Fujian and Longquan Trade Ceramics in the Jepara Shipwreck

Discovery and Initial Findings

In the early 2000s, a significant number of celadon and white wares began appearing in the Jakarta antique market. Sellers claimed these artifacts originated from a shipwreck located approximately 34 km offshore from Jepara. Unfortunately, the government did not take immediate action to prevent looting.

The wreck site was peculiar, strewn with large boulders. Among the recovered artifacts was a stone anchor measuring about 2.5 meters in length. A similar anchor is displayed at the Maritime Museum in Quanzhou, suggesting the ship may have been a Chinese junk.

The ship is believed to have sunk as early as A.D. 1130. The latest copper coins initially observed at the site were from the Zhonghe period (which ended in A.D. 1118). However, I have personally seen later coins—purportedly from this wreck—dating to the Jianyan period (which ended in A.D. 1130). Based on further analysis, I believe the shipwreck may date later than A.D. 1130, possibly around A.D. 1150–1175. I will elaborate on this reasoning below.

|

||

Additional Research and Findings

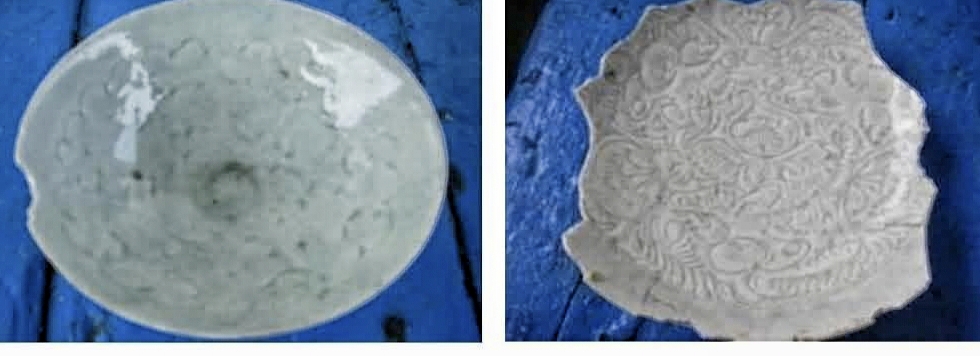

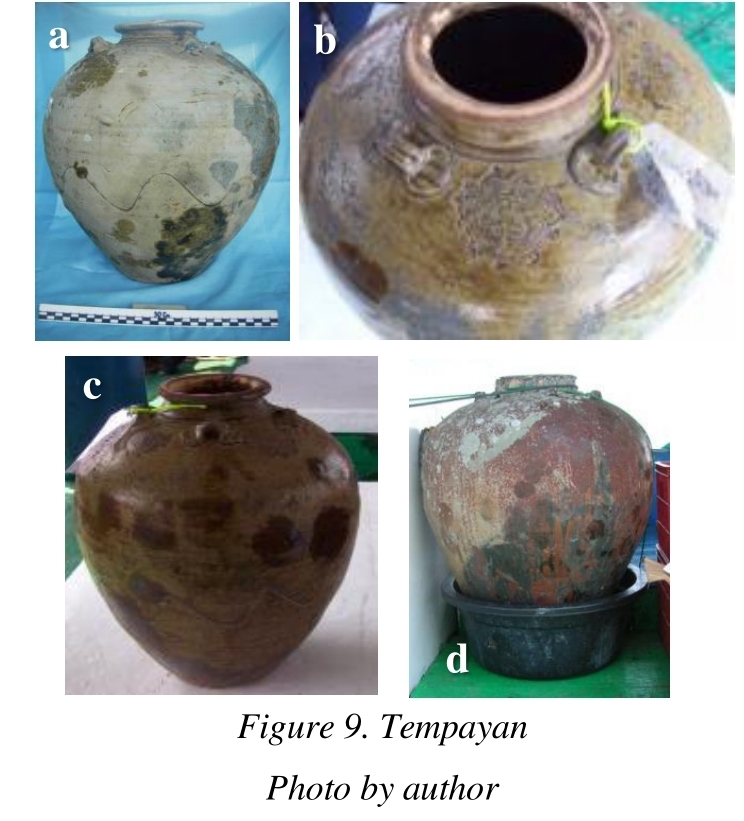

In 2007, Jujun Kurniawan participated in salvaging the Jepara wreck, though by then it had already been heavily looted. Despite this, valuable information was recovered. As with other 12th-century wrecks, a small quantity of Jingdezhen qingbai wares was present. Also recovered were some brown glaze Nanhai Qishi storage jars which were common presence in Northern and Southern Song wrecks.

|

| Two Jingdezhen Qingbai bowl, one with carved absract waves and the other infants among foliage (Photo Credit: Jujun Kurniawan) |

|

| Guangdong Qishi kiln brown glaze jars from the Jepara wreck are similar to those found in the Huaguang Jiao 1, Java Sea and Nanhai 1 wrecks (Photo credit: Jujun Kurniawan). |

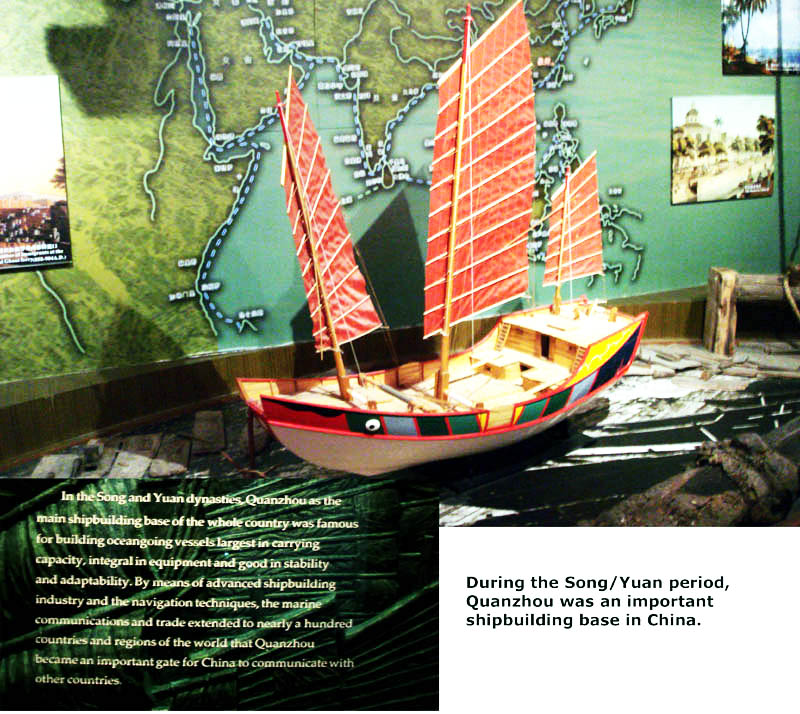

Rise of Quanzhou Port and Fujian Trade Ceramics

Quanzhou, in Fujian Province, was a major trading hub known to Marco Polo as Zayton and was the largest seaport in Asia during the Song and Yuan periods. Many regions along the Fujian coast leveraged their proximity to Quanzhou to produce export ceramics. The most commonly traded ceramics were green wares (celadon), white wares (qingbai), and black/brown wares.

Zhao Rugua’s Zhufanzhi (c. A.D. 1225) lists 46 countries as trading partners of China, including Annam, Cambodia, Srivijaya, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Java, the Eastern Indies, the Philippines, and even Zanzibar. The Yuan-period Daoyi Zhilue by Wang Dayan expands this list to at least 58 countries.

A map in the Quanzhou Museum illustrates the maritime trade routes originating from Quanzhou. Although Jepara lies along one of these routes, it remains unclear whether it was the intended destination of the ship that sank offshore.

Ceramics in the Jepara Wreck

The ceramics cargo consisted mainly of Fujian green, white, and brown-glazed wares, along with Longquan celadon, a small number of Jingdezhen Qingbai wares and also Guangdong Nanhai kiln brown glaze storage jars.

Fujian and Longquan Greenware (Celadon)

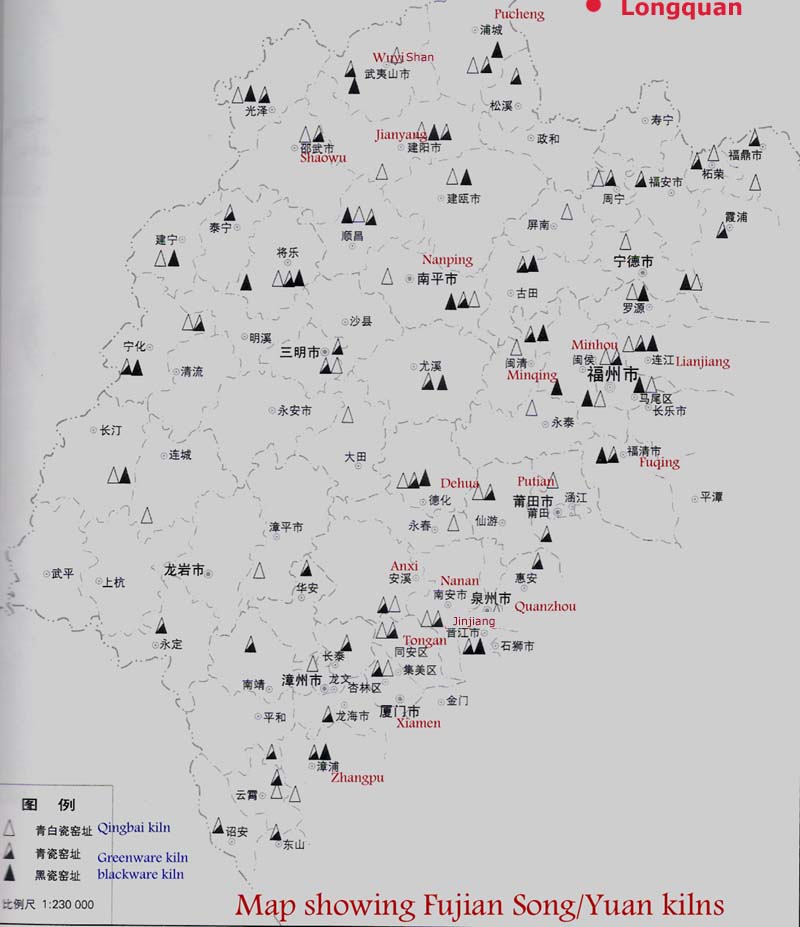

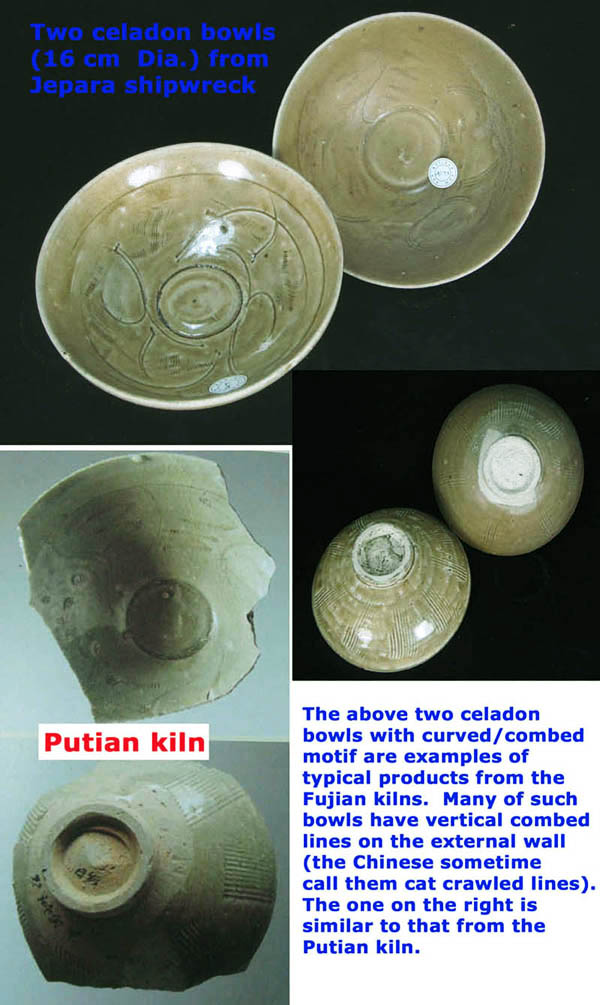

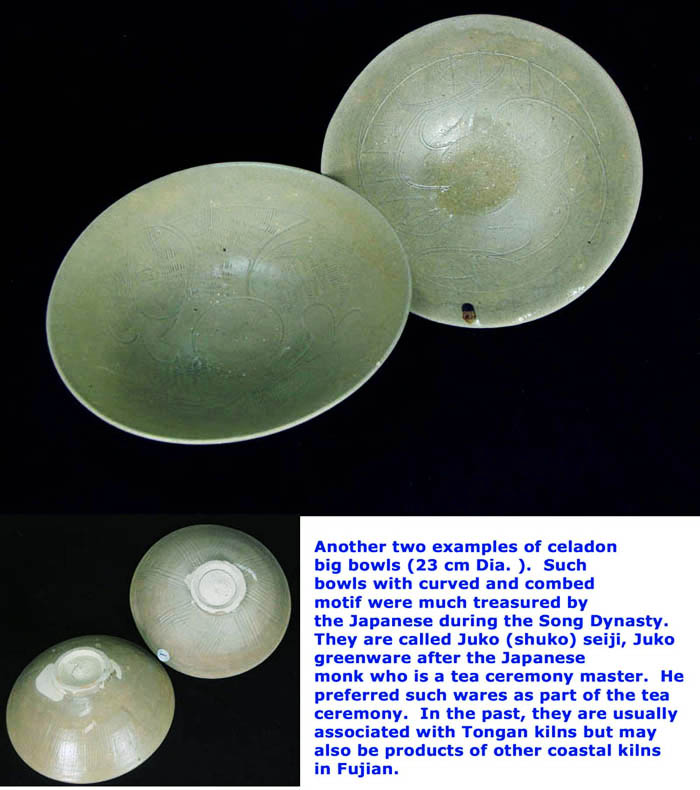

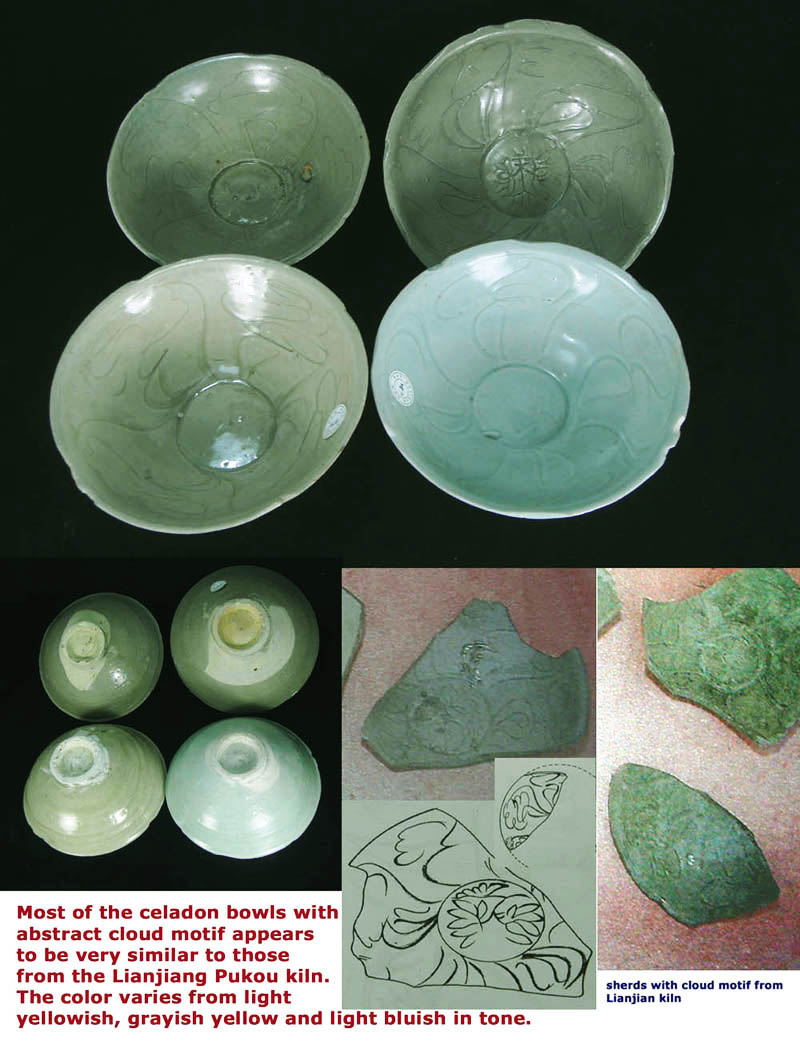

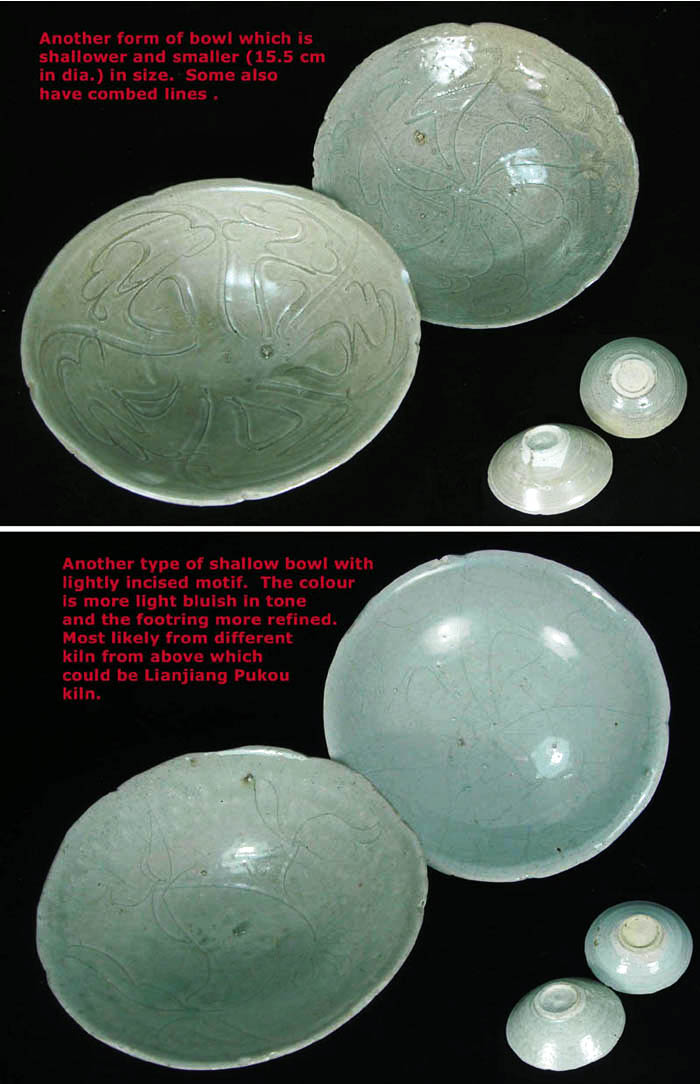

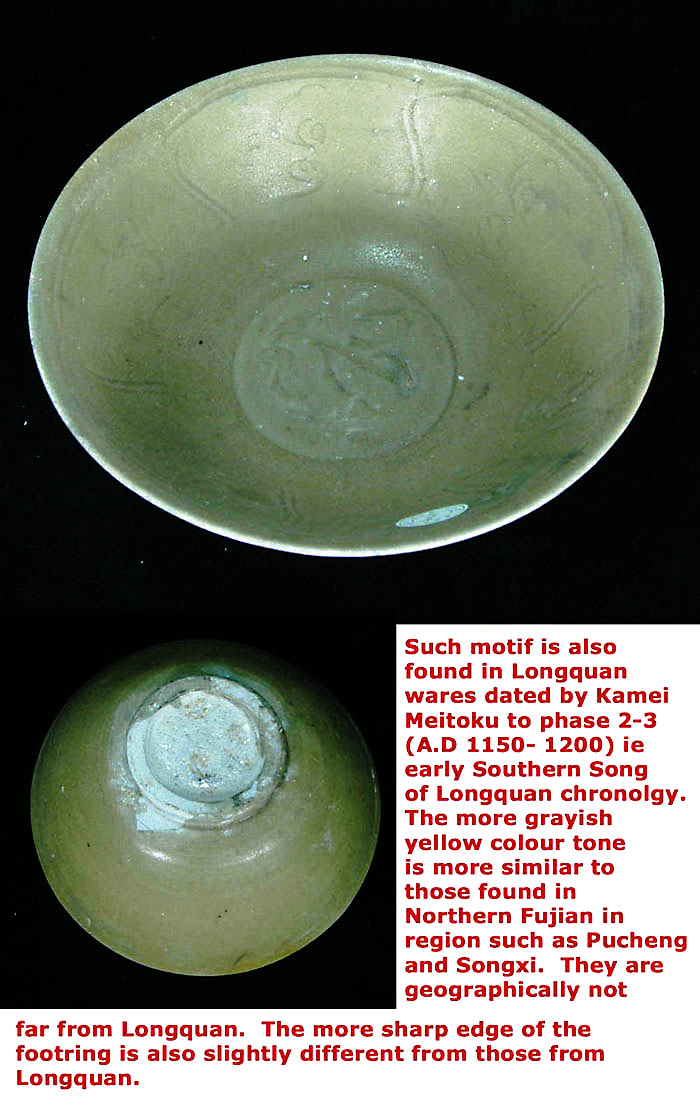

The wreck contained both large and small celadon bowls featuring carved, combed, or dotted decorations on the interior. The exterior is either left plain or decorated with vertical combed lines. By the Southern Song Period, Longquan ceased using combed lines on the exterior, but Fujian carried on for a couple of decades.The color tones of these Fujian wares range from olive green to grayish green, with varying degrees of yellow. Compared with the Longquan version, the Fujian pieces are less refined; in most cases the outer lower portion of the bowls is left unglazed (whereas in the Longquan version only the outer base is unglazed).

This style, commonly referred to as “Tongan type” or “Juko (shuko seiji)” greenware, represents a continuation of the Longquan tradition. Longquan kilns began producing such wares during the mid-to-late Northern Song period. According to Kamei Meitoku’s article Chronology of Longquan Wares of the Song and Yuan Periods, these wares date to the early 12th century. However, findings from the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck (A.D. 1162) indicate that the Fujian version continued to be produced at least until A.D. 1175.

The primary production center for these wares in southern Fujian was Nan’an (南安), which housed more than 47 kilns. Other notable kilns were in Tong’an (同安), Anxi (安溪), Xiamen (厦门), Minhou (闽侯), Fuqing (福清), Putian (莆田), and Lianjiang (连江).

The Longquan celadon bowls from this wreck are generally of poorer quality compared to those produced in the main production centre of Dayao and Jincun (大窑和金村)。 They are likely products of the kilns in Longquan eastern region such as in Da Baian, Anren or Anfu (大白岸,安仁或安富)

Examples of Fujian Celadon Wares Found in the Wreck

|

| Example from the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck featuring a Chinese “Ji” (吉) character—a product of a Fujian Tongan/Nan’an kiln. Similar type found in the Jepara wreck. |

|

|

|

|

| Small green glaze bowl (diameter 12.5 cm) with an abstract carved decoration on the cavetto. Similar bowls have been found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 and Java Sea wrecks |

Fujian green glaze plates with carved floral decoration (Photo credit: Walter Kassela)

Examples of Longquan Celadon Wares Found in the Wreck

|

|

|

| Longquan celadon bowl with carved lotus decoration. |

|

|

Large celadon bowls decorated with wild goose and floral scroll motifs. These have been attributed to the Anfu kiln in Longquan, as noted in the book “Ceramics from Tioman Island,” based on an archaeological report from China. |

White (Qingbai) Wares

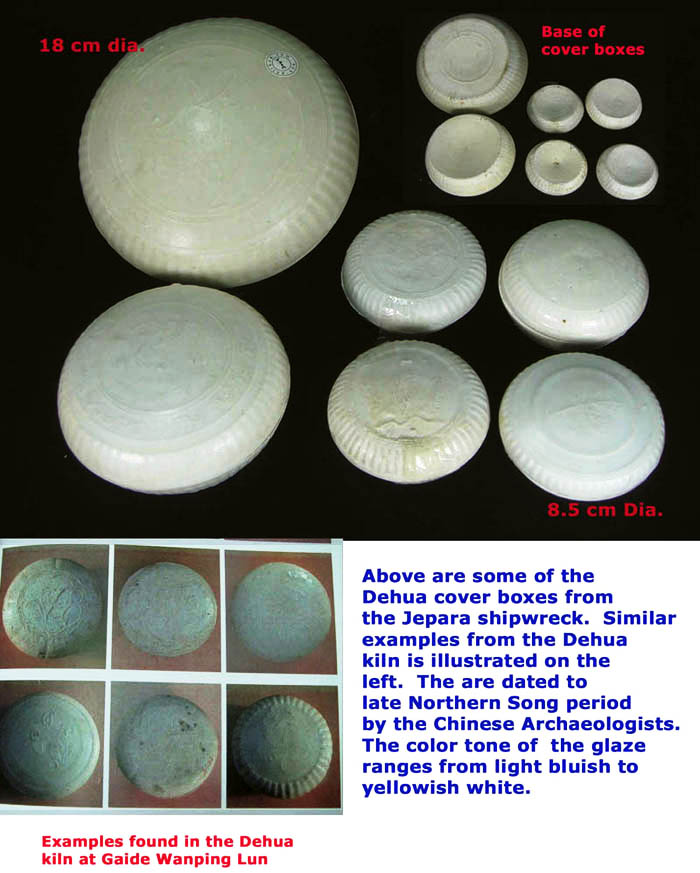

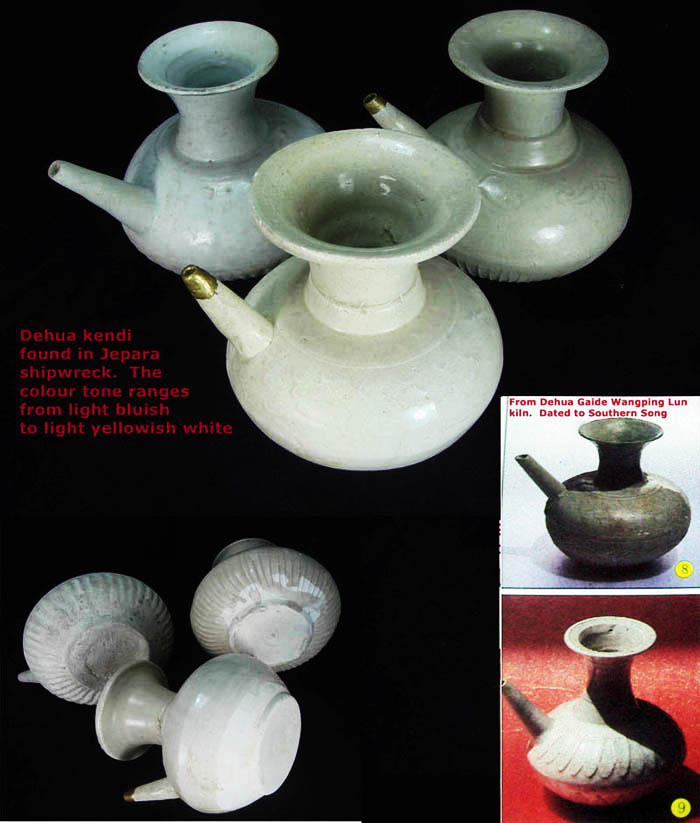

The Jepara wreck contained a substantial quantity of white (qingbai) wares, mainly from the Wanpinglun (盖德碗坪崙) kiln, including:

- Covered boxes: Plain or featuring impressed floral motifs.

- Large bowls: Plain or featuring carved/combed abstract motifs.

- Kendīs: Impressed floral or abstract motifs.

- Vases: Floral-shaped mouth vases, both plain and with impressed floral decoration.

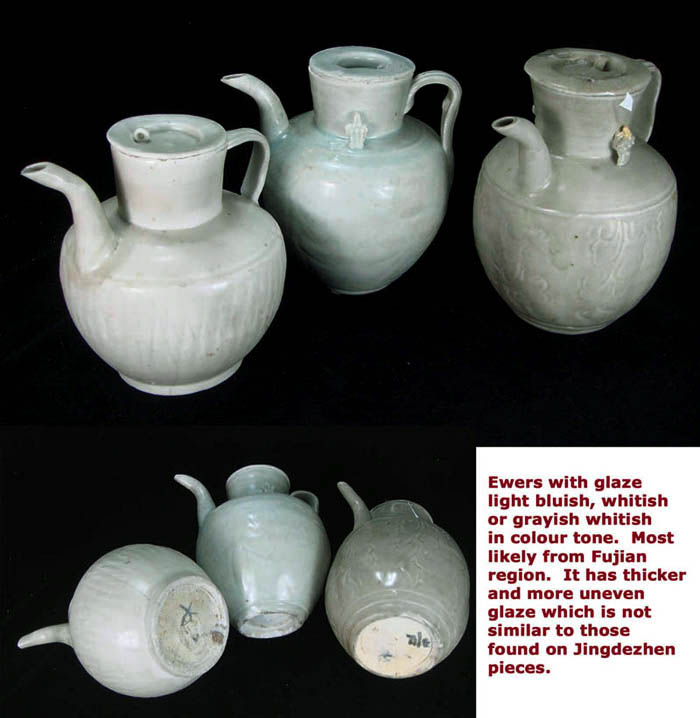

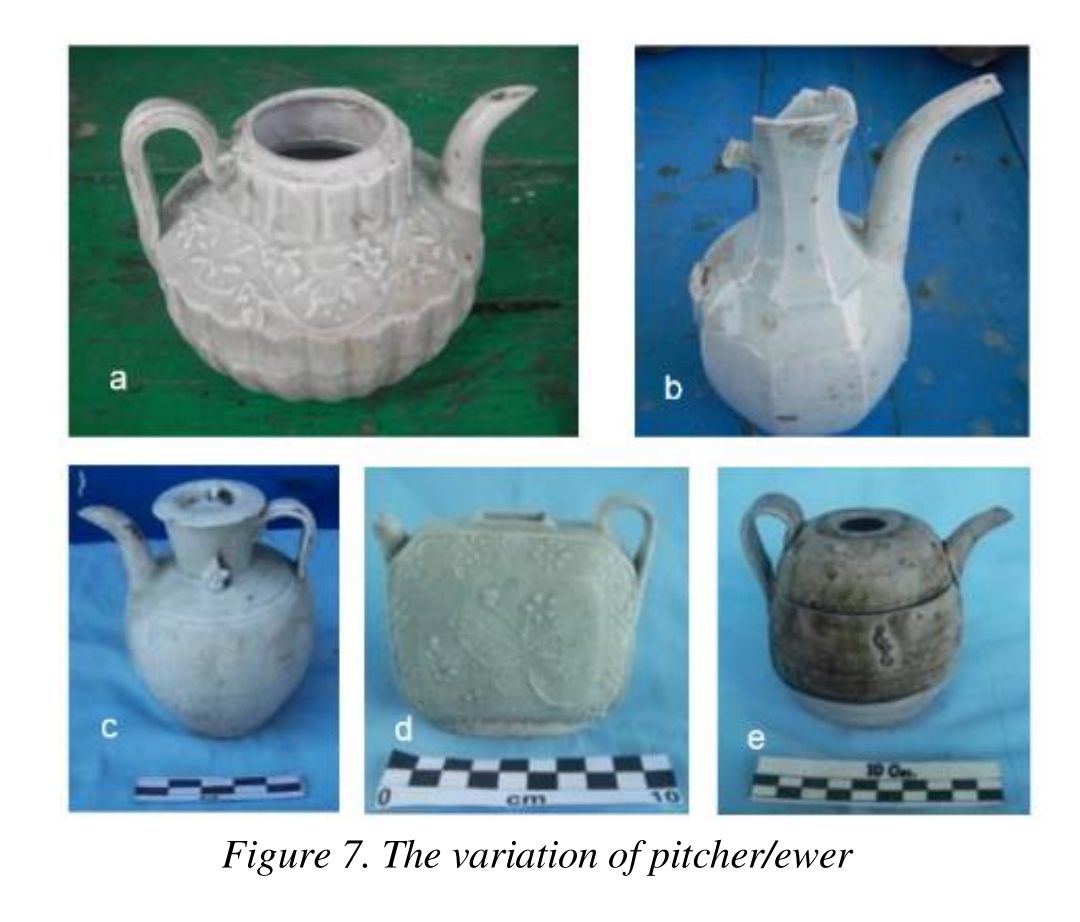

There were also a significant number of ewers, likely produced in Fujian Minqing kiln.

Examples of white wares from Wanpinglun (盖德碗坪崙) kiln Found in the Wreck

|

| Elaborately decorated floral‑shaped mouth vase from the Dehua kiln (Photo credit: Walter Kassela). |

|

|

| Dehua white glaze jarlet. |

Other Qingbai wares from Southern Fujian kilns found in the wreck

|

| The ewers are similar to those found in Sabah Flying Fish wreck, dated to the closing years of the Northern Song period. They could be products of Minqing kiln |

|

|

| Southern Fujian kiln qingbai bowl. Similar bowls have been found in Huaguang Jiao 1 and Java Sea wrecks. |

Brown Wares

The Jepara wreck also contained brown-glazed ceramics, including:

- Dark brown-glazed kendīs and jarlets.

- Celadon-glazed kendīs featuring iron-brown painted abstract motifs.

Most of these wares are attributed to the Cizao kiln in Quanzhou.

Examples of Brown glaze wares Found in the Wreck

|

|

| Fujian Cizao kiln brown glaze squat jarlet |

Dating the Jepara Wreck

- The presence of Jianyan copper coins (A.D. 1127–1130) confirms that the wreck dates to after A.D. 1130.

- The Fujian and Longquan green-glazed wares found suggest a timeframe of A.D. 1150–1200.

- The Dehua qingbai wares, likely from the Wanpinglun kiln, date to the late Northern Song or early Southern Song period.

- Fujian Qingbai octagonal ewer, Fujian green glaze bowls with carved/combed decoration, big Fujian green glaze bowl with Ji (吉) character, Cizao brown glaze squat jarlet in the wreck resemble items found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck (A.D. 1162). In Huaguang Jiao 1, a green glaze bowl with the incised cyclical date “ren wu (壬午载潘三郎造)” corresponds to A.D. 1162.

Given these factors, the Jepara wreck can be conservatively dated to A.D. 1150–1175. However, the presence of late Northern Song-style Dehua wares suggests it may represent a transitional phase between the Northern and Southern Song periods, possibly closer to A.D. 1150.

|

| The octagonal ewer (photo b) is similar to that found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck (Photo credit: Jujun Kurniawan). |

Concluding Remarks

The Jepara shipwreck stands as a significant archaeological find that enhances our understanding of maritime trade and ceramic production during a pivotal period in Chinese history. The diverse range of ceramics recovered—from Fujian and Longquan greenwares to Qingbai and brown-glazed items—reflects the sophistication and variety of production techniques employed during the Song and Yuan periods.

This wreck not only reinforces the critical role of Quanzhou as a major trading hub but also illuminates the intricate trade networks that connected China to numerous regions across Asia and beyond. The blend of decorative styles and production methods points to both continuity and innovation in ceramic artistry, underscoring the dynamic nature of cultural exchange during this era.

Despite the challenges posed by looting, the artifacts from the Jepara wreck continue to offer valuable insights. Future research that integrates ceramic analysis with maritime archaeology promises to further unravel the complexities of these trade networks and the technological advancements of the time. The Jepara wreck thus remains a vital link in understanding the transitional phases of ceramic production and the broader context of maritime commerce in medieval Asia.

Written by: NK Koh

(20 Mar 2010; updated 20 Mar 2013 and 25 Apr 2023, edited with ChatGPT on 7 Feb 2025.)

References:

- The Jepara Wreck – Atma Djuana & Edmund Edwards McKinnon

- Chronology of Longquan Wares of the Song and Yuan Periods – Kamei Meitoku

- 福建陶瓷考古概论 (An Introduction to Fujian Ceramics Archaeology) – 曾凡

- Jepara Shipwreck – Ceramics and Shipwrecks of Southeast Asia

- Some Note on The Salvaging Jepara Shipwreck - Jujun Kurniawan