Zhangzhou Wares in the Binh Thuan Shipwreck

The Binh Thuan shipwreck was first discovered in 2001 by fishermen attempting to free a trawl net caught in the wreckage. The shipwreck lies 41 meters (135 feet) below the surface, approximately 65 kilometers (40 miles) off the coast of Binh Thuan province, Vietnam.

During salvage operations in 2001, nearly 20,000 pieces of early 17th-century blue and white ceramics from Zhangzhou were recovered. Zhangzhou, located in Fujian Province, China, produced ceramics commonly known as Swatow wares, which were primarily exported to Southeast Asia and Japan. These wares are typically thick, heavily potted, and coarsely finished, lacking the refined craftsmanship of Jingdezhen porcelain. A distinguishing characteristic of Zhangzhou wares is the presence of sand adhesion on the outer base of plates.

The blue and white ceramics recovered from the Binh Thuan shipwreck are similar to those found in the Dutch East Indiaman ship Witte Leeuw, which sank near St. Helena in 1613 while returning to Europe.

|

|

| Typical grits on outer base | |

The Chinese junk carrying the Binh Thuan cargo was likely en route to the Malay Peninsula or Java when it sank off the southern coast of Vietnam in the early 17th century.

By the late 16th century, Zhangzhou had emerged as a major competitor to Jingdezhen in the ceramic trade. While Jingdezhen produced fine porcelain for elite markets, Zhangzhou catered to the lower-end markets of Southeast Asia and Japan.

Early Zhangzhou blue and white wares—such as those found in the San Isidro, and Nan’ao shipwrecks—were decorated in a vigorous, spontaneous calligraphic style. However, by the 1580s, Jingdezhen introduced Kraak porcelain, featuring motifs arranged in decorative panels. This European-preferred style gained popularity, prompting Zhangzhou kilns to adopt similar designs.

By the early 17th century, Zhangzhou’s calligraphic decorative style had nearly disappeared, with only a few examples found in shipwrecks like the San Diego (1600). The Binh Thuan wreck cargo mainly consists of Kraak-style Zhangzhou blue and white wares, decorated using the outline-and-wash method rather than the older calligraphic technique.

|

|

| Zhangzhou plate with calligraphc decorative style from Nanao wreck |

The Portuguese and Spaniards were the earliest European traders in China and Southeast Asia. However, by the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC), established in 1602, had replaced the Portuguese as the dominant force in the Southeast Asian and Japanese ceramics trade.

Research by maritime historian Petter Potters highlights trade collaborations between the Dutch and Chinese merchants. Archives in The Hague reveal that the VOC established trading bases in Banten, Johore, and Patani. In addition to exporting goods to Europe, they played an active role in regional trade within Asia.

VOC records detail trading contracts between Dutch merchants and Chinese traders, often involving barter and cash transactions. One example from the archives describes a trade agreement between Dutch merchant Victor Sprinckel and a Chinese trader named Teko in Patani. Sprinckel paid an advance of 148 mirrors, 250 glass panels, and 50 pieces of eight (silver coins) in exchange for a shipment of fine porcelain to be delivered the following year. Sprinckel assumed the risk of the outward and return voyage, while Teko’s friend provided financial surety.

Marine archaeologist Dr. Michel Flecker, who participated in the Binh Thuan wreck salvage, suggested that the wreck could be that of I Sinh Ho’s junk. A VOC report from Johore, dated 21 July 1608 and recorded by Abraham van den Broecke, mentions that I Sin Ho, a Chinese merchant, lost his junk at sea on its return voyage to Southeast Asia.

The majority of the Binh Thuan shipwreck cargo was auctioned by Christie’s in Australia in March 2004. The collection included:

The blue and white plates feature Kraak-style compositions, characterized by partitioned decorations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Zhangzhou blue and white wares from the Binh Thuan Wreck | |

|

|

Blue and white lion and overglaze red and green enamelled floral motif on inner and outer wall which is badly degraded |

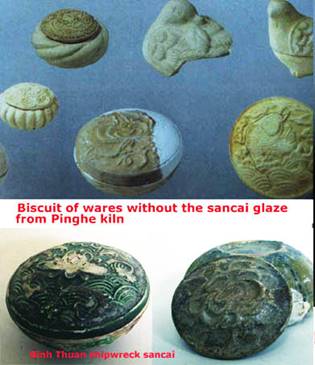

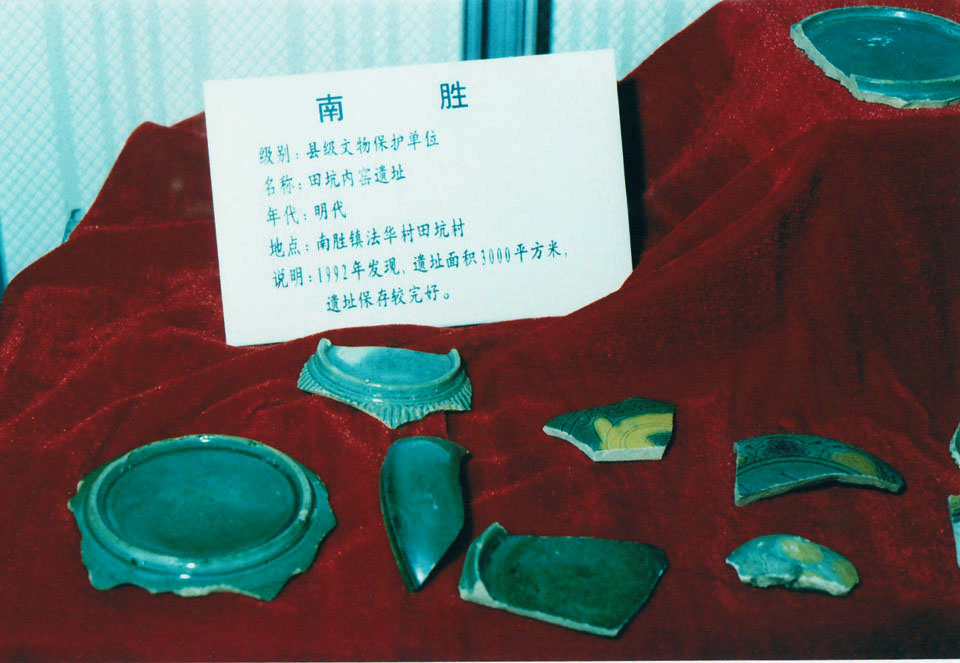

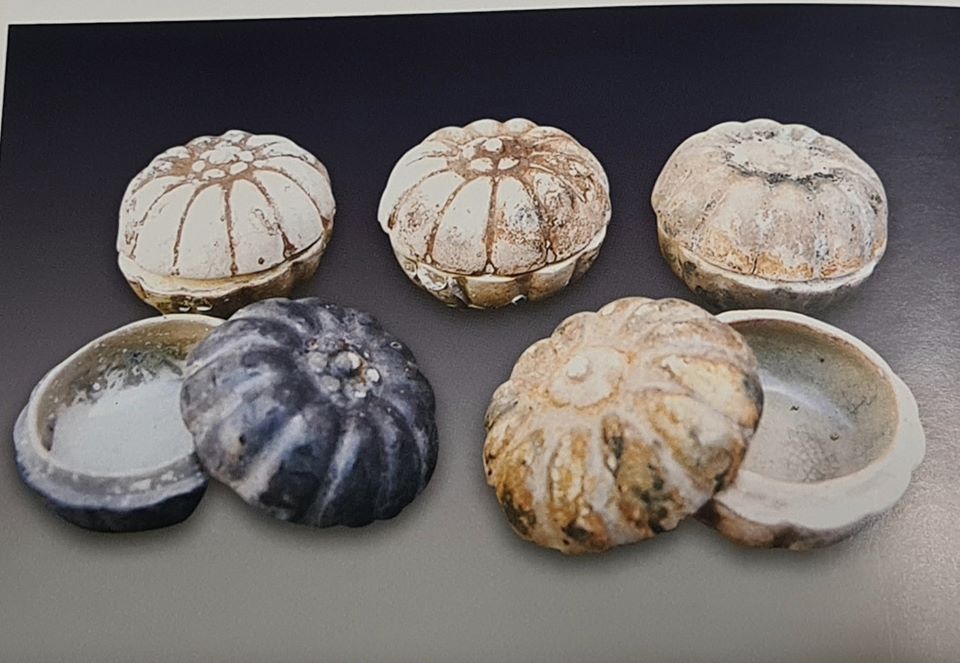

Christie’s suggested that the lead-glazed items came from Guangdong kilns, but this remains debated. Archaeological evidence indicates that similar biscuit forms (unglazed ceramics before glazing) were found in Zhangzhou kilns in large quantities. Fujian kilns—particularly in Cizao and Nanping—had been producing lead-glazed wares since at least the Song Dynasty, suggesting a continued production tradition into the Ming period.

|

|

|

|

| Lead glaze wares from Binh Thuan wreck |

The Binh Thuan shipwreck provides significant insight into the maritime trade networks of the early 17th century, illustrating the competition between Zhangzhou and Jingdezhen, the growing influence of the Dutch VOC, and the widespread demand for Chinese ceramics in Southeast Asia and beyond.

The recovered Zhangzhou wares mark an important transitional period in Chinese export ceramics, where the bold, spontaneous decorations of early Swatow wares gradually evolved into more structured Kraak-style compositions. This shift highlights the adaptability of Chinese potters in response to changing market preferences, particularly the growing European demand for Chinese porcelain.

Today, pieces from the Binh Thuan wreck serve as valuable historical artifacts, offering scholars, collectors, and ceramic enthusiasts a glimpse into the global ceramic trade of the 17th century. The shipwreck stands as a testament to the rich cultural and commercial exchanges that shaped maritime trade in Asia during this period.

Written by: NK Koh (20 Oct 2014), updated: 1 Mar 2025