Relationship Between Falangcai, Yangcai, Fencai, and Famille Rose

The terms Falangcai (珐琅彩), Yangcai (洋彩), Fencai (粉彩), and Famille rose often cause confusion due to their overlapping references to overglaze enamelled wares. These wares are characterized by opaque, powdery enamels. Understanding the distinctions between Falangcai, Yangcai, and Fencai requires a historical and technical perspective.

The term Fencai emerged during the late Qing period. It was first documented in the 32nd year of the Guangxu reign by Ji Yuansuo Chenliu (寂园叟陈浏) in Tao Ya (陶雅), where it was described as a "powdery color" enamel due to its opaque and soft appearance. Fencai is also referred to as Ruancai (软彩), meaning "soft color," in contrast to the transparent, hard-textured enamels used in Wucai wares.

In 1935-1936, imperial porcelains from the Beijing Palace collection were exhibited in London. Some previously catalogued as Yangcai were relabeled as Fencai during the exhibition, highlighting the evolving terminology. Over time, Yangcai became less commonly used and was often categorized under Fencai.

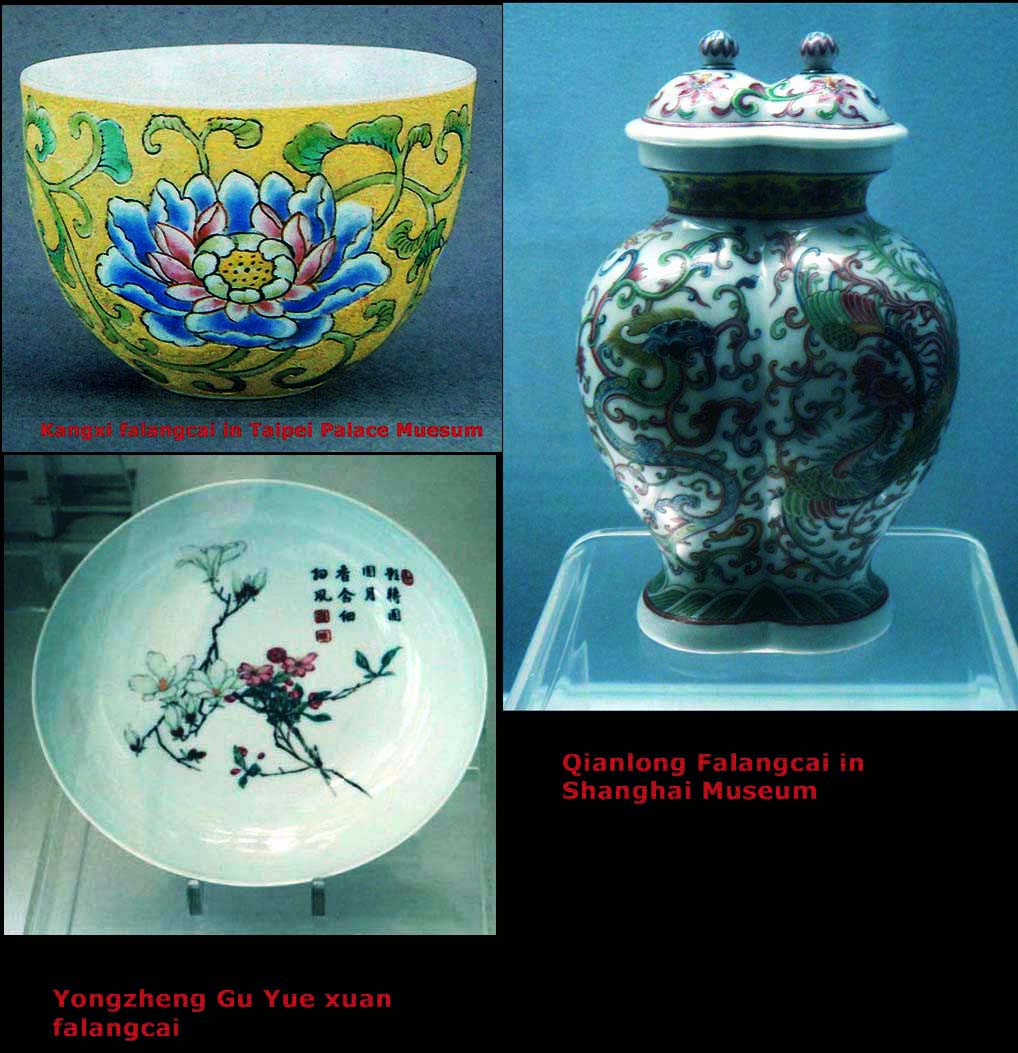

The term Falangcai originated during the Kangxi period and referred to enamels derived from European techniques, first seen on cloisonné wares presented to Emperor Kangxi.

Yangcai was first mentioned in the 13th year of Yongzheng's reign (1735) by Tang Ying (唐英) in A Brief Account of Ceramics (陶务叙略碑记). He described Yangcai as an imitation of the Falang style. The term implies foreign influence, either in the enamel composition or artistic style. According to traditional Chinese accounts, Fencai developed by combining techniques from Wucai and Falangcai, making Yangcai a hybrid form.

Professor Zhang Fukang of the Shanghai Silicate Institute conducted comparative analyses of Falangcai and Fencai enamels. He found differences in their flux compositions:

Both types contained lead-arsenate, which gave them their characteristic opacity. The color palette of Fencai often borrowed elements from Wucai, such as iron red and green. However, Fencai replaced the transparent iron yellow of Wucai with an opaque yellow. Western chemical analysis identified stannic oxide (氧化锡) in the enamel, while Chinese research suggested antimony oxide (氧化锑) as the colorant.

Among the Falangcai colors, pink stands out as the most distinctive addition to the Fencai palette.

Distinguishing Yangcai from Falangcai produced at the Jingdezhen imperial kiln and the Palace workshop, respectively, remains challenging. Both feature similar opaque enamels. Pieces without transparent Wucai colors and bearing Falangcai-style seal marks are particularly difficult to categorize. Instances of re-labeling between Yangcai and Falangcai occurred during the Qianlong period.

The term Famille rose, coined by Jacquemart in the 19th century, refers to Chinese overglaze enamelled wares dominated by rose pink hues. This term encompasses both Yangcai and Falangcai. Japanese ceramics expert Masahiko Sato even regarded Falangcai as the finest examples of Famille rose.

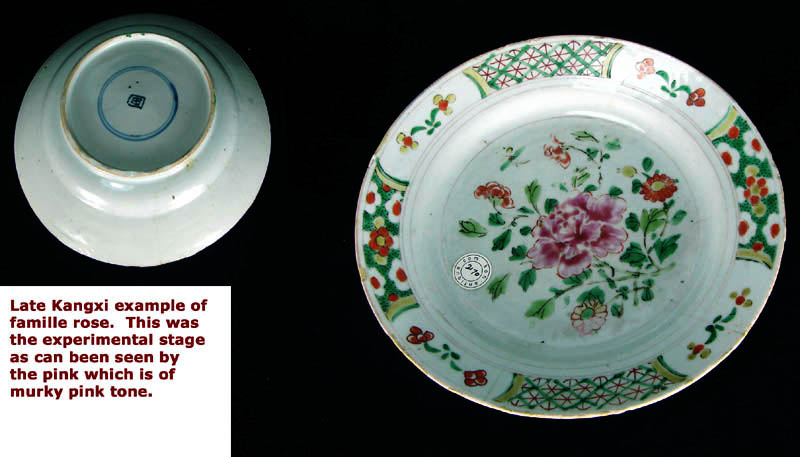

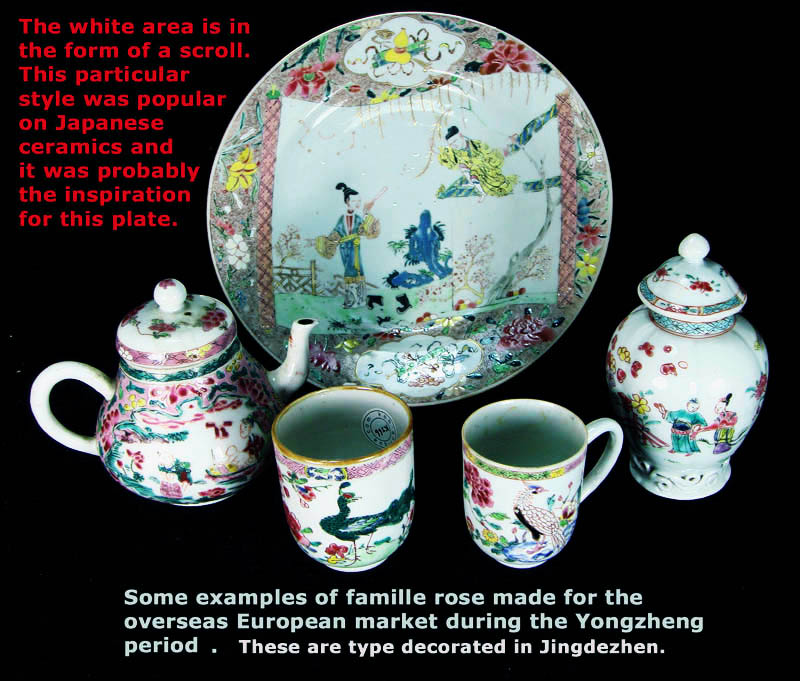

During the late Kangxi period, while the Palace workshop was producing Falangcai wares, the Jingdezhen imperial kiln likely experimented with combining Falangcai and Wucai colors. The finest Yangcai pieces were produced under the supervision of Tang Ying during the Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns.

Interestingly, early export Fencai wares from the Kangxi period were also produced in folk kilns. These pieces used only opaque pink enamel alongside transparent Wucai colors. It remains unclear whether private kiln potters adopted the new technology from the imperial kilns or independently innovated it. European buyers may have influenced these developments by requesting elements of European-style cloisonné decorations. By the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods, export-style Fencai wares were highly sought after in Europe.

The opaque or powdery appearance of Fencai and Falangcai is due to the presence of po li bai (玻璃白), an opaque lead-arsenate white enamel. Shading effects are achieved by varying the ratio of colored enamels to this white enamel.

|

| In this piece, the only fencai enamel is the rose pink colour, the rest are from the wucai palette. Even the yellow is the transparent iron yellow |

Kangxi wucai with similar composition as above

Example showing various fencai opaque enamels

Example showing various Kangxi wucai colours

In the 32nd year of Kangxi's reign, workshops were established in the Yangxin Hall (养心殿) of the palace to produce various crafts, including Falang enamels. Initially, these workshops focused on bronze cloisonné vessels with imported European enamels.

By the 55th year of Kangxi's reign, experiments began with applying Falangcai on porcelain. Plain porcelain vessels from the imperial kiln were decorated and fired in muffle kilns at the Palace workshop. Early attempts faced technical challenges due to differences in the expansion rates of enamels and porcelain, resulting in fine crazing on Kangxi-period Falangcai wares.

Initially, enamels were imported from Europe. By the 6th year of Yongzheng's reign (1728), Chinese artisans successfully produced their own enamels and even introduced new colors.

During the Kangxi period, Falangcai wares often featured colored grounds resembling cloisonné, with red and yellow being particularly favored. Yongzheng-period wares introduced floral, bird, and landscape motifs, often accompanied by poetic inscriptions and seal marks. By the Qianlong reign, European-style human subjects were also depicted.

.

Written by: NK Koh (8 Nov 2013), edited with ChatGPT on 8 Feb 2025.

References

1 中国古陶瓷的科学 - Author 张福康 Published by 上海人民美术出版社