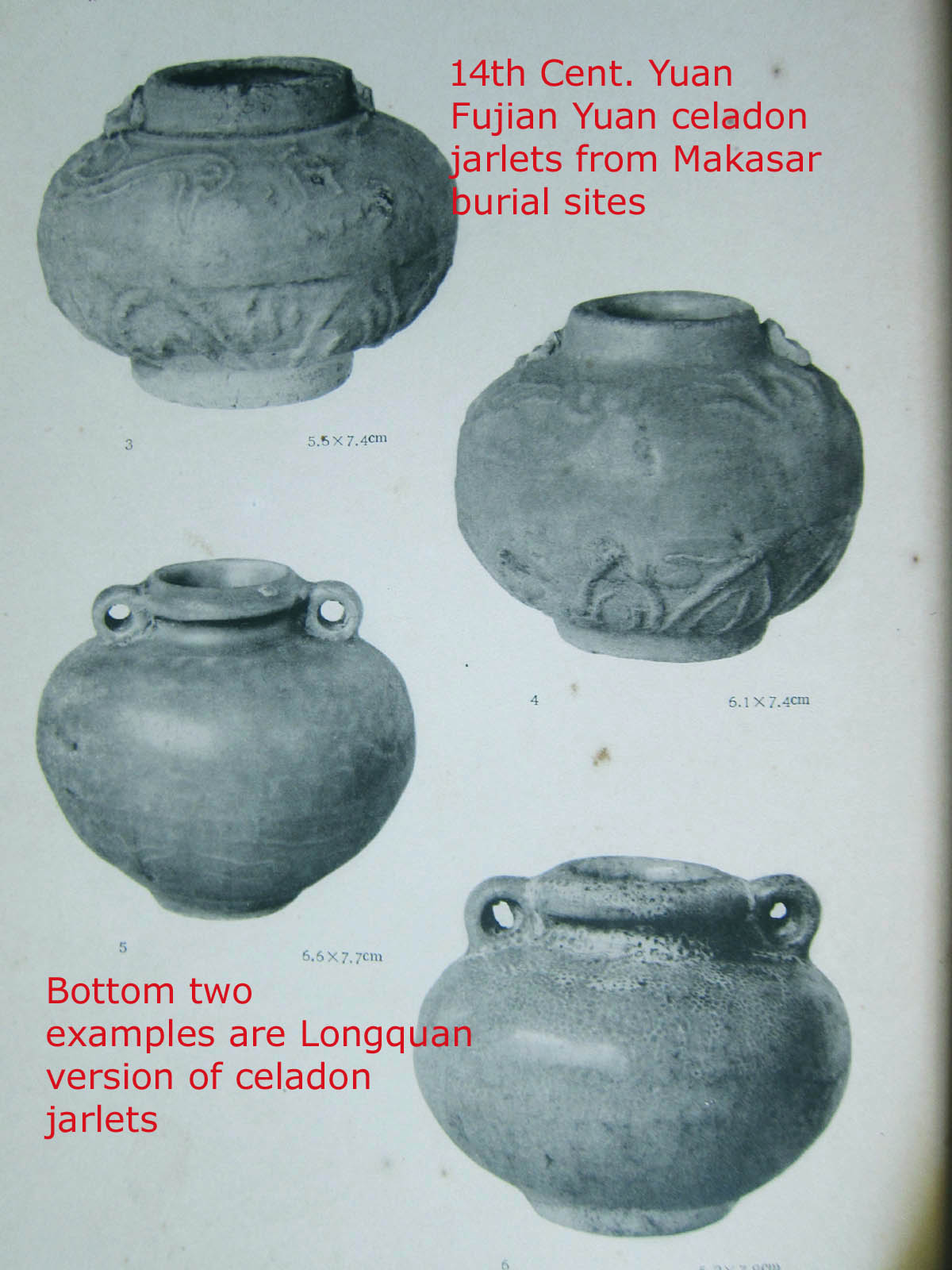

Southern Song/Yuan Period (12th to 14th Century)

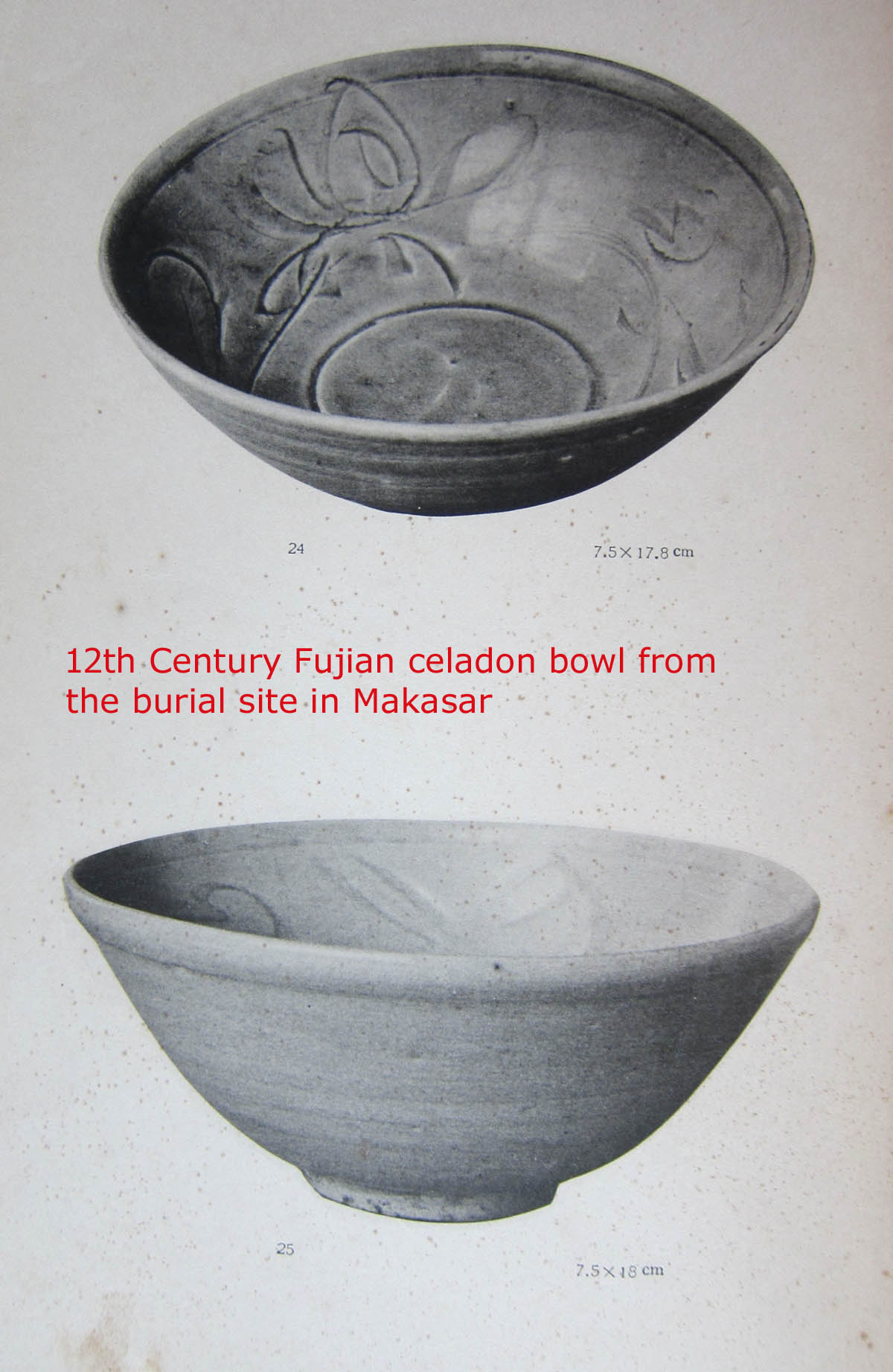

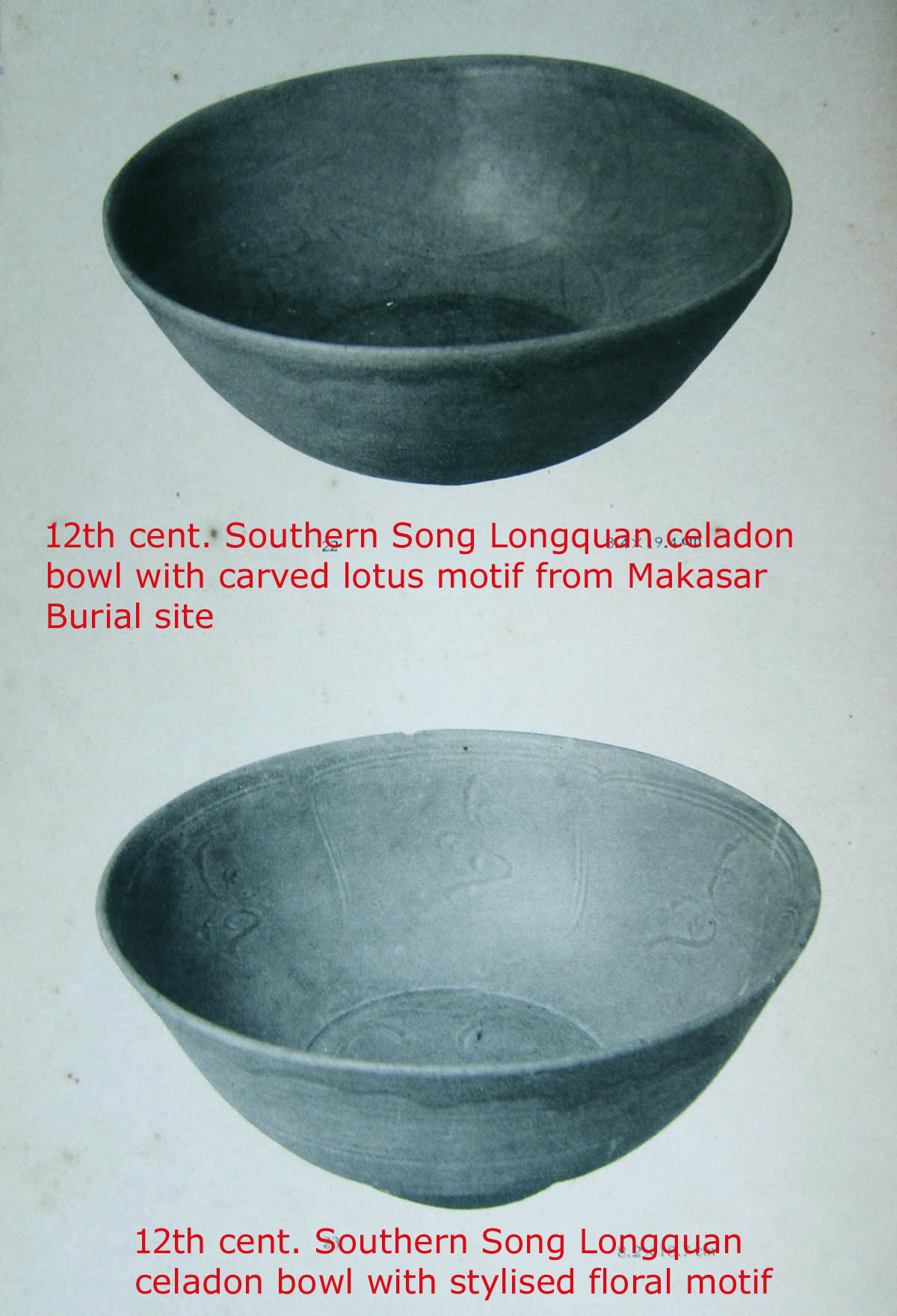

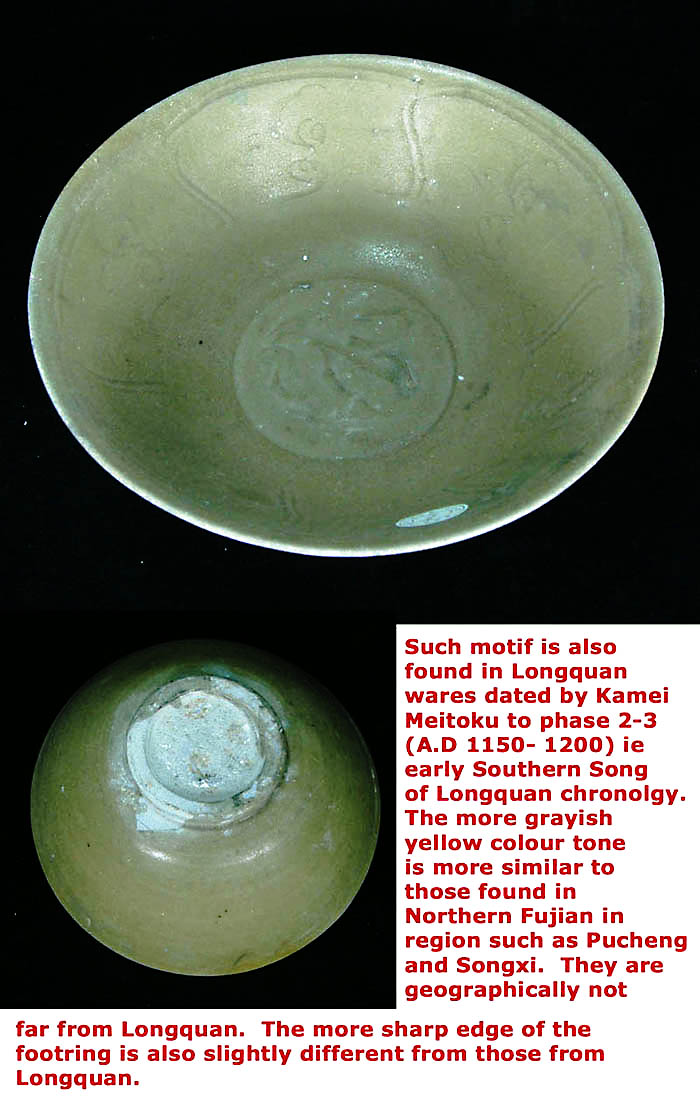

Some of the earliest finds are celadon wares dating to the 12th century, produced in Fujian and Longquan. Many are similar to those recovered from the Jepara shipwreck. A number of pieces with carved lotus motifs were identified, with the Longquan celadon examples being more finely potted and glazed.

Fujian celadon from the burial site

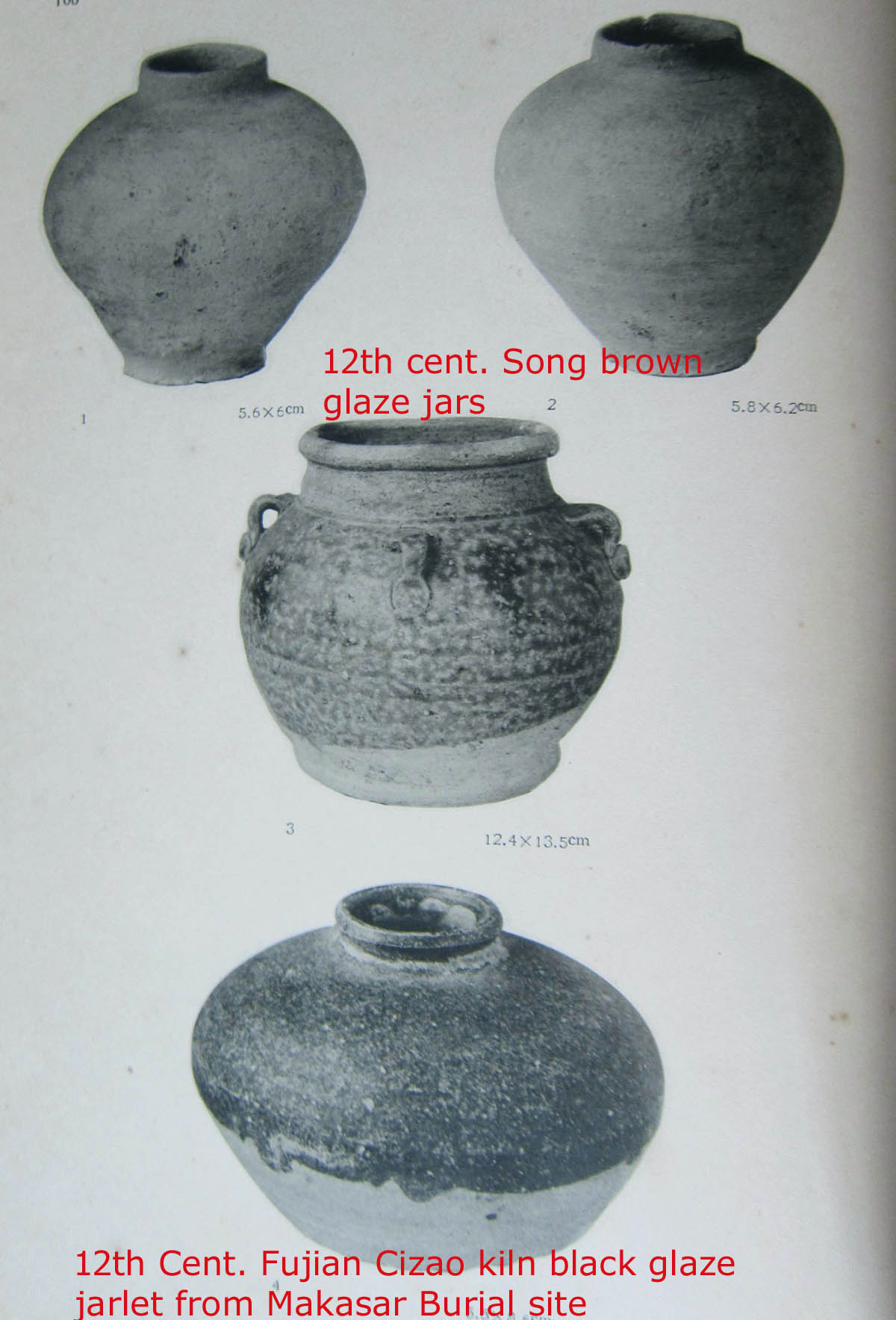

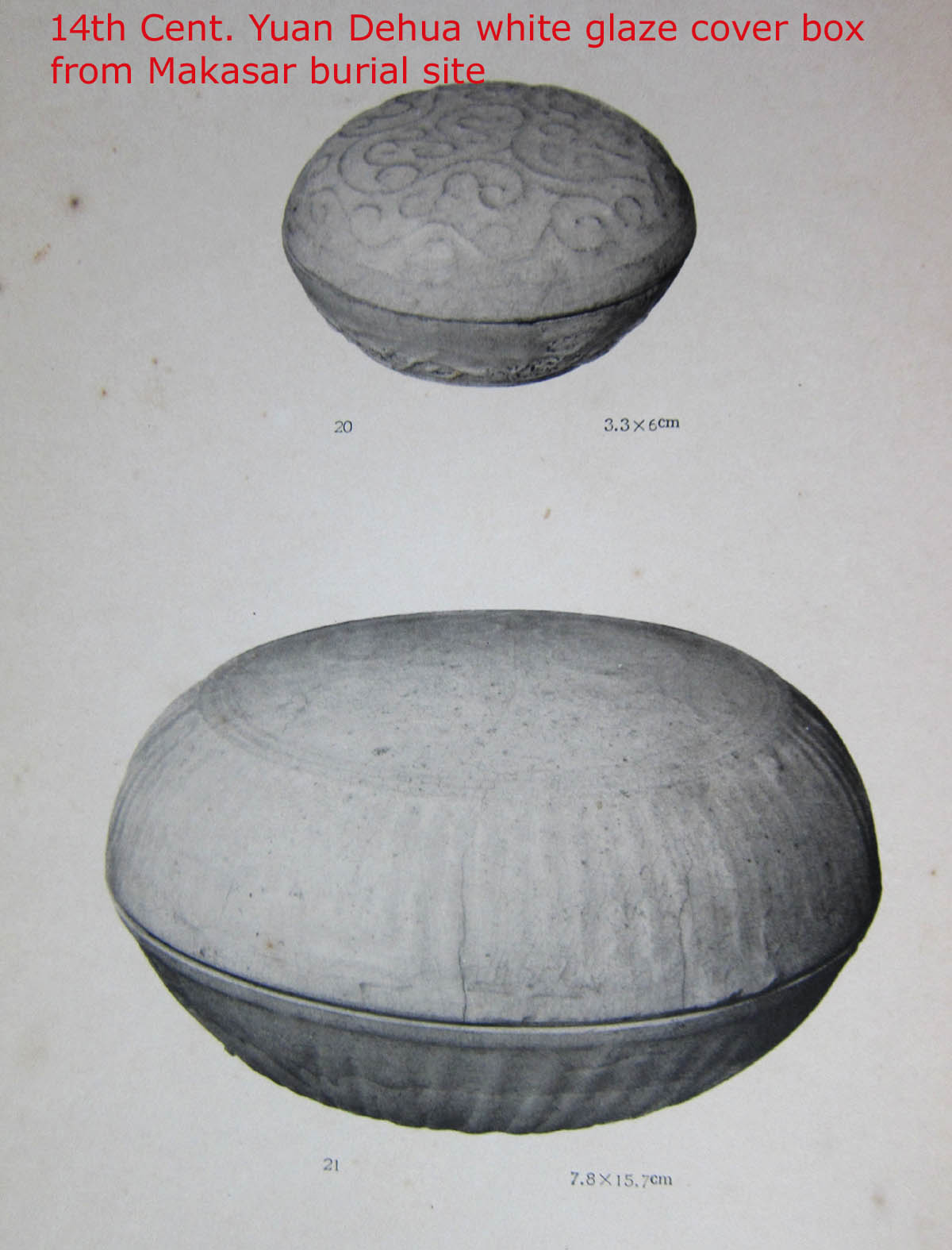

There were also many black and brown-glazed stoneware vessels from the Fujian Cizao kilns, as well as white-glazed vessels from the Dehua kilns, which remained popular into the Yuan period.

The bottom cover box is from the 12th century and also found in the Jepara wreck

Examples in the author's collection

The Jepara shipwreck provides a good survey of the types of export wares from the Southern Song period and quite a few types were found in the Makasar burial sites. For more on the cargo mix of the Jepara wreck, please read this article.

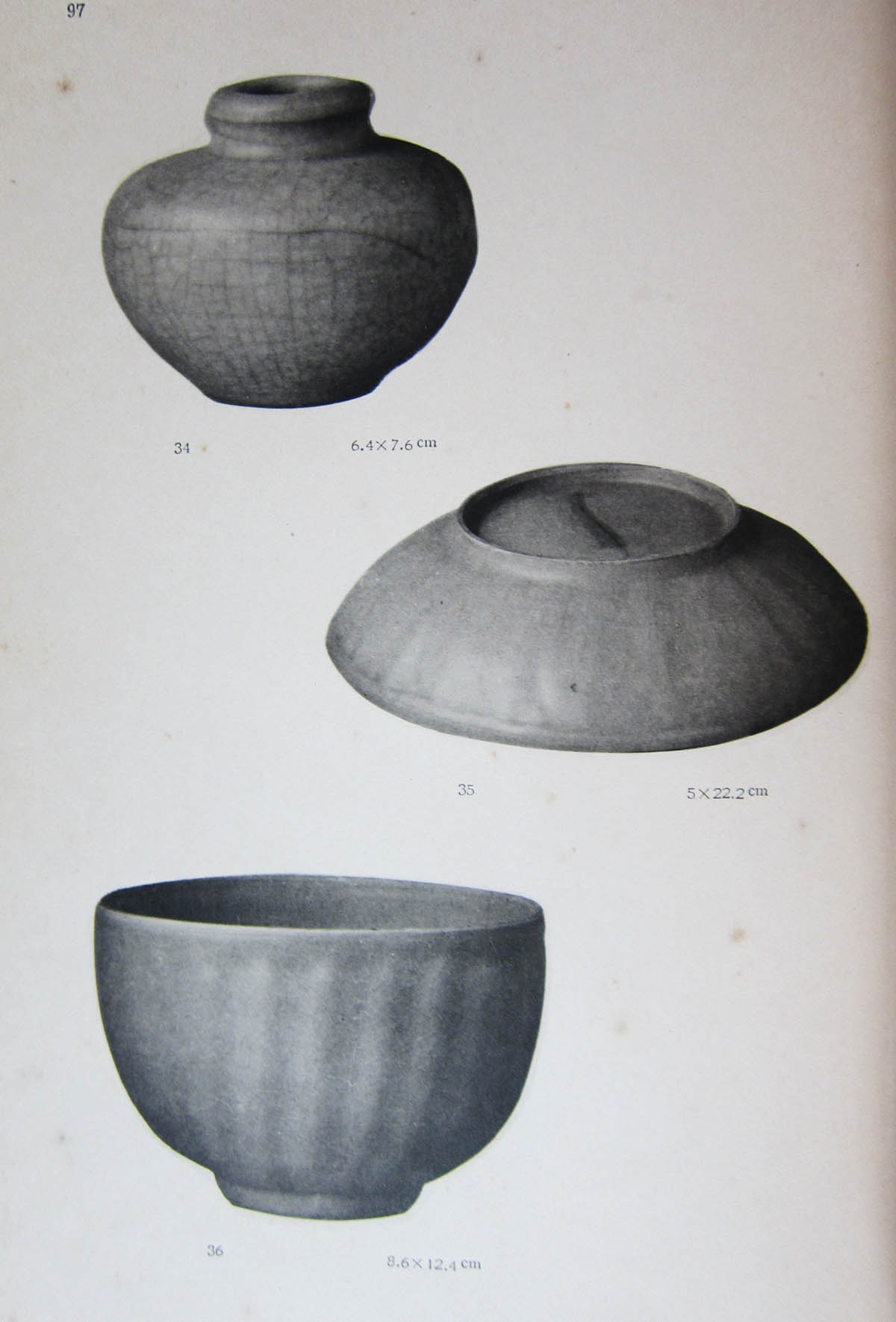

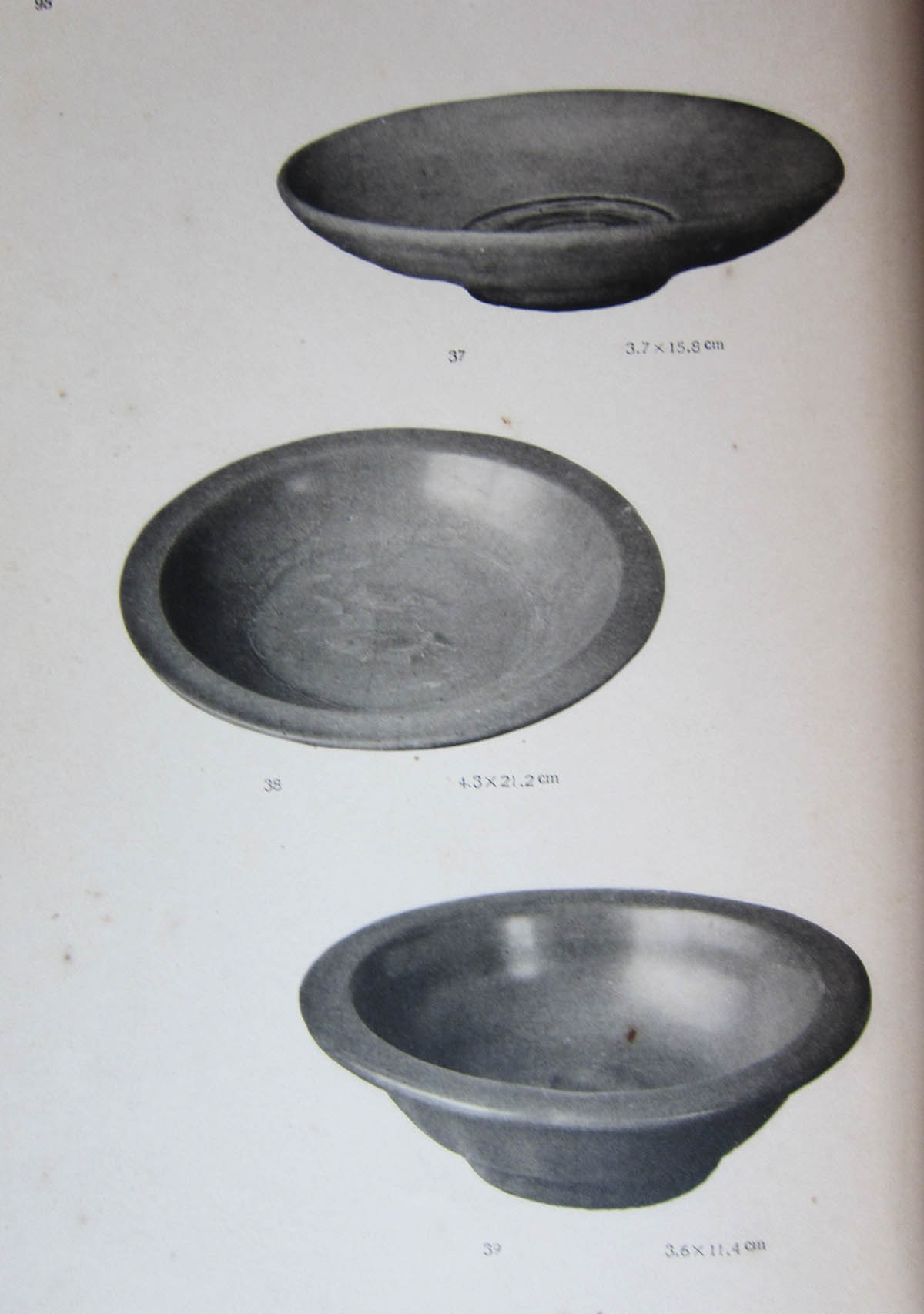

During the 13th/14th period, Longquan celadon wares became a major export item and also well represented in the Makasar burial sites. The vessels types found included jarlets, bowls and dishes. One of the most popular decorative motif is lotus petals on the external wall of bowls and dishes. Applique twin fishes on the interior of dishes is another popular motif.

Some similar examples from the author's collection

Besides Longquan, Fujian celadon and Dehua white glaze vessels with impressed motif were also found in some of the burial sites.

A similar Yuan Fujian celadon jarlet from the author's collection

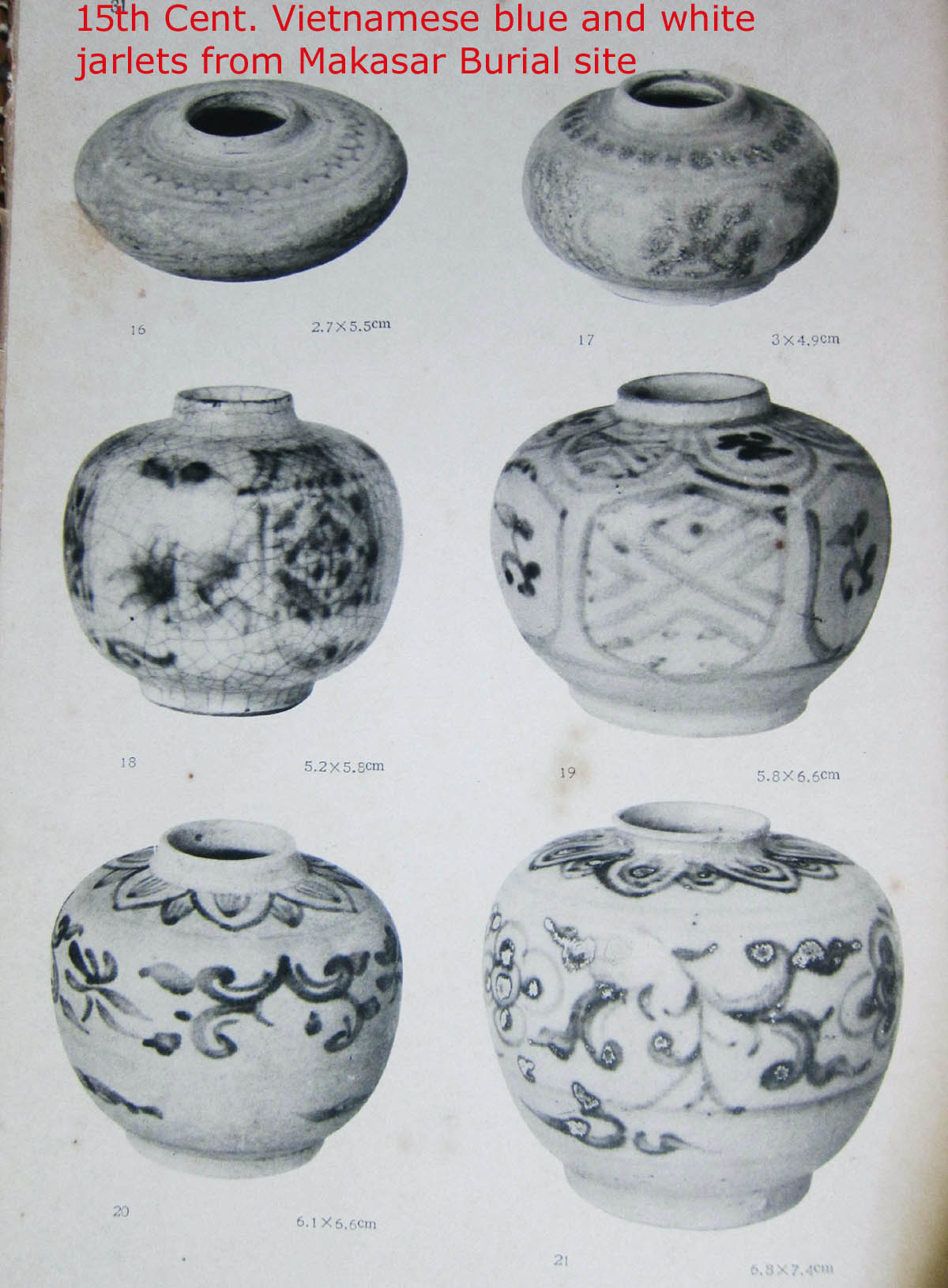

Ming Period (15th to 17th Century)

During the Hongwu reign (1368–1398) of the early Ming dynasty, the Chinese imperial court banned maritime trade, leading to a significant decline in the presence of Chinese ceramics in Southeast Asia. Consequently, few ceramic pieces from the early 15th century were found at the Makassar site.

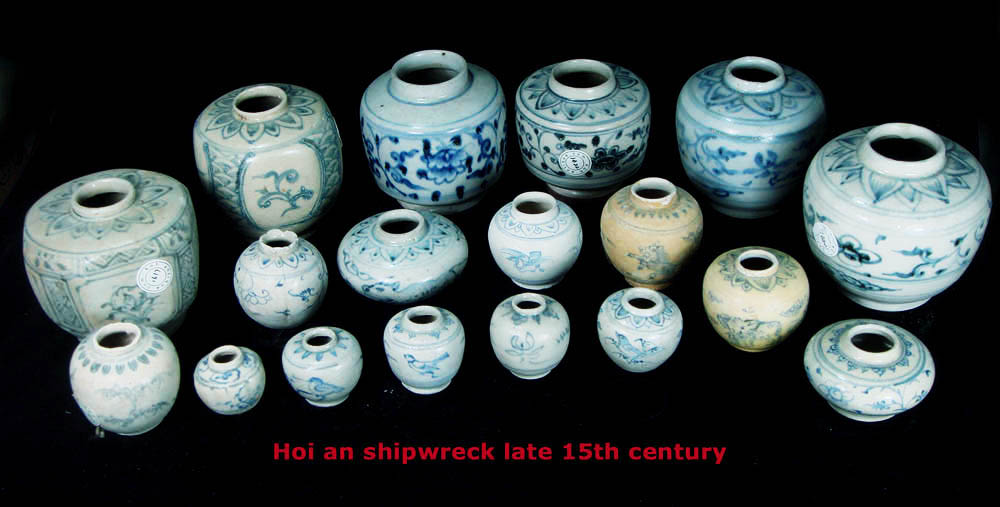

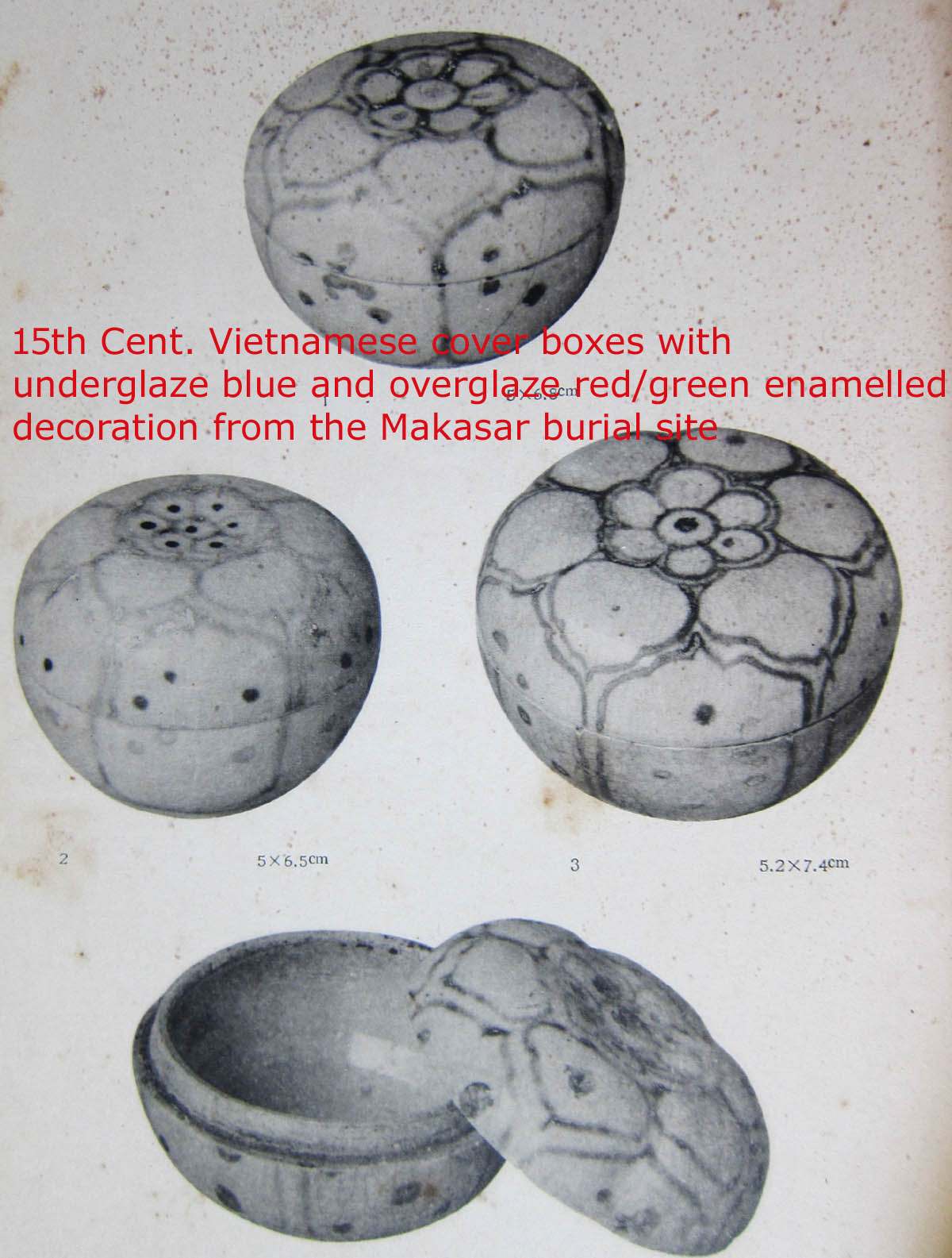

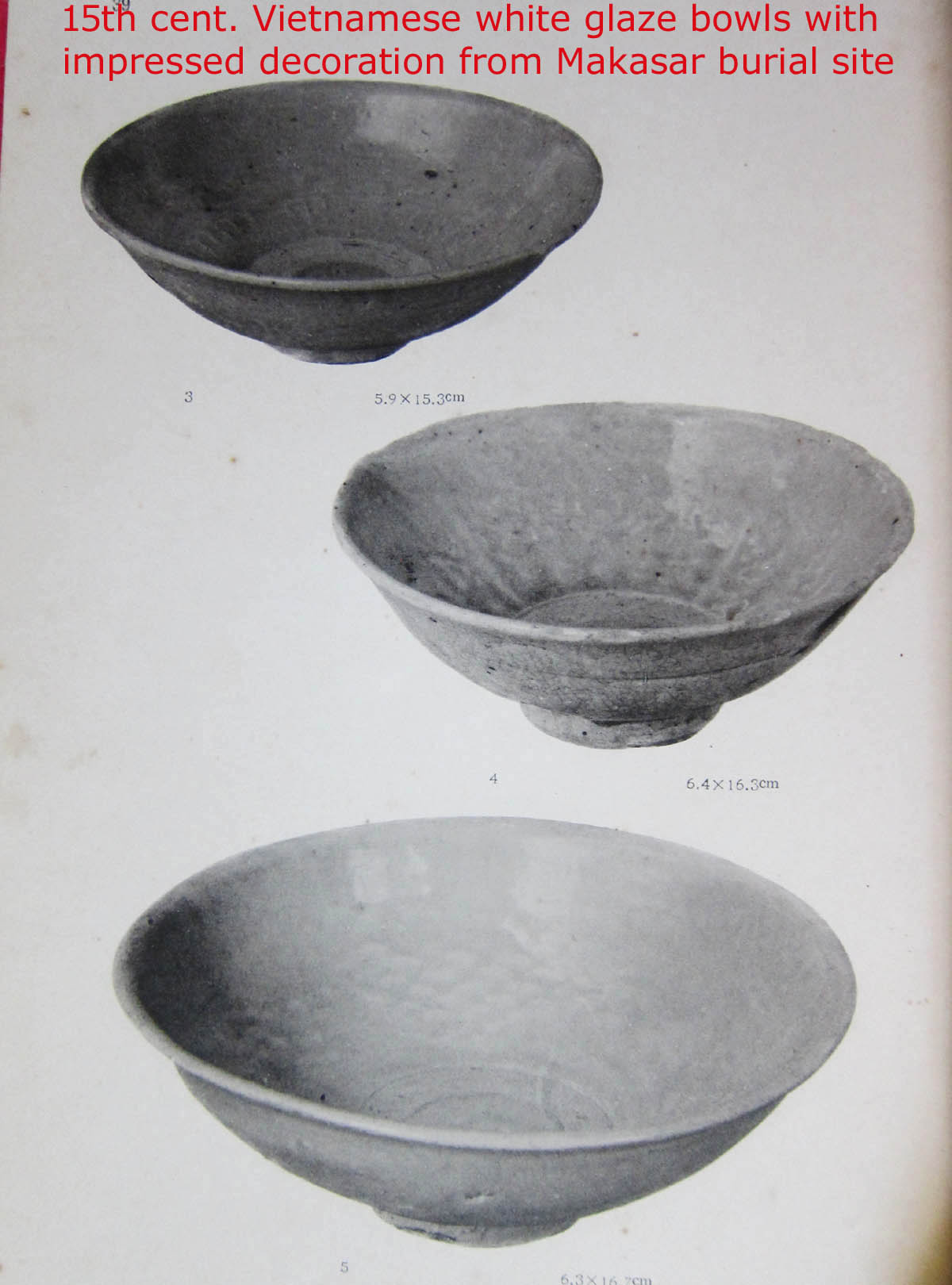

This created a window of opportunity for Vietnamese and Thai kilns to fill the void. Vietnam exported:

Similar white glaze bowls from the author's collection

While Vietnamese iron-brown wares were not documented in the Japanese publication, blue-and-white and overglaze decorated wares similar to those from the Hoi An shipwreck were found in Makassar.

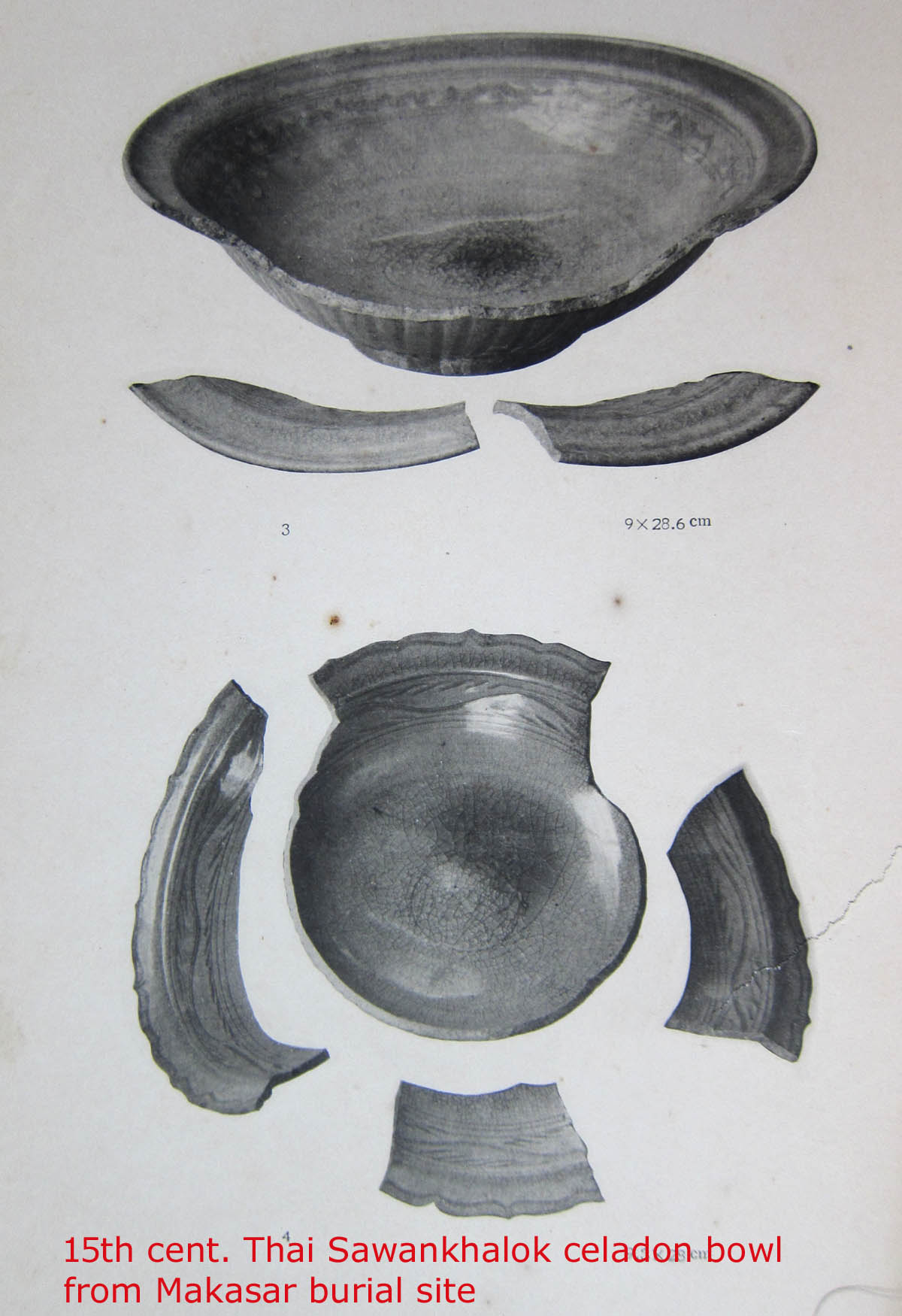

Similar Thai celadon big bowls from the author's collection

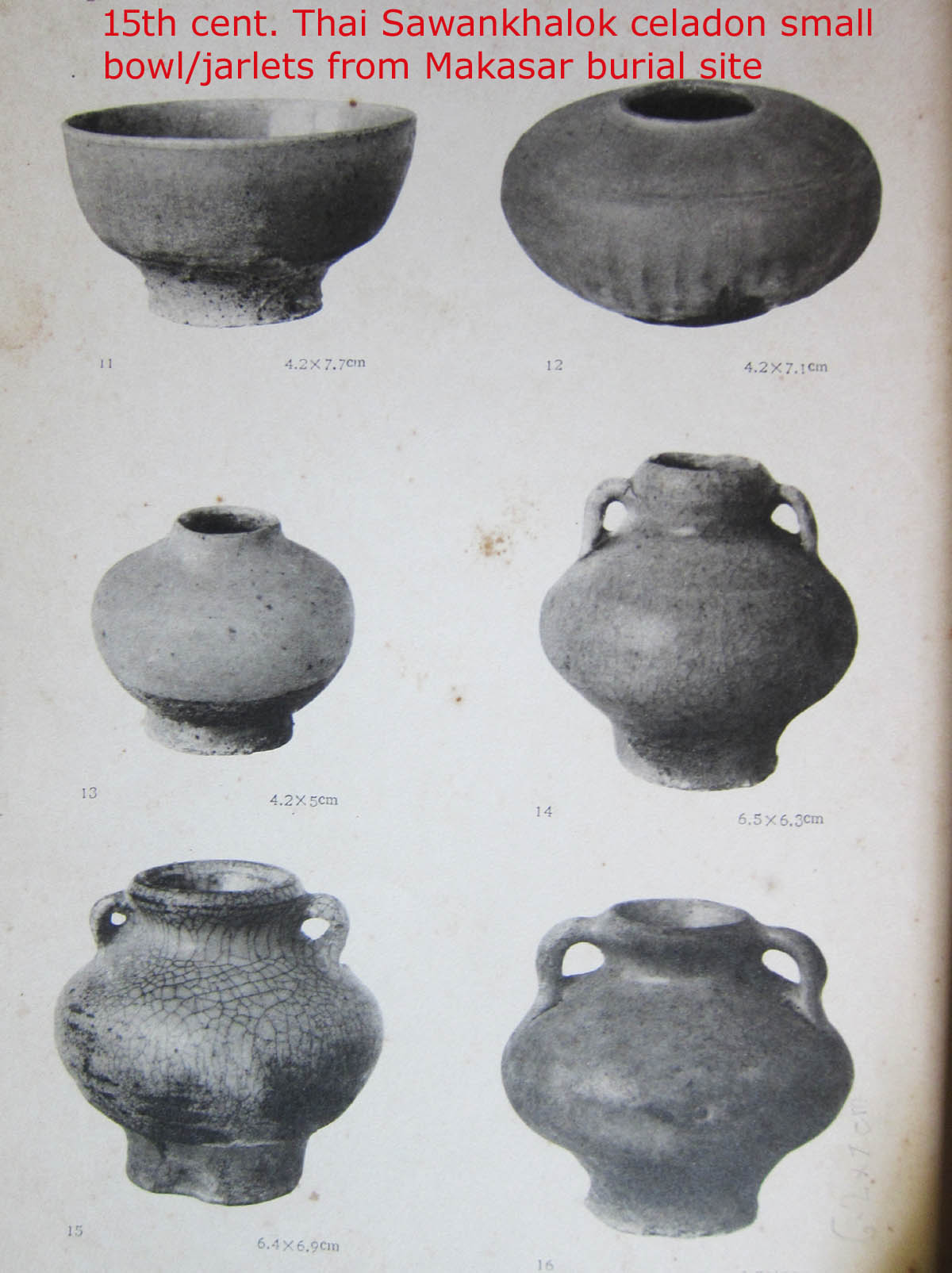

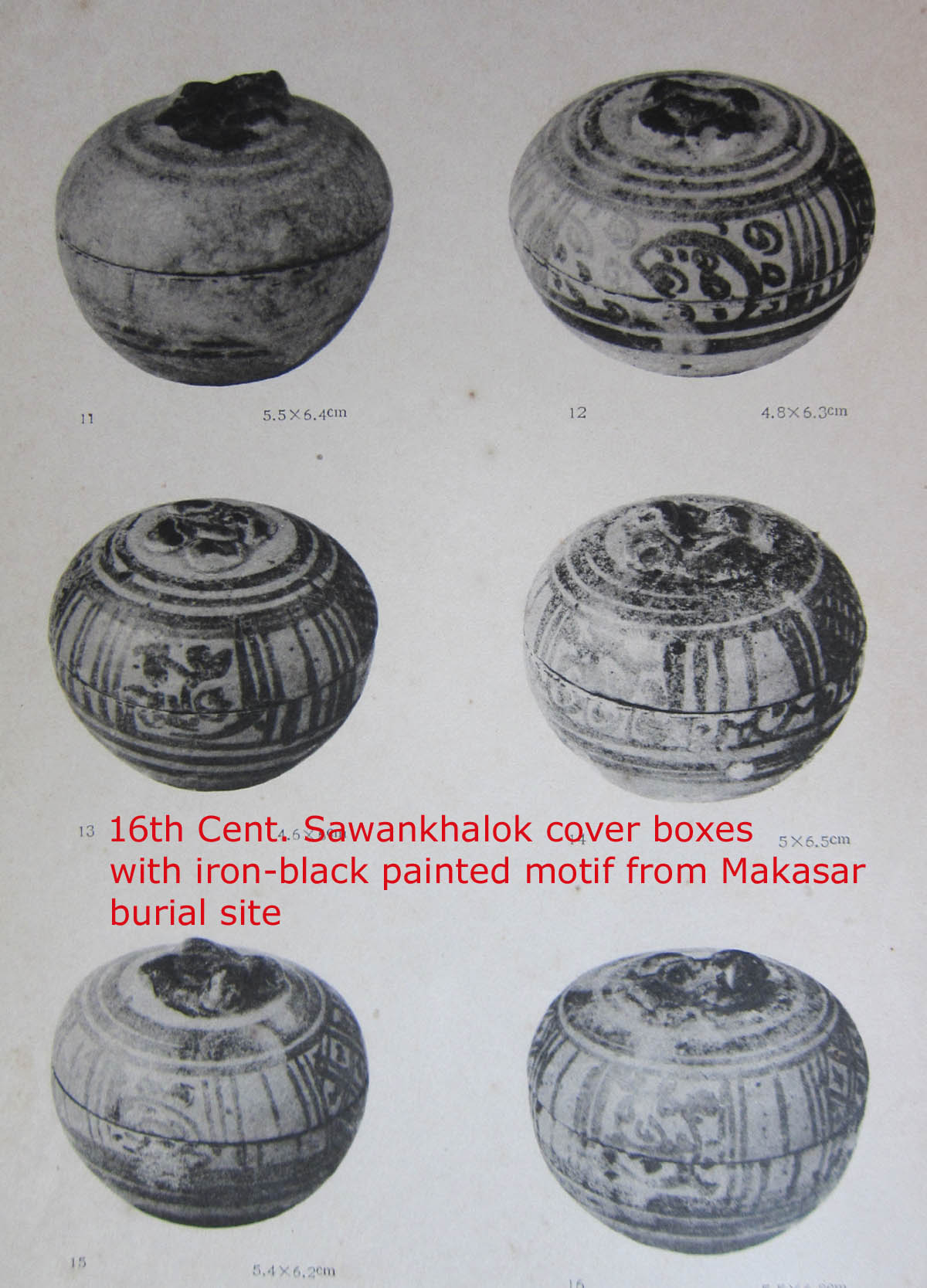

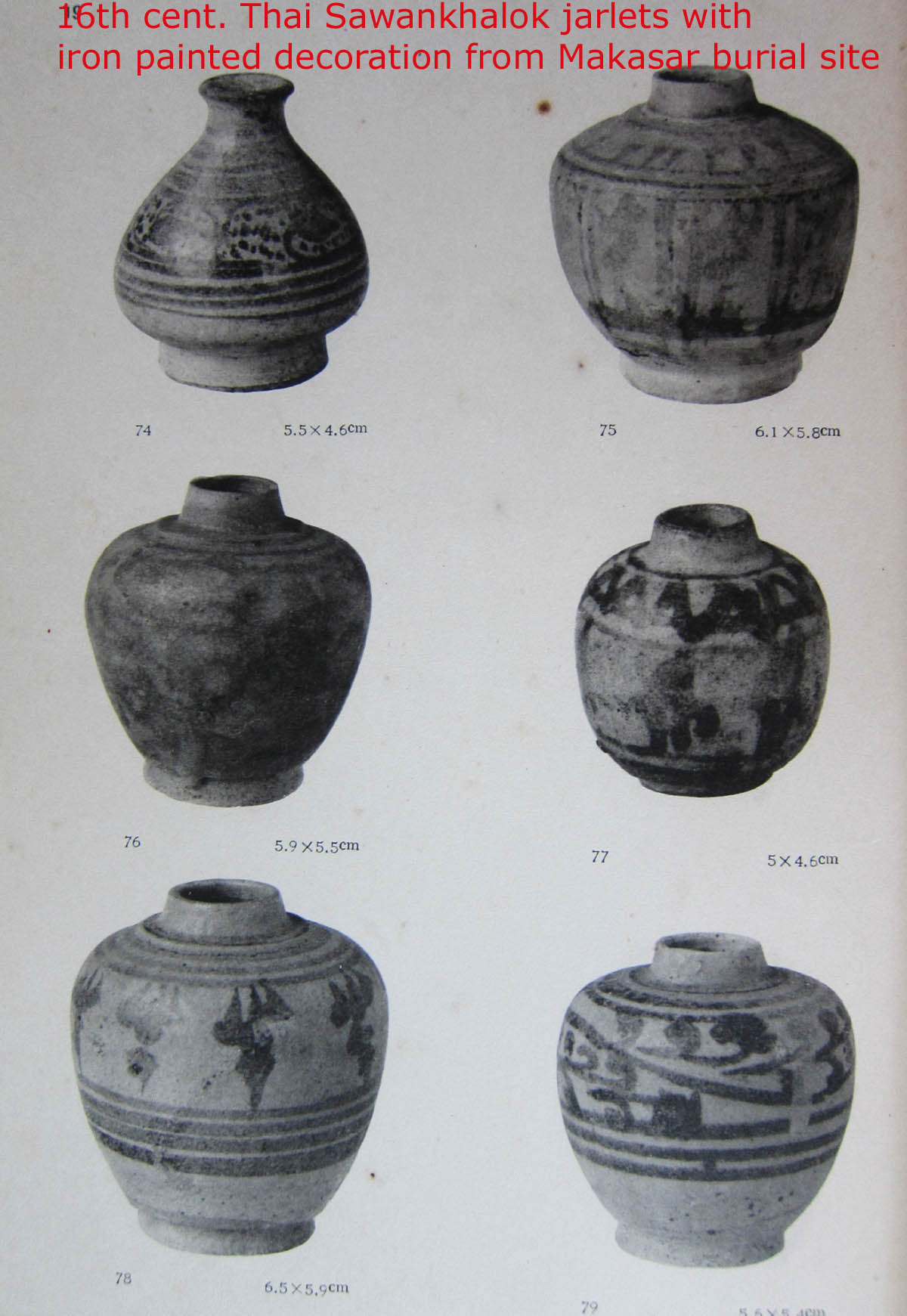

By the early 16th century, very few Thai celadon were produced. Many Chinese ceramics especially blue and white wares again found their way to Southeast Asia despite the Chinese Imperial Court's continued ban on maritime trade. During the first half of 16th century, the demand for Vietnam and Thailand ceramics dwindled. The only type that was in demand was a newly introduced Sawankhalok iron-black painted decorated wares, especially cover boxes and jarlets. The Singtai and Xuande wreck dated to 1st half of 16th century carried some quantities of such wares. Another new type is ware with brown glaze decoration on white ground. For more on Thai trade ceramics, please read this article.

Similar examples from the author's collection

Example with decoration in brown on white ground in author's collection

Similar jarlets also found in Makasar burial sites

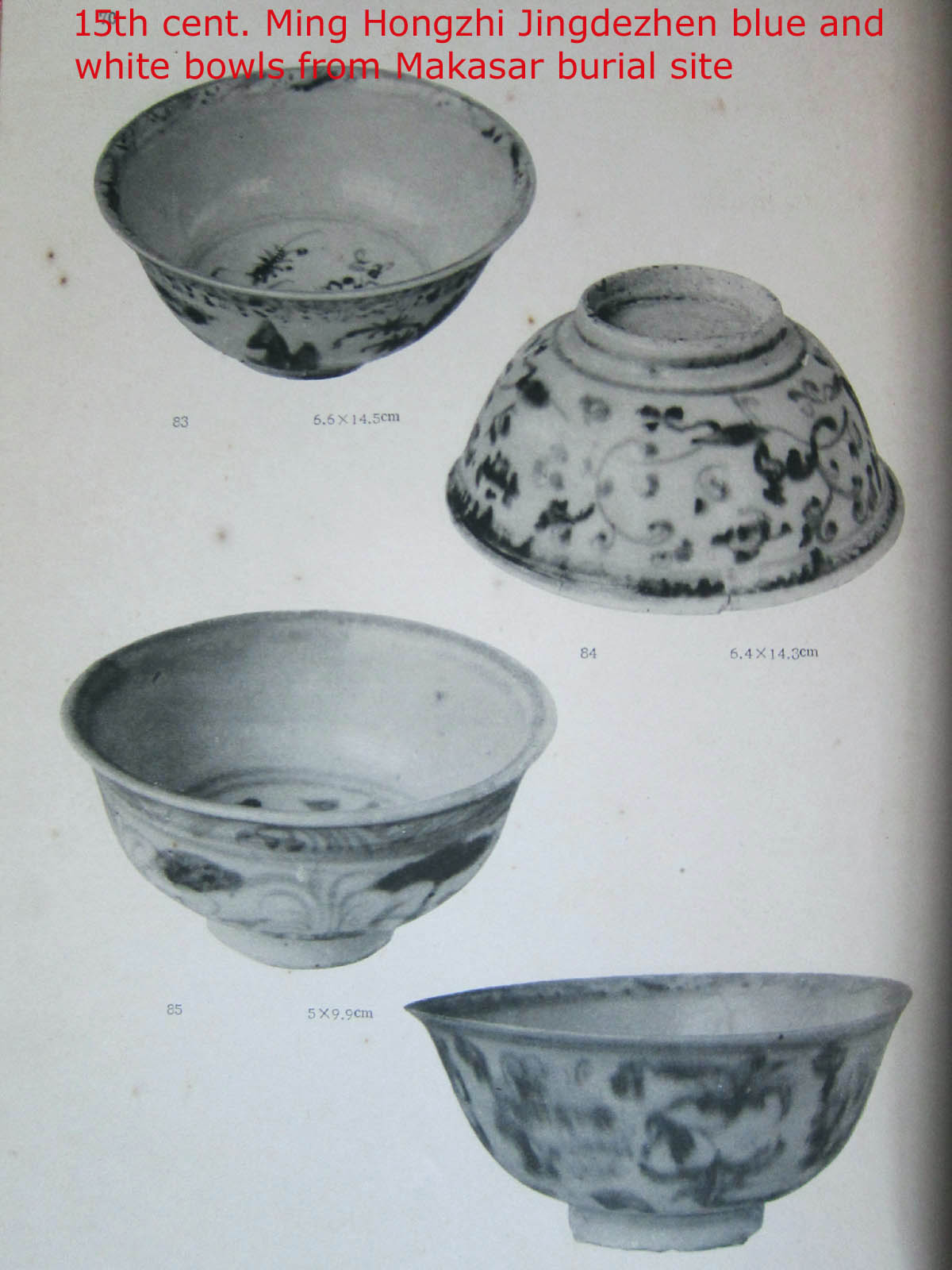

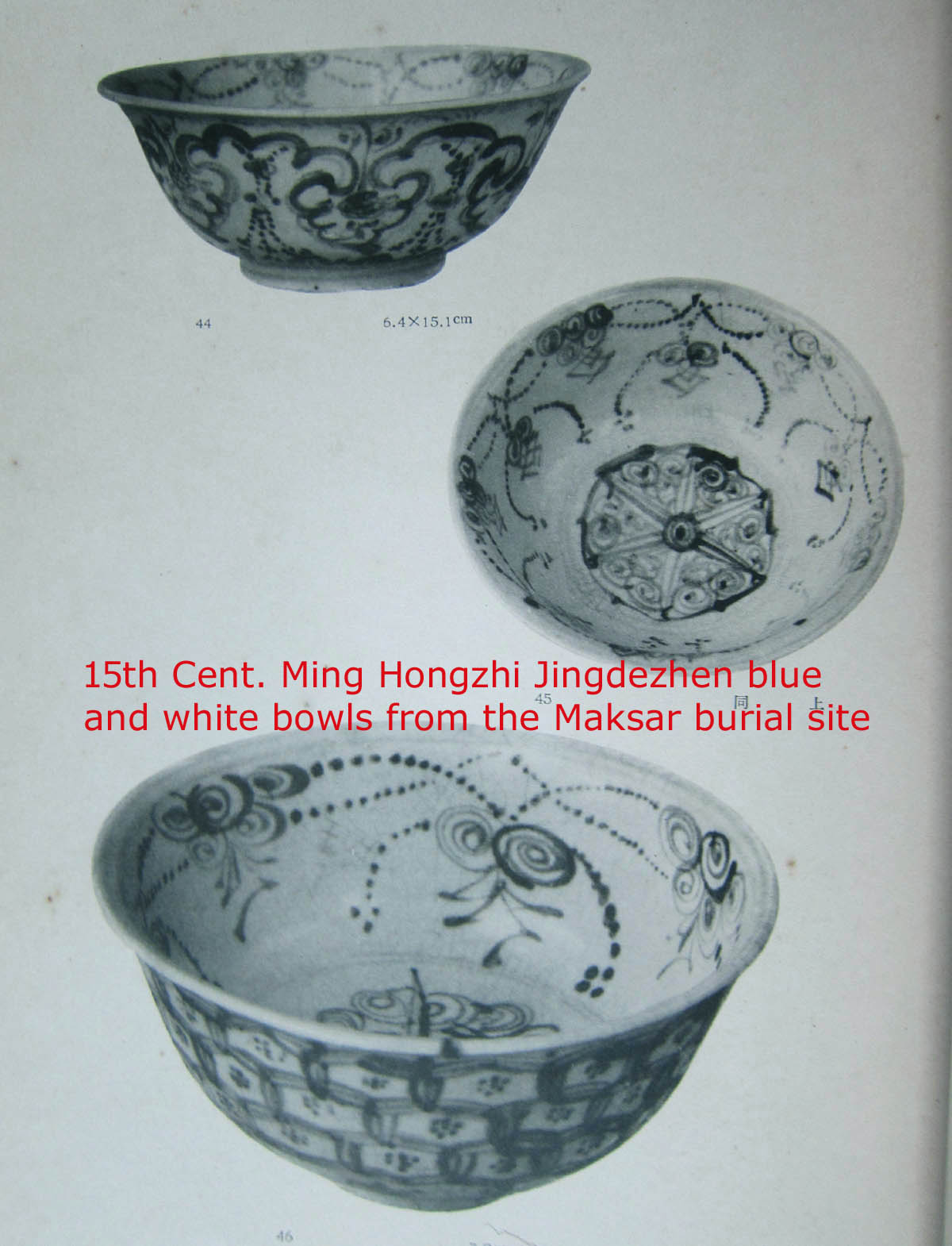

By the Hongzhi reign (1488–1505), Jingdezhen blue-and-white porcelain once again dominated Southeast Asian trade. Numerous Ming blue-and-white examples were found at Makassar, including dishes with phoenix motifs.

A similar Ming Hongzhi blue and white from the author's collection

Similar Ming Blue and white examples from the author's collection

Example with pheonix motif from the author's collection

During the Jiajing period (1522–1566), the Zhangzhou kilns in Fujian began producing blue-and-white export ware. These are:

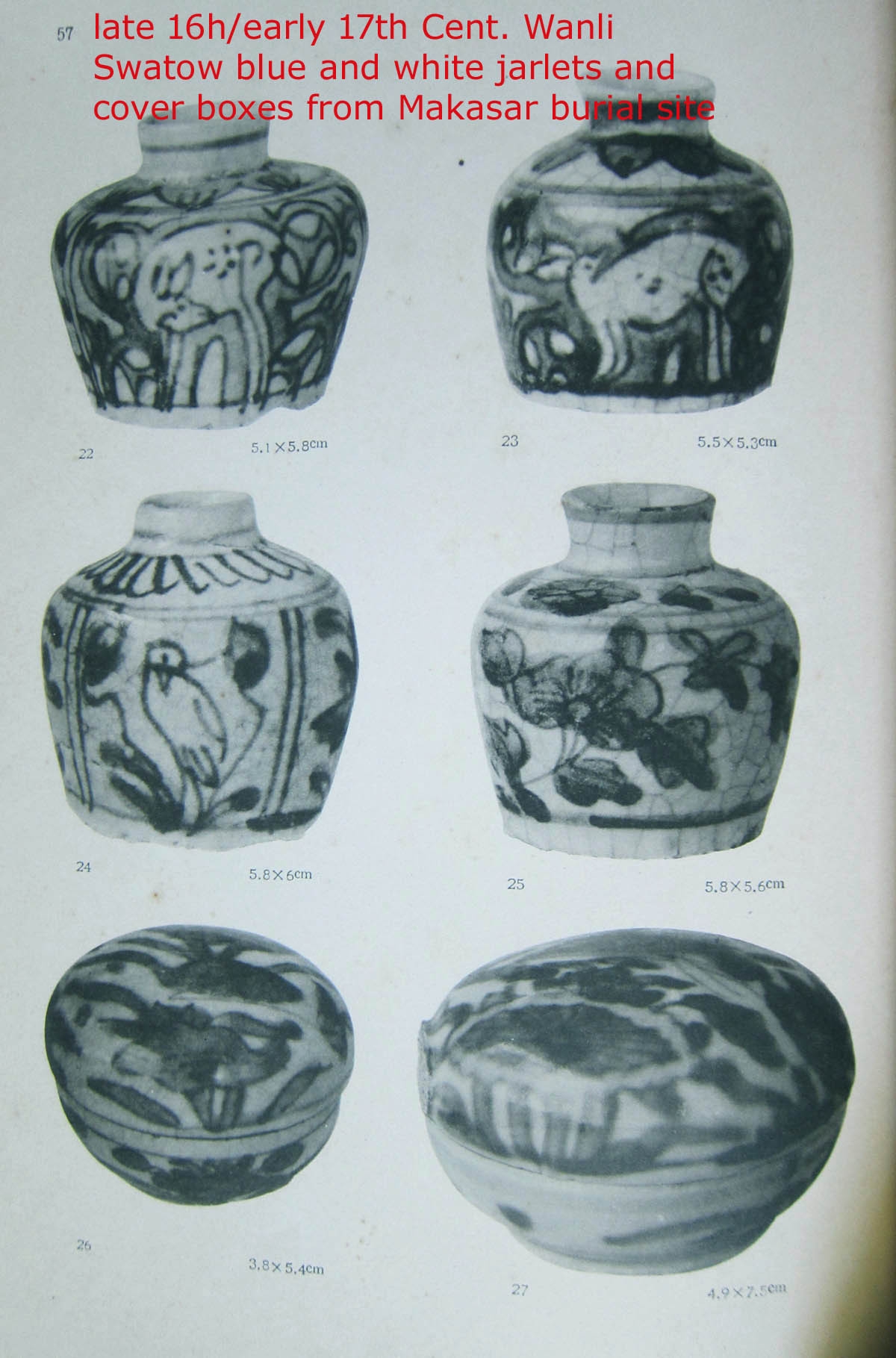

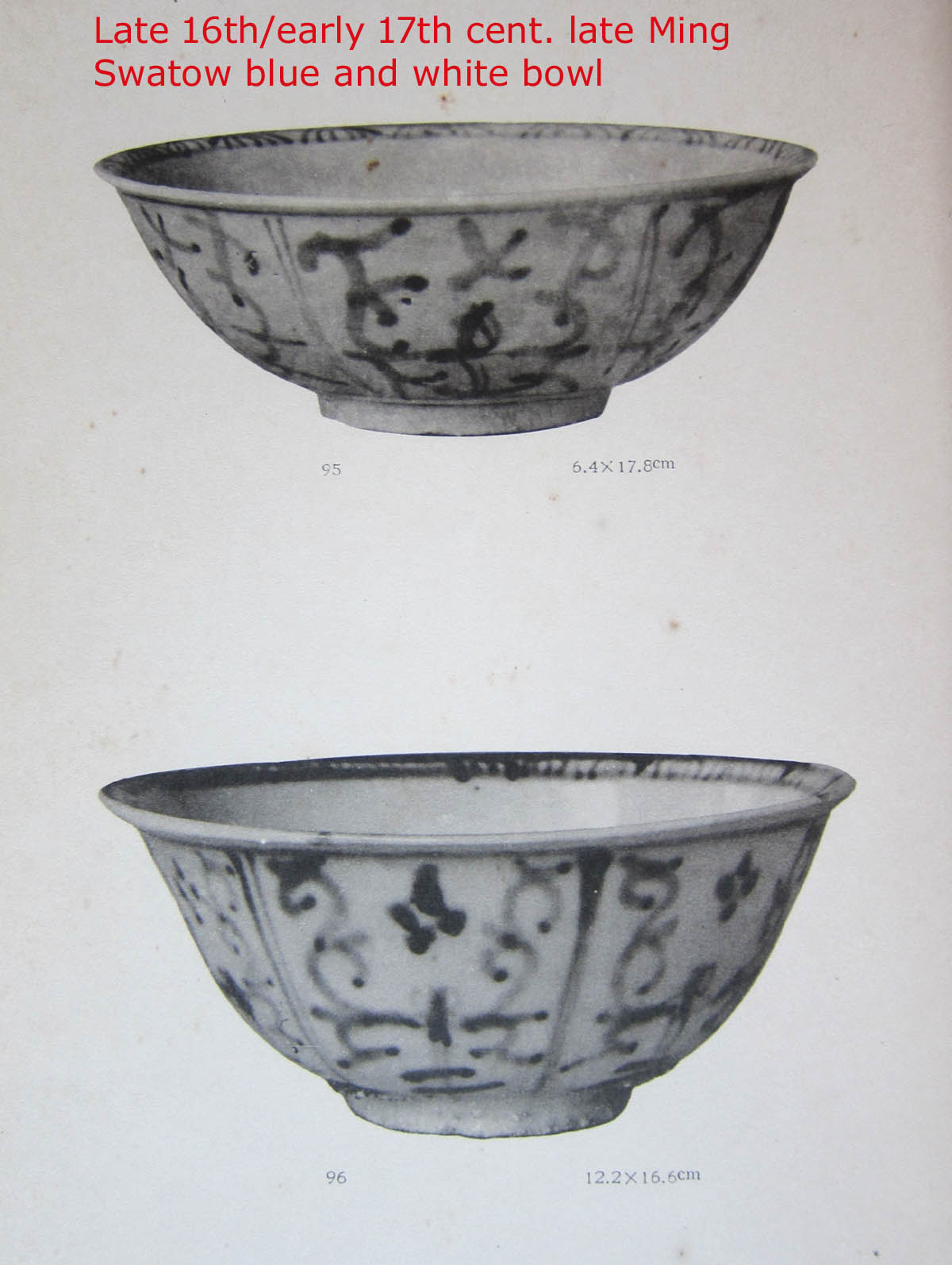

By the Wanli reign (1573–1620), Zhangzhou wares became dominant in the region, offering affordable alternatives that gained widespread popularity.

.

Example with deer motif from the author's collection

The ceramics excavated from Kampong Pareko reflect South Sulawesi’s vibrant participation in international maritime trade from the Southern Song through the late Ming period. The diversity of ceramic types — from Chinese celadon to Vietnamese enamelled wares and Thai iron-painted vessels — attests to Makassar’s strategic role as a crossroads of Asian commerce during its golden age.

Written by: NK Koh (13 Sep 2014)