Yuan Blue and White Ceramics

On July 12, 2005, Christie's achieved a record sale when it sold a Yuan blue‐and‐white jar depicting a scene from a Warring States episode—for US $27.7 million. This milestone reflects the dramatic rise in recognition and value of Yuan blue‐and‐white wares, a field that was little known until after 1950.

|

| Yuan jar sold by Christies for record sum of US$27.7 million |

In 1929, RL Hobson briefly mentioned a pair of Yuan vases in the Percival David Foundation, but they attracted little attention at the time. It was not until 1952 that Dr. John Pope undertook the pioneering work of identifying and classifying these wares. Examining pieces in Istanbul’s Topkapi Museum and the Iranian Ardebil Shrine, he noted that the motifs on these vessels bore a striking stylistic resemblance to the famous pair of vases later known as the David Vases.

These vases were originally donated to the Beijing Zhihua (智化) Temple by a devotee named Zhang Wenjin (张文进), who sought blessings for his family. An inscription on the neck of the vases records the date “Zhi Zheng 11th Year” (至正十一年), corresponding to A.D. 1351. Blue‐and‐white wares that share these stylistic characteristics are now commonly referred to as the Zhi Zheng type.

|

|

|

| The David Vase (dated A.D. 1351) exemplifies the refined style later dubbed “Zhi Zheng type”. The original pair of vases was housed at the Beijing Zhihua Temple but was smuggled out of China in 1929 by an overseas Chinese individual and eventually entered the collection of Sir Percival David. | |

In 1974, a pair of qingbai‐glazed, pagoda‐shaped vases with simple floral scrolls—dated to the 6th year of the Yuanyou (元祐) era (A.D. 1319)—was excavated in Hubei. Although initially believed to have been decorated with a grayish cobalt blue, further scientific testing in March 2009 by the Shanghai Museum revealed that these pieces used an iron oxide pigment instead. Because their motifs (such as the peony, plantain leaves, and collar‐shaped cloud on the shoulder) and multi‐layered composition resemble later blue‐and‐white works, Chinese experts classify them as early Yuan blue‐and‐white, now known as the Yuanyou type.

|

|

|

Yuan You Vase

(A.D. 1319) from the Hubei Museum. Initially thought to feature cobalt

decoration, tests have confirmed the use of iron oxide pigment.

|

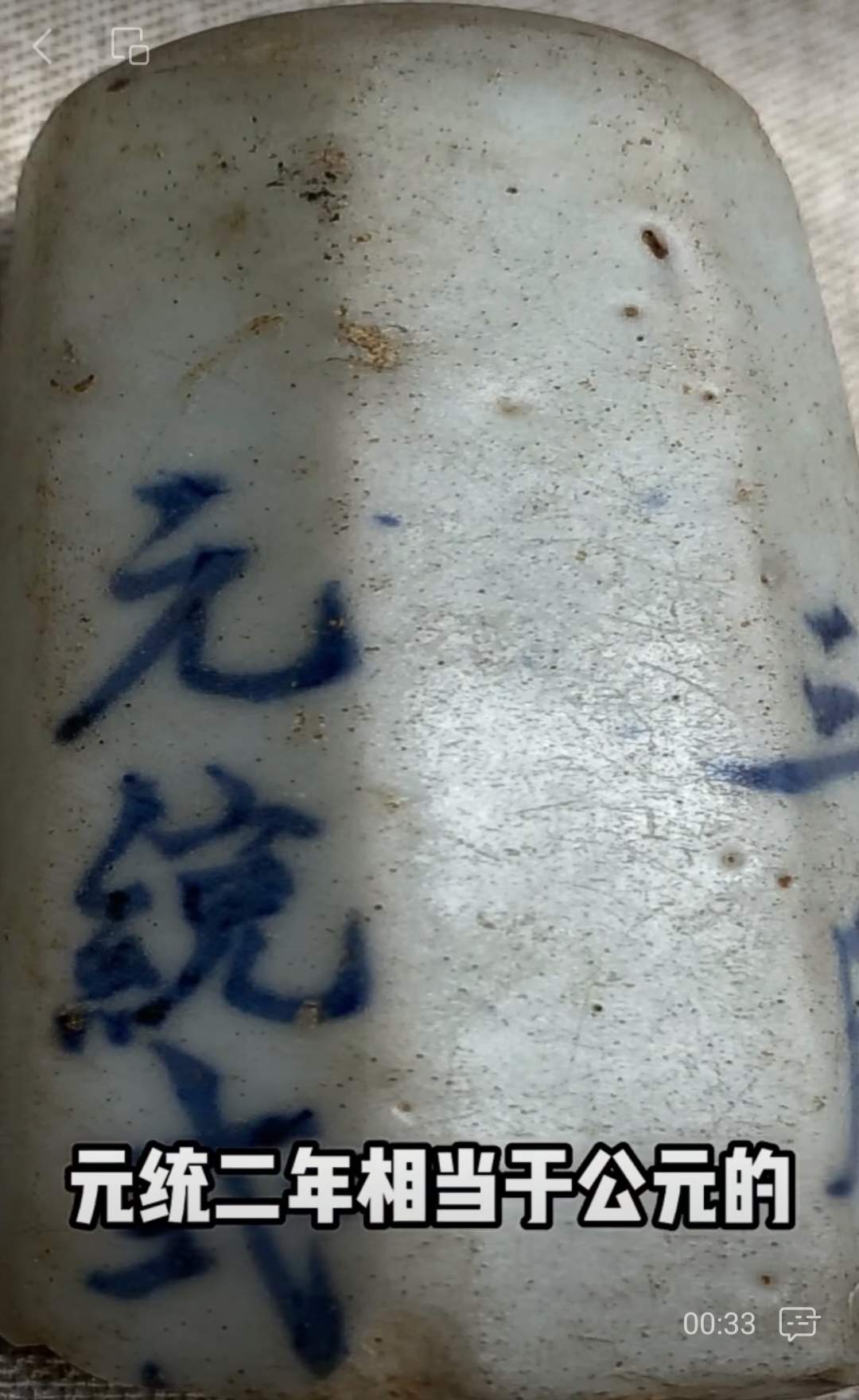

One of the earliest known blue‐and‐white pieces is a pestle inscribed in cobalt blue with the date “Yuantong 2nd Year” (元统二年, A.D. 1334), excavated from Jingdezhen’s Dai Jia Nong (景德镇戴家弄). Another bowl‐shaped vessel bears a date of “Yuantong 3rd Year.”

|

|

| Two of the earliest dated Yuan blue‐and‐white pieces—one marked “Yuantong 2nd Year” and the other “Yuantong 3rd Year.” | |

A fragment bearing a Zhizheng “Jia Shen” date (1344 A.D.) was also discovered in China, and several sherds with cyclical or Zhizheng dates have been unearthed in Jingdezhen—all dating to the 1340s.

|

| Inscription on David vase and the fragment with Jia Sheng cyclical date. |

At the Xuzhan Tang Museum (徐展堂艺术馆), a large Zhizheng‐type charger decorated with vegetal and floral motifs arranged in circular bands bears a faint inscription (visible under ultraviolet light) reading “Zhizheng 4th Year” (至正四年, A.D. 1343). Taken together, the archaeological and textual evidence suggests that the production of Yuan blue‐and‐white wares most likely began around A.D. 1330.

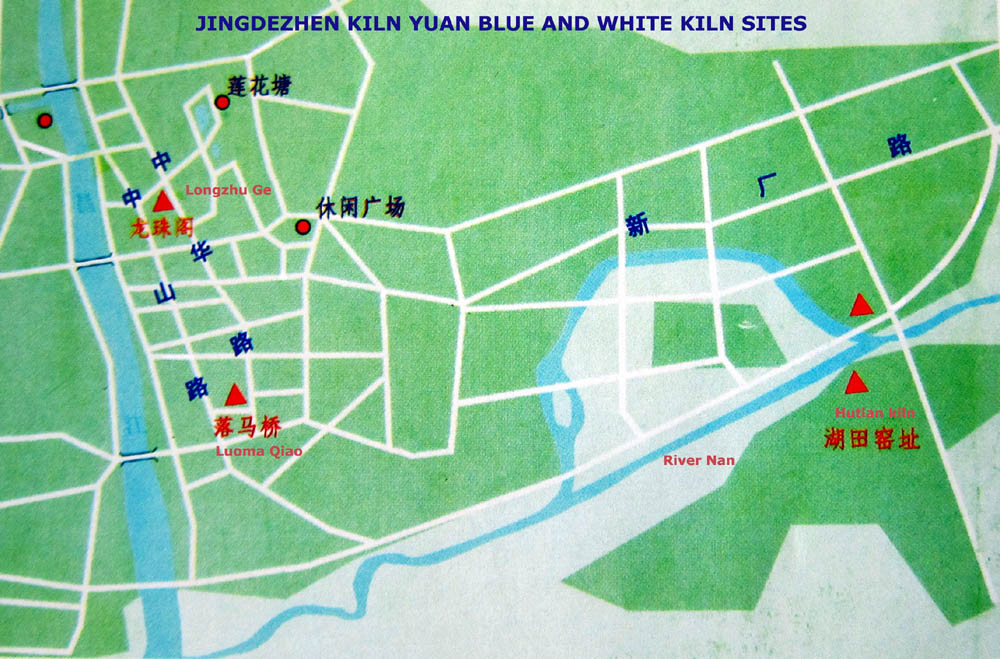

Kiln sites producing Yuan blue‐and‐white wares have been identified in both Jingdezhen and Hutian. In Hutian, sites south of the Nan River specialized in producing large vessels—such as plates, jars, and vases with multi‐layered motifs—primarily destined for Middle Eastern markets. In contrast, kiln sites north of the river produced smaller vessels (jarlets, bowls, and dishes with simpler motifs) that were exported to Southeast Asia.

Between 2002 and 2003, the Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology conducted an excavation at the Hutian Kiln site on the southern bank of the Nanhe River in Jingdezhen, uncovering a Yuan Dynasty dragon kiln. The kiln remains measure 22 meters in length and 3.4 meters in width, with both the kiln head and tail partially damaged. On both sides of the kiln walls, protective barriers were constructed using fragments of saggars. This was the first Yuan Dynasty dragon kiln to be excavated at the Hutian Kiln site and is also the best-preserved Yuan blue-and-white dragon kiln in China to date.

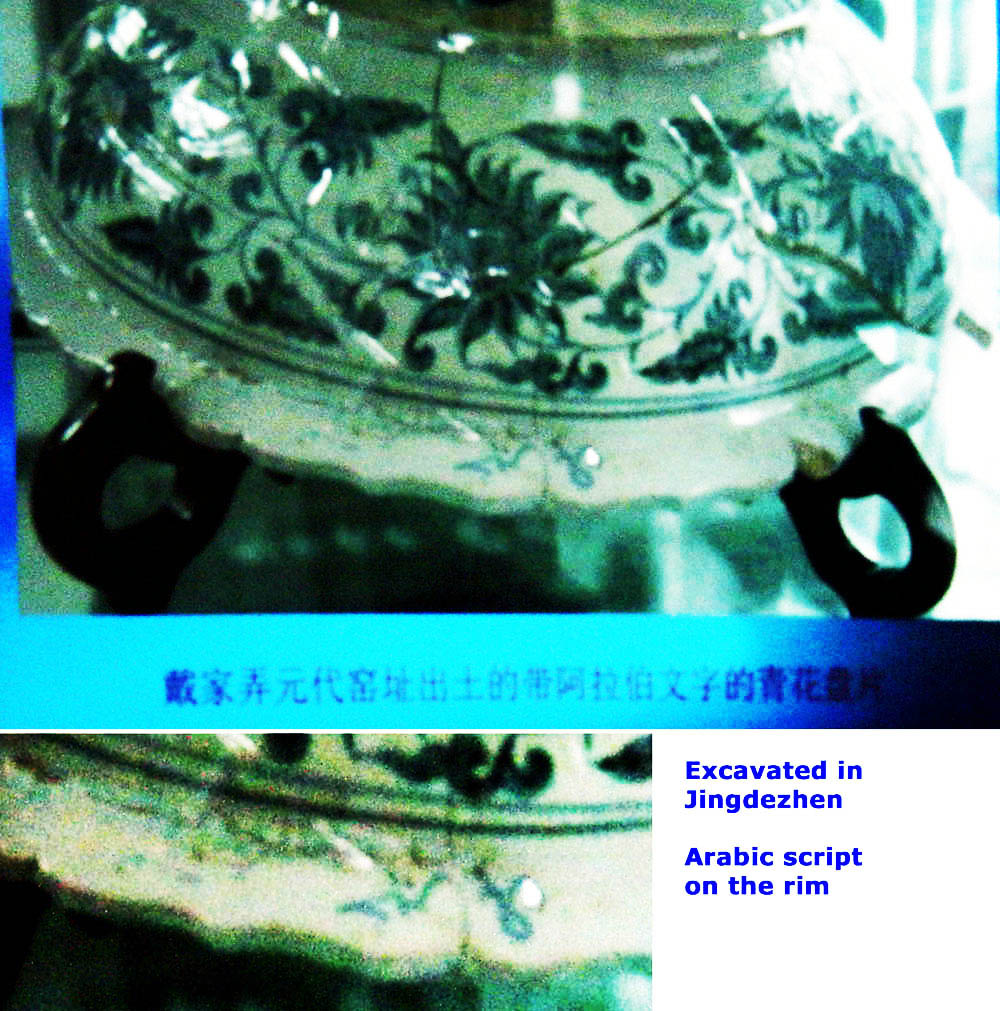

During the excavation, a significant number of Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white porcelain fragments were unearthed from the kiln site and associated waste pits. These blue-and-white porcelains coexisted with other varieties, such as egg-white glaze and underglaze red porcelains. The porcelain fragments feature a dense and durable body with a fine texture, occasionally showing small pores. Their shapes include bowls, plates, cups, and boxes. The primary motifs consist of pond mandarin ducks, intertwined chrysanthemum, camellia, pine-bamboo-plum (Three Friends of Winter), intertwined peony, and intertwined lotus. The bases of bowls and plates are left unglazed. The unearthed blue-and-white porcelains exhibit two distinct styles: blue-ground white patterns and white-ground blue patterns, with some pieces displaying typical Islamic artistic influences.

The excavation report classifies these Yuan blue-and-white porcelain artifacts into two categories: the "Istanbul Type" and the "Philippines Type." It also suggests that this site may have been one of the kilns associated with the Fuliang Porcelain Bureau.

|

| Map showing the distribution of kilns in Jingdezhen and Hutian |

|

|

|

|

|

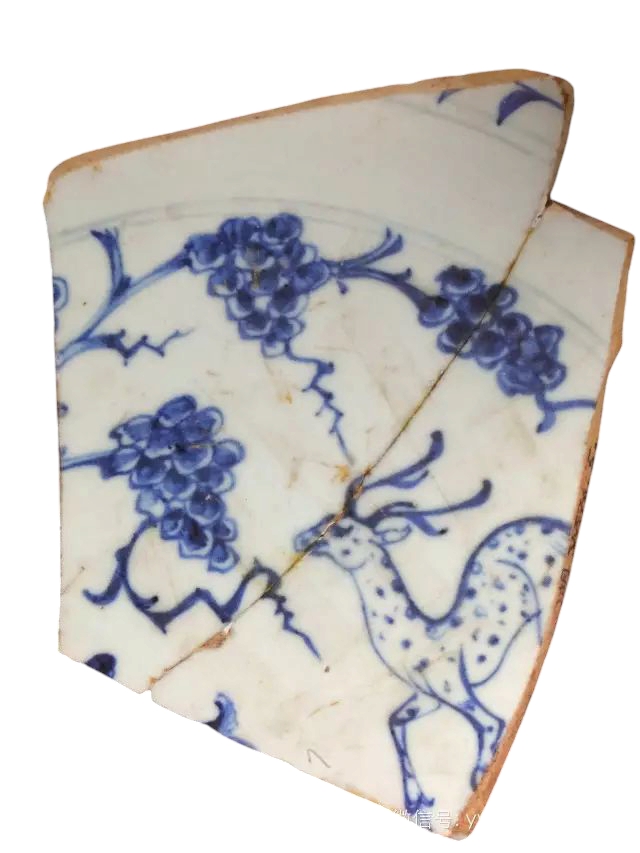

| High quality Yuan blue and white from Hutian kiln sites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

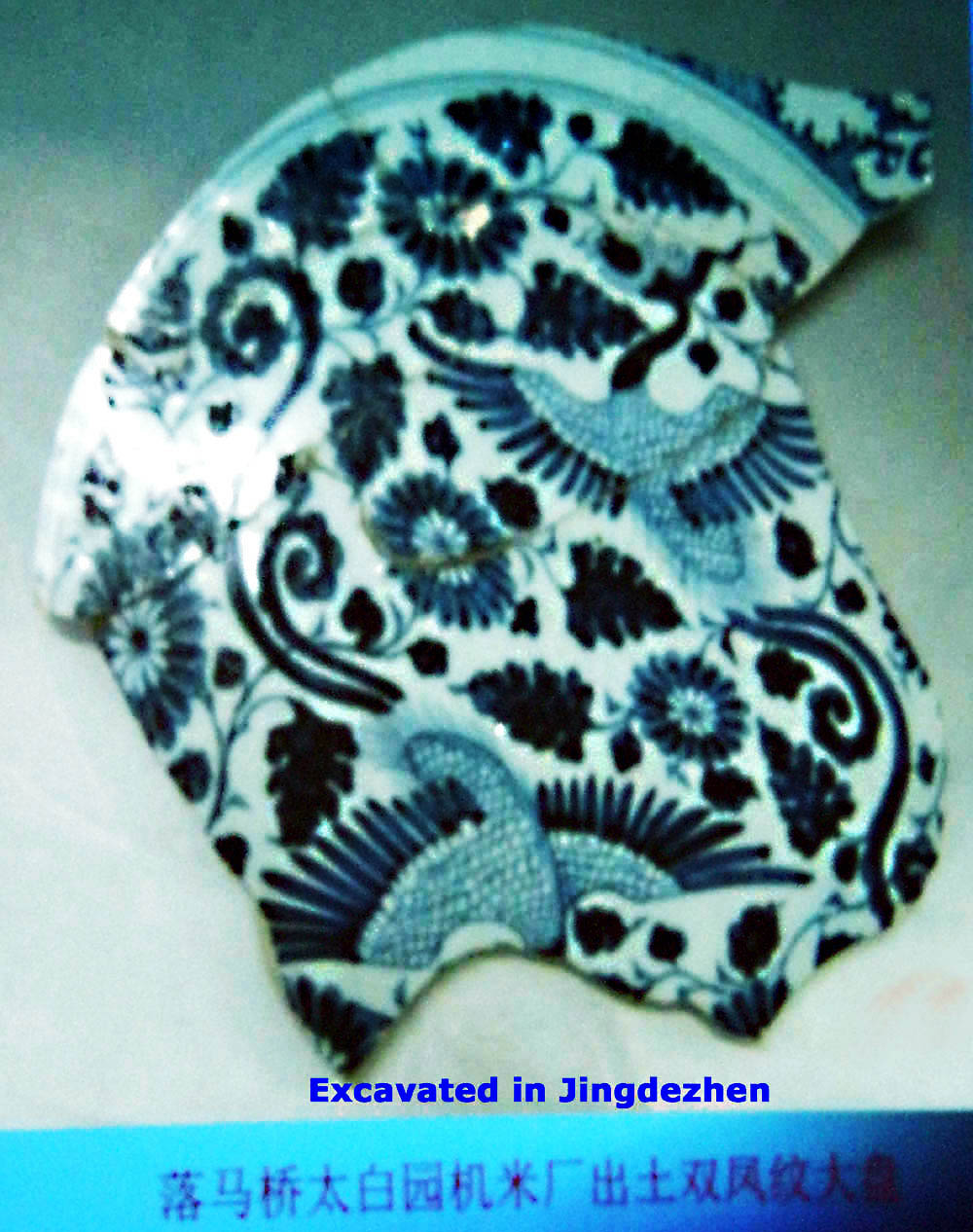

| Fragments recovered from Jingdezhen’s Luoma Qiao site. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High‐quality fragments exhibited at Jingdezhen Taoci University.

|

The Zhushan kiln site specialized in producing vessels for the palace, such as

cover jars and weiqi boxes. Notably, dragons decorated on these jars feature

five claws—a design element traditionally reserved for imperial use. Some pieces

from Zhushan were glazed in blue or turquoise and accented with gold motifs.

According to the Yuan text Yuan Dianzhang (元典章), the use of gold gilding was

forbidden for commoners. (Recent scholarly debate, however, suggests that the

five‐clawed dragon motif may have been introduced during the Hongwu period,

raising questions about the quality differences between imperial and export

wares.)

|

|

|

| Vessels featuring a five‐clawed dragon from the Zhushan kiln site |

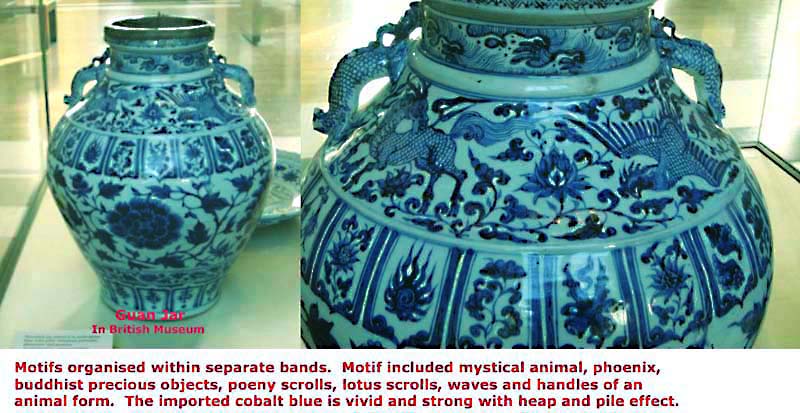

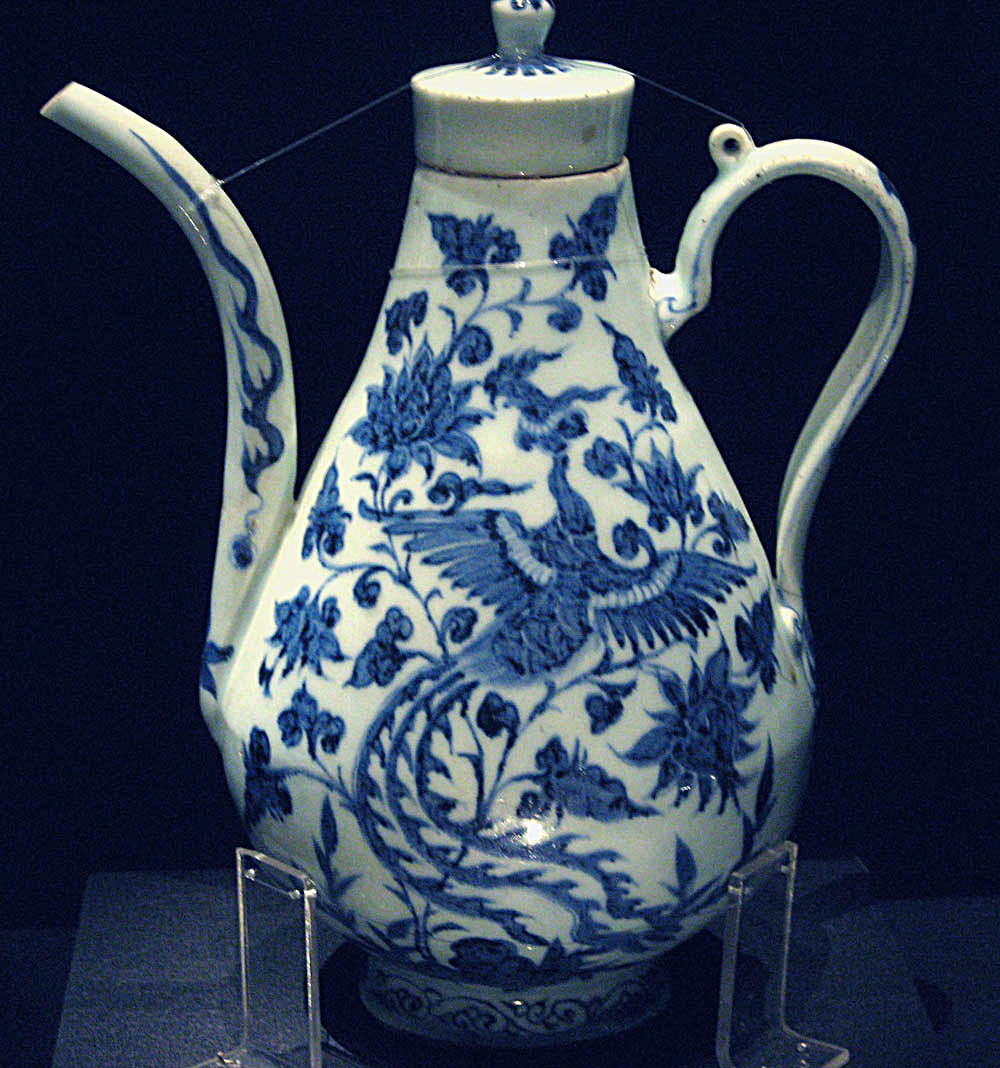

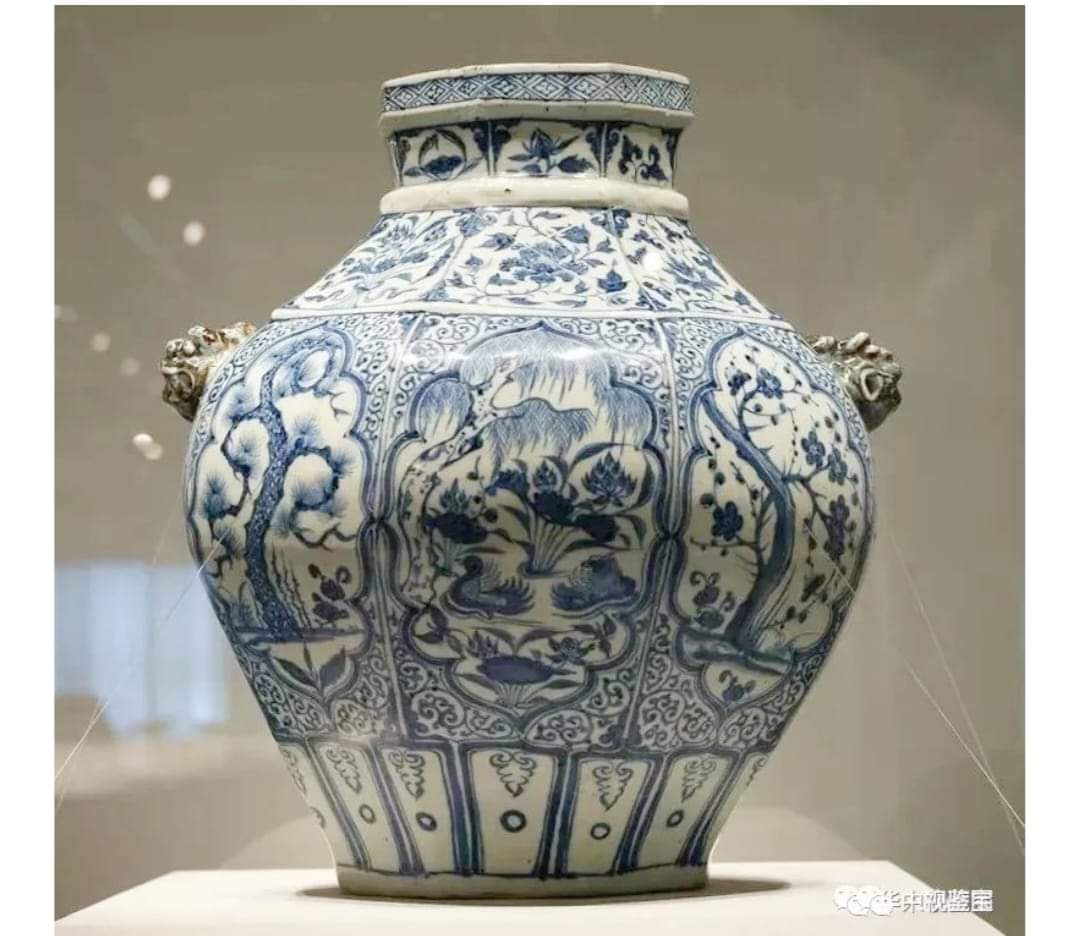

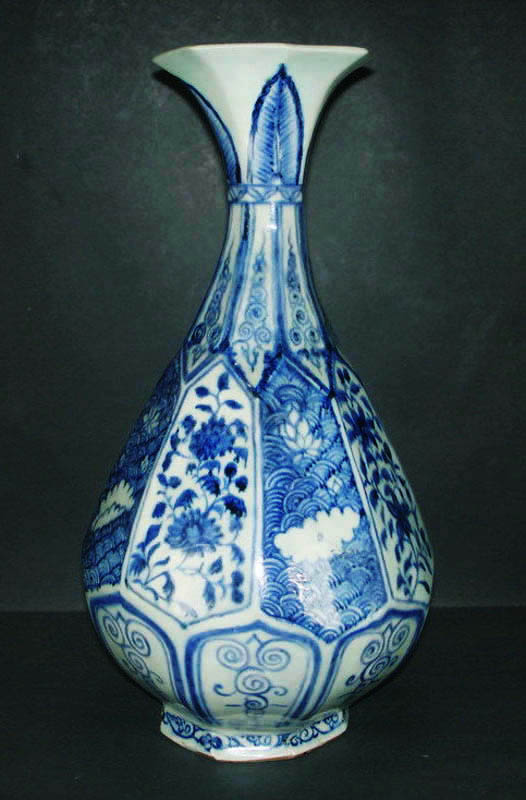

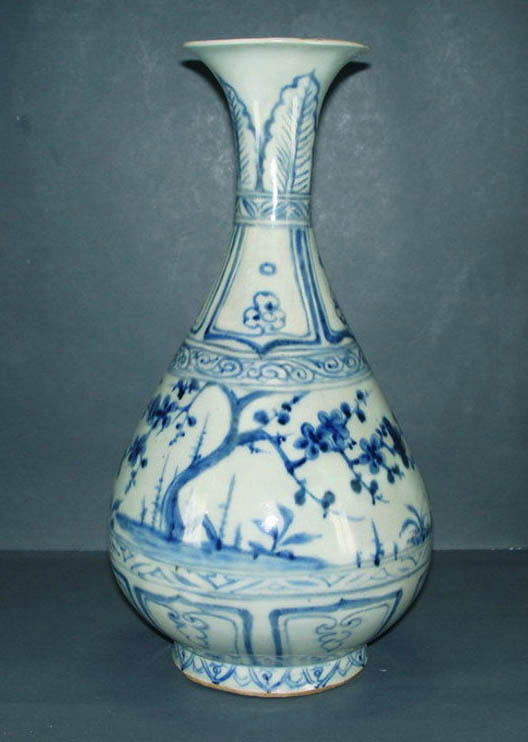

The most exquisite Yuan blue‐and‐white wares include large plates, guan jars, rectangular flat vases, meiping/yuhuchun/gourd‐shaped vases, and large bowls. The finest collections are housed in institutions such as the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul and the Ardebil and Bustan collections in Tehran. These high‐quality pieces, exemplified by the David Vase, are known as the Zhizheng type. They are characterized by the sophisticated organization of multiple motifs arranged in distinct bands (the David Vase, for example, features eight bands) and a transparent glaze with a subtle blue tint—qualities that set them apart from the simpler qingbai or shufu‐glazed pieces produced for Southeast Asian markets.

The range of motifs is extensive, including:

Floral and plant motifs: Various flowers, floral scrolls, peonies, and plantain leaves.

Animal and mythological figures: Dragons, phoenixes, cranes, herons, mandarin ducks, fish, and other mystical creatures.

Cultural and historical scenes: Representations of Buddhist symbols, clouds, waves, human figures, and scenes from ancient episodes (e.g., events from the Three Kingdoms or Han Dynasty).

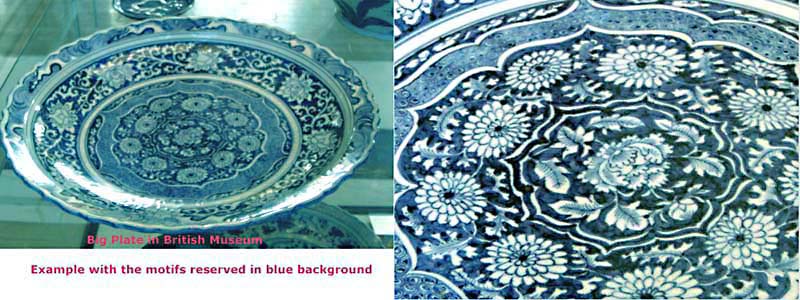

Although the use of bands to organize motifs is a technique seen in earlier wares (such as Song Cizhou ceramics), Yuan blue‐and‐white pieces are remarkable for how the potters managed to integrate a multitude of motifs into a single, coherent composition. In some cases, motifs are rendered against a blue background, and the inclusion of “cloud collars” (seen on the shoulder of the early Yuan Yuanyou vase) provides a distinctive, refreshing element.

|

|

| Two examples from the British Museum depicting the "Zhi Zheng" style sophisticated organization of multiple motifs arranged in distinct bands. |

|

|

|

| Big plate, an ewer and a jar from the Beijing Palace Museum |

|

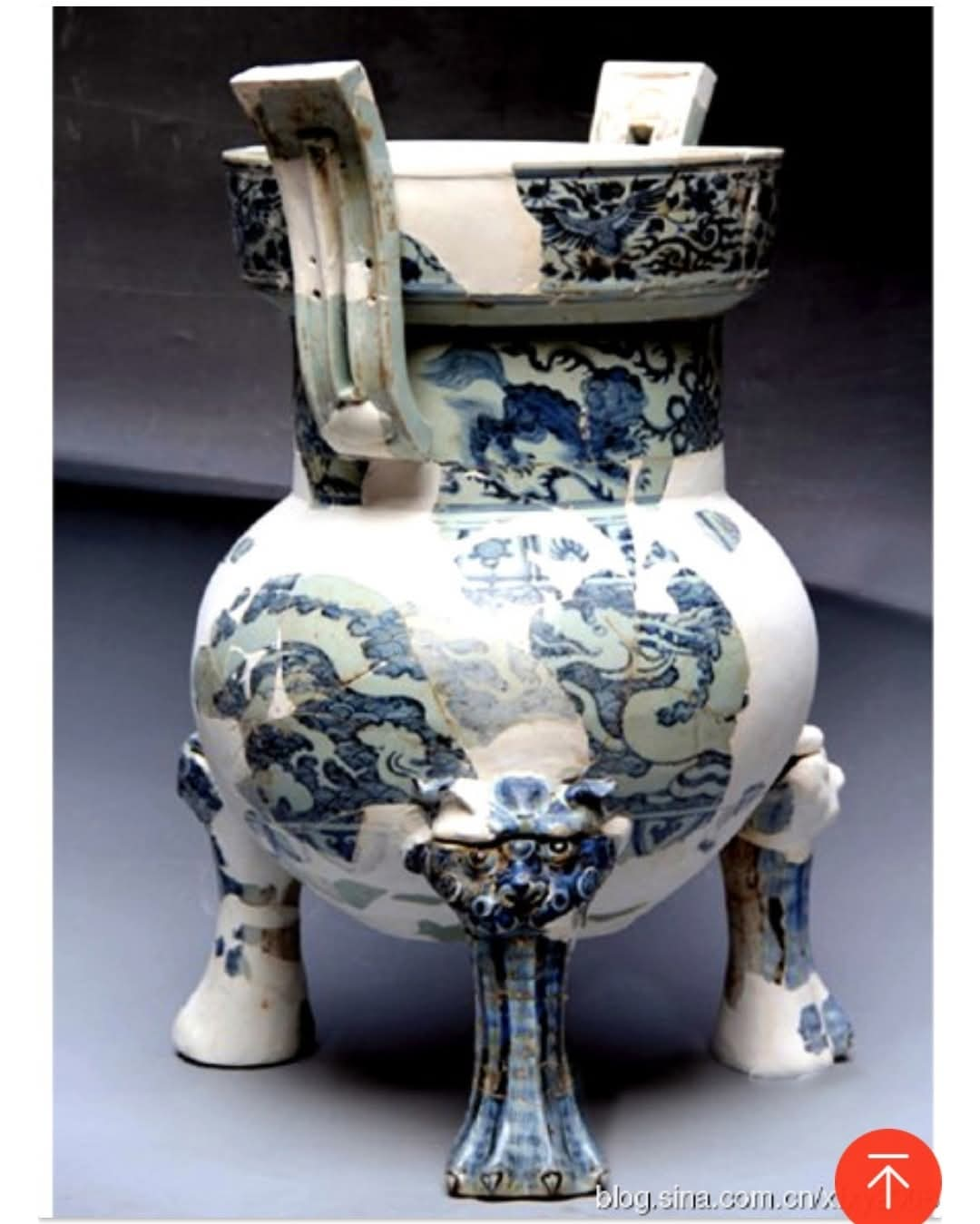

| A gigantic Yuan blue and white incense burner with dragon motif found in a Zhenjiang site |

|

|

|

| A human motif vase in Huebei Museum | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

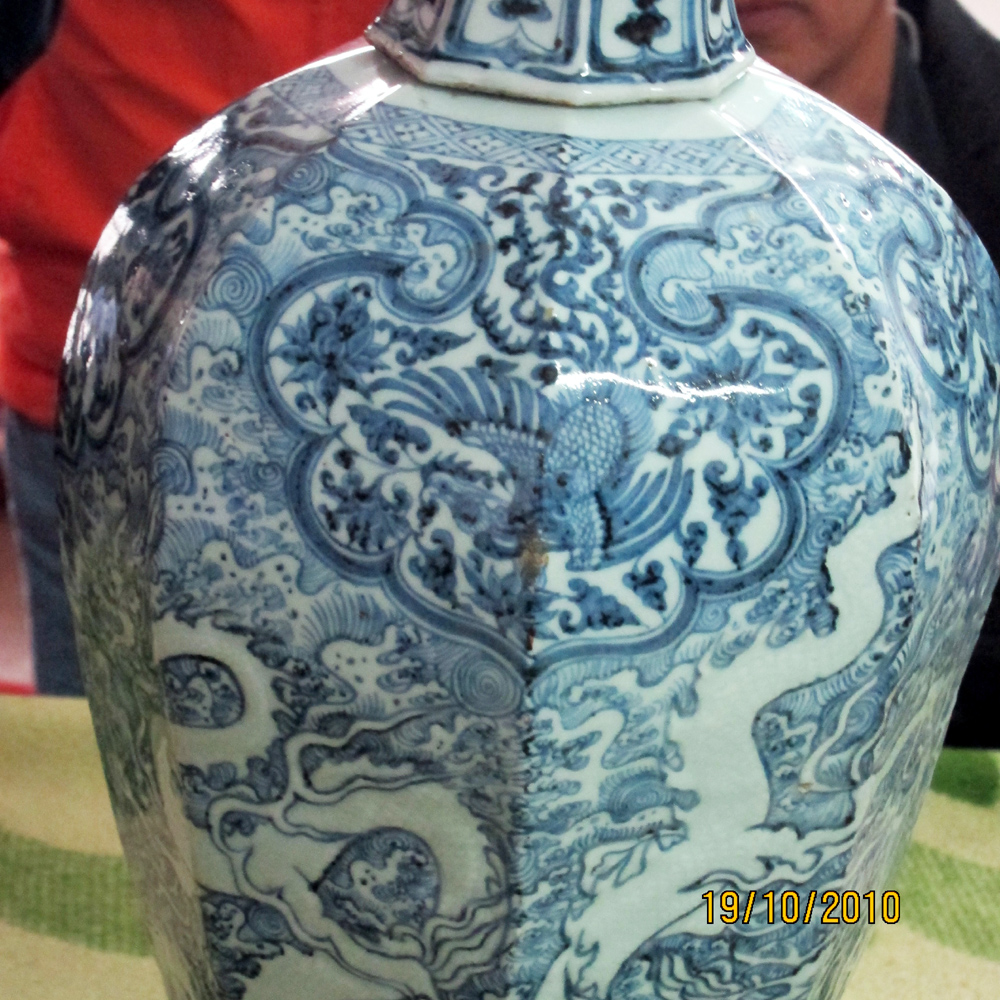

| A Yuhuchun Vase with lion playing embroidered ball and Lidded Meiping with dragon motif in Hebei Museum. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Three large Yuan blue‐and‐white plates in the National Museum of Indonesia. |

|

|

| Two similar octagonal jars—one found in China and the other in Thailand—demonstrating the international distribution of these wares | |

|

| Yuan blue and white porcelains found at Firozshah Kotla complex at Delhi, India. |

In addition to these high‐quality items, many smaller vessels (such as ewers, jarlets, cups, and bowls with qingbai or shufu glazes) have been excavated in Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines and Indonesia. These simpler designs typically feature calligraphic floral or cloud motifs rendered in a greyish cobalt blue and were produced at kiln sites such as Hutian (south of the Nan River).

|

| Lower quality utilitarian vessels were produced in Hutian kiln located South of River Nan |

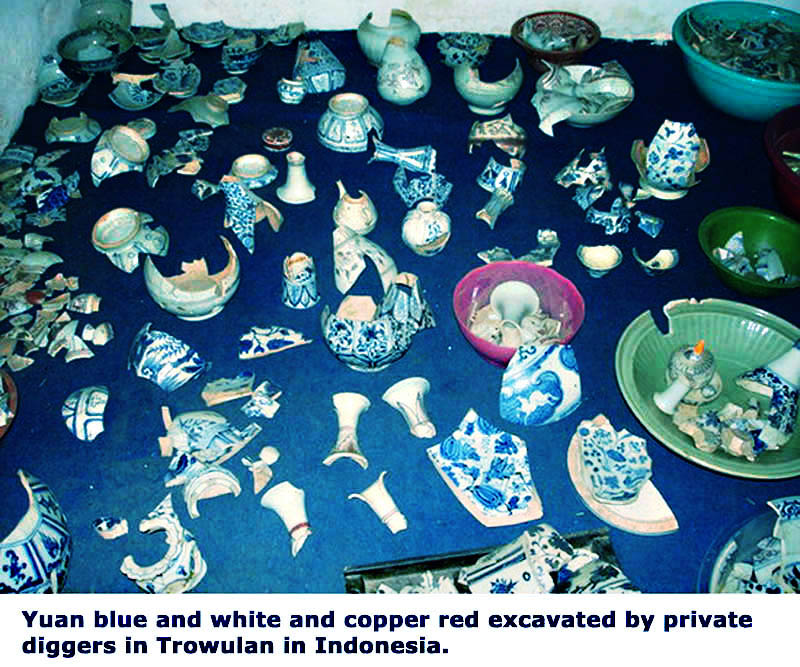

It is important to note that while blue‐and‐white wares exported to the Middle East are widely recognized for their high quality, those destined for Southeast Asia are not necessarily inferior. Excavations at Trowulan—the former capital of the Majapahit Empire in Java—have uncovered many high‐quality pieces, including vases and large jars.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Good quality Yuan blue ad white wares found in Trowulan—the former capital of the Majapahit Empire in Java | |

During the Hongwu period, blue‐and‐white wares were produced exclusively for the palace. Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang’s ban on foreign trade cut off the supply of imported cobalt, likely leading the palace to monopolize the remaining cobalt sources. Nevertheless, during the transitional period from the Yuan to the Ming dynasty, folk kilns continued to produce blue‐and‐white wares for a short period. In Jingdezhen, several stem cups decorated with simple human figures and floral motifs have been excavated, showing stylistic evolution from the classic Yuan designs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yuan/Hongwu blue‐and‐white stem cups. | |

|

|

|

|

| Hongwu bowl with impressed blue‐and‐white dragon decoration. | |

At first glance, it appears that two types of cobalt were used in decorating Yuan blue‐and‐white wares. The high‐quality pieces display a strong, vibrant blue, while the smaller items often show a greyish tone. Traditionally, it has been assumed that the brilliant blue resulted from imported cobalt, whereas the greyish tones came from local sources.

|

| A group of blue and white samples with different shade of blue |

Scientific analysis reveals that local cobalt is high in manganese and low in iron oxide, which is believed to contribute to the greyish hue. In contrast, imported cobalt is high in iron oxide and low in manganese. However, recent tests have consistently shown that even the greyish blue tones were produced using imported cobalt—suggesting that factors such as firing temperature, kiln atmosphere, and the overall quality of the cobalt also play significant roles.

The imported cobalt is known in Chinese as sumali (苏麻离青) or suboni (苏渤泥青), and some scholars have suggested that its source may be Kashan in Iran or Samarra in Iraq. Jingdezhen potters refined their methods through extensive test firings, as evidenced by numerous sampler pieces recovered from kiln sites.

|

|

| Sampler pieces used to assess cobalt quality. |

It is possible that potters experimented with blending different grades of cobalt to achieve varied visual effects. For example, one piece shows a brilliant blue applied to floral scrolls on the belly contrasted with a darker blue used for classic scrolls and lotus bands. Overall, however, such experiments met with limited success.

|

| An example which shows a more brilliant blue used for the floral scrolls on the belly and a more darkish blue for the classic scrolls and lotus bands |

Some vessels also feature a combination of underglaze blue and copper red decoration. A notable example is a guan jar in the Hebei Museum collection. This piece includes decorative elements such as trailed slip beaded lines and molded relief details that create an openwork effect—a style popular during the Yuan period and seen on many Qingbai guan jars and Yuhuchun vases.

|

|

| Jar with combined underglaze blue and copper red decoration found in Hebei Baoding.. | |

Concluding Remarks

The use of cobalt blue for porcelain decoration was first experimented with during the Tang Dynasty. These early products were primarily intended for the Middle Eastern market. Three precious dishes with floral motifs were recovered from the Belitung shipwreck, highlighting this early decorative style. However, efforts to further develop this form were subsequently abandoned and only resumed during the late Yuan period, around 1330.

As a decorative art form, blue and white porcelain reached remarkable levels of sophistication and artistic achievement. Despite its visual appeal, early production mainly targeted overseas markets. It was during the Ming Dynasty that blue and white wares gained Imperial patronage, with Jingdezhen's imperial kilns tasked with producing them for palace use.

By the mid-15th century, Jingdezhen's folk kilns were also producing these wares in large quantities for both domestic and international markets. Over time, blue and white porcelain became one of the most iconic decorative styles, with its timeless appeal enduring to this day.

Written by NK Koh (15 Dec 2009; updated 18 Feb 2012 ,13 Mar 2024) and 8 Feb 2025.