|

|

|

Swatow ware is a unique type of Chinese ceramic known for its thick and coarse body, sandy bottom, and bold, freehand decoration. It has long been favored by collectors. The name "Swatow" originated from an early misunderstanding, as people once believed these ceramics were exported from Shantou (汕头) in Guangdong Province. However, during the Ming Dynasty, Shantou was merely a small fishing village and only developed into a formal port during the Xianfeng period of the Qing Dynasty.

|

|

|

| Late Ming Binh Thuan wreck plate showing the sand residual on the base |

Extensive archaeological investigations in the 1990s confirmed that the true production center of Swatow ware was Zhangzhou Prefecture in Fujian Province. The main production sites were in multiple counties, with Pinghe County at the core, along with smaller kiln sites in Hua'an, Nanjing, Zhangpu, Zhao'an, and Yunxiao. Additionally, neighboring areas in Guangdong, such as Dapu and Raoping, also produced similar ceramics.

|

| Map showing locations of Zhangzhou kiln sites |

During the Hongwu period of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang imposed a maritime ban (海禁) to curb the threat of Japanese pirates (wako) along the Zhejiang-Guangdong coastline. Official trade was only permitted through the tributary system, but many foreign merchants used it as a cover for actual trade.

Over time, the system weakened due to corruption and lax enforcement. By the Chenghua and Hongzhi periods (1464–1505), illegal overseas trade flourished, controlled by smuggling networks of landlords, merchants, and officials. A brief lifting of the ban during the Zhengde period (1505–1521) further stimulated trade, though the prohibition was reinstated during the Jiajing period with little success.

Fujian’s rugged terrain and limited arable land (only 20% of the province) made maritime trade essential for local survival. The ban led to widespread smuggling and even piracy. Yuegang, located in modern Longhai City’s Haicheng Town, gradually became a major trade port. From the mid-15th century onward, it played a crucial role in exporting Chinese porcelain, especially blue-and-white ware from Jingdezhen. The arrival of European merchants in the late 16th century further expanded trade. In 1567, the Ming government officially designated Yuegang as a legal foreign trade port to reduce corruption, increase revenue, and strengthen coastal defense against Japanese pirates. This decision cemented Yuegang’s position as an international trade hub during the late Ming period.

|

|

| Remnants of Yuegang Port in present day Haicheng town (海澄镇), Longhai City | |

Zhangzhou’s rich ceramic resources and proximity to Yuegang made it a significant porcelain production center. According to the Pinghe County Gazetteer (first compiled in 1545 during the Jiajing period), high-quality ceramics were already being produced in Nansheng and Guanliao. Archaeological evidence suggests some kiln sites date back to the Song Dynasty, but the industry peaked in the late Ming period, with only a few kilns continuing into the Qing Dynasty.

Marketing and pricing strategies for Zhangzhou ware followed the pattern of Fujian kilns from the Song and Yuan periods, targeting overseas low-end markets. Large quantities of Zhangzhou porcelain have been found in ancient sites, tombs, shipwrecks, and archaeological remains across Southeast Asia, Japan, Africa, and the Americas. For instance, Professor Jane Klose from the University of Cape Town noted that in South Africa, Jingdezhen porcelain is commonly found at colonial officials' sites, whereas Fujian ceramics are more frequently found among the general population.

Since the Song Dynasty, Chinese merchants had dominated ceramic trade in Southeast Asia. Ironically, the Hongwu maritime ban encouraged Fujianese migration to the region, further expanding their trade networks. Archaeologists in Malaysia have discovered "South China Sea-type" ships, built from tropical hardwood using both wooden and iron nails, which provide evidence of this period’s maritime trade. Notable shipwrecks include the Nanyang (1380), Longquan (1400), Royal Nanhai (1460), and Xing Tai (1550).

By the early 16th century, China’s dominance in Southeast Asian trade weakened, and European colonial powers entered the market. The Portuguese first arrived in China in 1513 and moved to Yuegang in 1522, establishing trade ties with local merchants. The Spanish reached the Philippines in 1521 and made Manila a trade hub, developing the famous Manila Galleon Trade, which transported goods from China, India, and Southeast Asia to the Americas.

The Dutch entered the Southeast Asian market in 1602, occupying Taiwan in 1624 and using it as a trading base. In the early 17th century, they frequently attacked Portuguese, Spanish, and Chinese ships, severely disrupting Yuegang’s trade. Eventually, the Dutch gained dominance in Southeast Asian maritime trade.

After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, Zhangzhou's ceramic industry began to decline. When Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) expelled the Dutch from Taiwan, coastal Fujian and Guangdong became frontline regions in the Qing government's efforts to suppress Ming loyalist forces. In 1662, Emperor Kangxi issued the Coastal Evacuation Order (迁界令), forcing coastal residents inland to cut off supplies to Taiwan. This policy severely impacted the coastal economy. Although the maritime ban was lifted in 1682, Yuegang’s trade role had already been overtaken by Xiamen, leading to the decline of Zhangzhou kilns. Ultimately, production was replaced by kilns in Dehua and surrounding areas.

A major archaeological survey published in 1997 confirmed that Zhangzhou's ceramic production was centered in Pinghe County (漳州平和县), with key kiln sites at Da Long (大垅) and Er Long (二垅) in Wuzhai (五寨), as well as Nansheng Huazai Lou (南胜花仔楼).

Excavations have revealed that Swatow wares were fired in saggars. To prevent glazed vessels from adhering to the saggar during firing, potters spread a layer of sand (up to 2 cm thick) on the base. This method helped minimize warping, especially for large plates, but often left residual sand patches on the final product. Smaller vessels, such as bowls, were typically fired in stacks, as evidenced by the unglazed stacking rings found on their inner bases.

The highly disturbed nature of the kiln sites has made stratigraphic dating challenging, complicating efforts to establish a precise production chronology. While blue and white wares from Nansheng Huazai Lou and Wuzhai Er Long exhibit distinct characteristics, it remains unclear whether these differences represent sequential production phases or regional specialization.

Mrs. Sumarah Adhyatman, in her book Zhangzhou (Swatow) Ceramics, classified Zhangzhou blue and white wares based on decoration styles:

Archaeological surveys support this classification. The calligraphic style was most prevalent at the Wuzhai Er Long kiln, whereas the outline and wash technique was predominantly produced at Nansheng Huazai Lou kiln. While Er Long also produced some later-style wares, they were in significantly smaller quantities. A more detailed study of Er Long products may help identify transitional examples.

Excavated example from Wuzai Erlong Kiln (五寨二壠窑)

Outline and Wash type from Nansheng Huazai Lou kiln

Since the 1990s, shipwreck cargoes have provided valuable insight into the chronology of Zhangzhou ceramics, serving as time capsules for export wares. These wrecks suggest two major production phases:

While a small number of calligraphic-style pieces continued to be produced into Phase II, the outline and wash style became predominant. The Hatcher and Wanli cargoes contained only a few Zhangzhou wares, and the limited variety found at Vung Tau suggests a decline in Zhangzhou kiln production by the late 17th century.

|

|

| Binh Thuan Shipwreck plates with human motifs (a typical example of Wanli and later periods using the outline and wash method) | |

|

|

Wanli kraak-style blue and white charger from a Pinghe kiln |

|

|

|

Binh Thuan Shipwreck bowl with ducks in lotus pond

The San Isidro wreck is believed to represent the earliest phase of Zhangzhou export production. Among the artifacts recovered were Thai Sawankhalok jarlets with iron-black painted decoration, which helped establish a terminus post quem.

Additional shipwrecks, such as Xuande and Singtai (off the east coast of West Malaysia), contained similar Thai wares, supporting a dating of around 1540. In 2019, thermoluminescence (TL) testing by the Shanghai Museum on two Jingdezhen blue and white samples from the Nan Ao 1 wreck produced dates corresponding to 1569–1571 A.D. (2nd to 5th years of the Longqing reign, 1567–1572 A.D.). Other Jingdezhen ceramics found in the Blanakan and Nan Ao wrecks exhibit clear late Jiajing to Longqing characteristics.

Calligraphic-style Zhangzhou pieces have also been found in an unidentified shipwreck near Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. Initially thought to be the San Felipe galleon (sank 1576 A.D.), more recent research suggests it may instead be the San Juanillo (sank 1578 A.D.).

|

|

Thai Sawankhalok jarlet from San Isidro Wreck |

.

Examples of calligraphic decoration from the San Isidro wreck

Calligraphic floral decoration from the Blanakan wreck

|

|

|

| Zhangzhou blue and white from the Nan Ao shipwreck (calligraphic style) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Examples from unknown wrecks near Indonesia | |

|

|

|

| Examples from the San Juanillo wreck |

Examples of Early Zhangzhou Wares from Philippines and other Private Collections

Collections from the Philippines reveal many outstanding blue and white wares from the early production phase. These elaborately decorated pieces, which represent the highest quality achieved by the potters, are comparable to examples recovered from the Wuzhai Er Long kiln. Notably, plates from the Er Long kiln tend to have an even layer of glaze on their external bases, whereas pieces from the later-phase Nansheng Huazai Lou kiln often display patchy or missing glaze in these areas.

|

|

| Two beautiful examples from the Philippines Bautista collection | |

|

|

| A comparable piece from the Er Long kiln excavation | |

Plate with "ladies in garden" from the Ching Ban Lee Gallery

Example with human motif from Er Long Kiln

Example with elaborate floral decoration from Er Long Kiln

|

|

|

| Plate with a chiling motif showing an even glazed outer base | |

|

|

|

| Example with lotus decoration from a Private collection | |

During the later phase, two significant developments occurred. First, the outline and wash painting technique—based on the “kraak” style introduced by Jingdezhen potters—became dominant. Second, a wider range of products emerged, including:

|

|

| From the San Diego wreck. Left Jingdezhen kraak plate and right Zhangzhou kraak inspired type | |

|

|

|

The typical more

sparse compostion of Er Long later phase blue and white |

|

|

|

|

Typically more crowded

decoration and complex partitioning adopted by the Nansheng Hua

Zailou potters |

|

|

|

| This example from my collection could be from the Er Long kiln. It has the more sparse composition and the characteristic relatively even glaze on outer base | |

|

|

|

|

Zhangzhou blue and white (the persistent type) using the outline and wash method

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Two Examples of big plates with kraak style decoration | |

Jingdezhen Overglaze enamelled examples from Nanao wreck

Fragments from Nansheng Hua Zailoug kiln

Fragments from the Nansheng Hua Zailou kiln

|

|

|

| Overglaze enamelled big plate with landscape motif | |

3 overglaze enamelled big plates from a Private collection

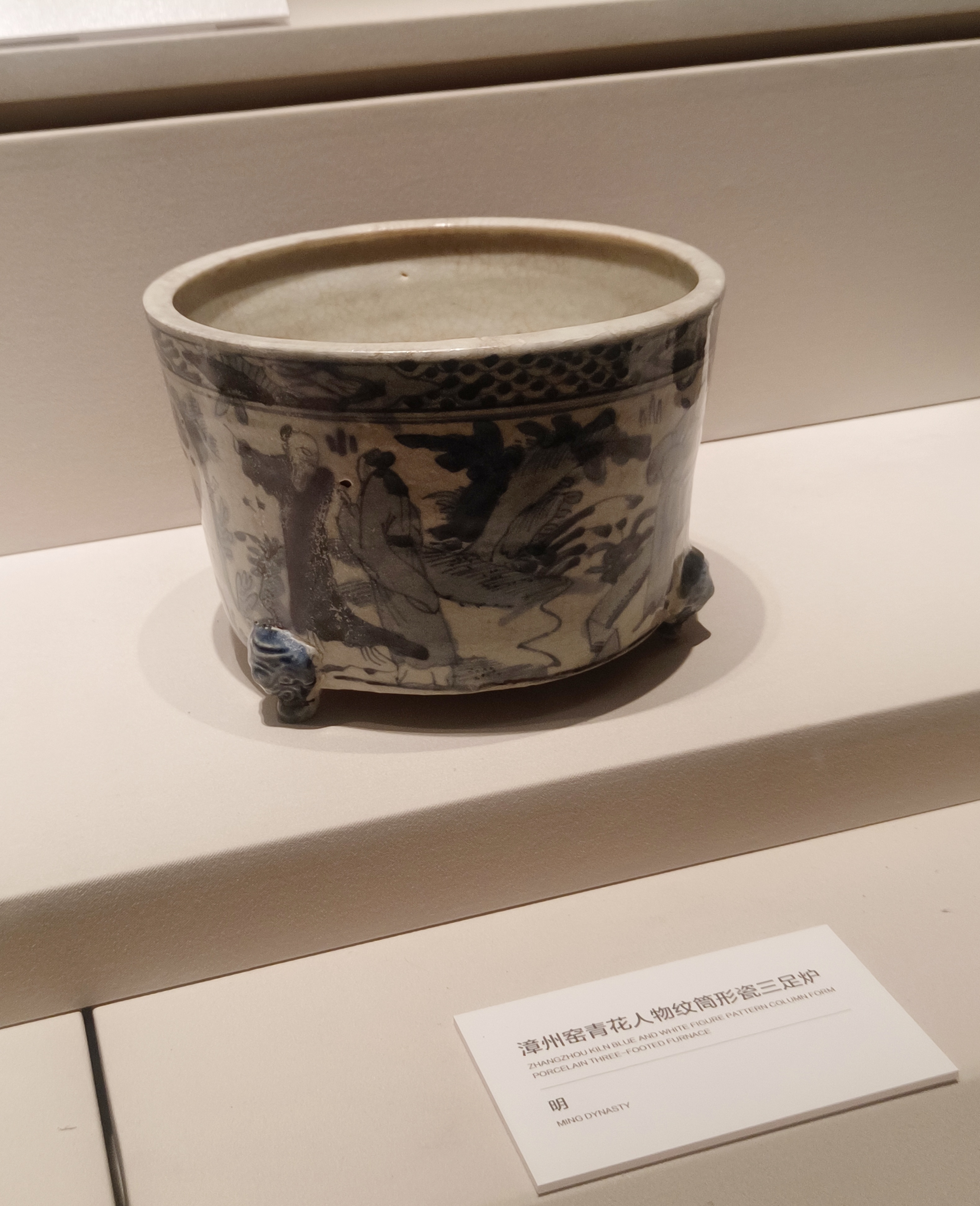

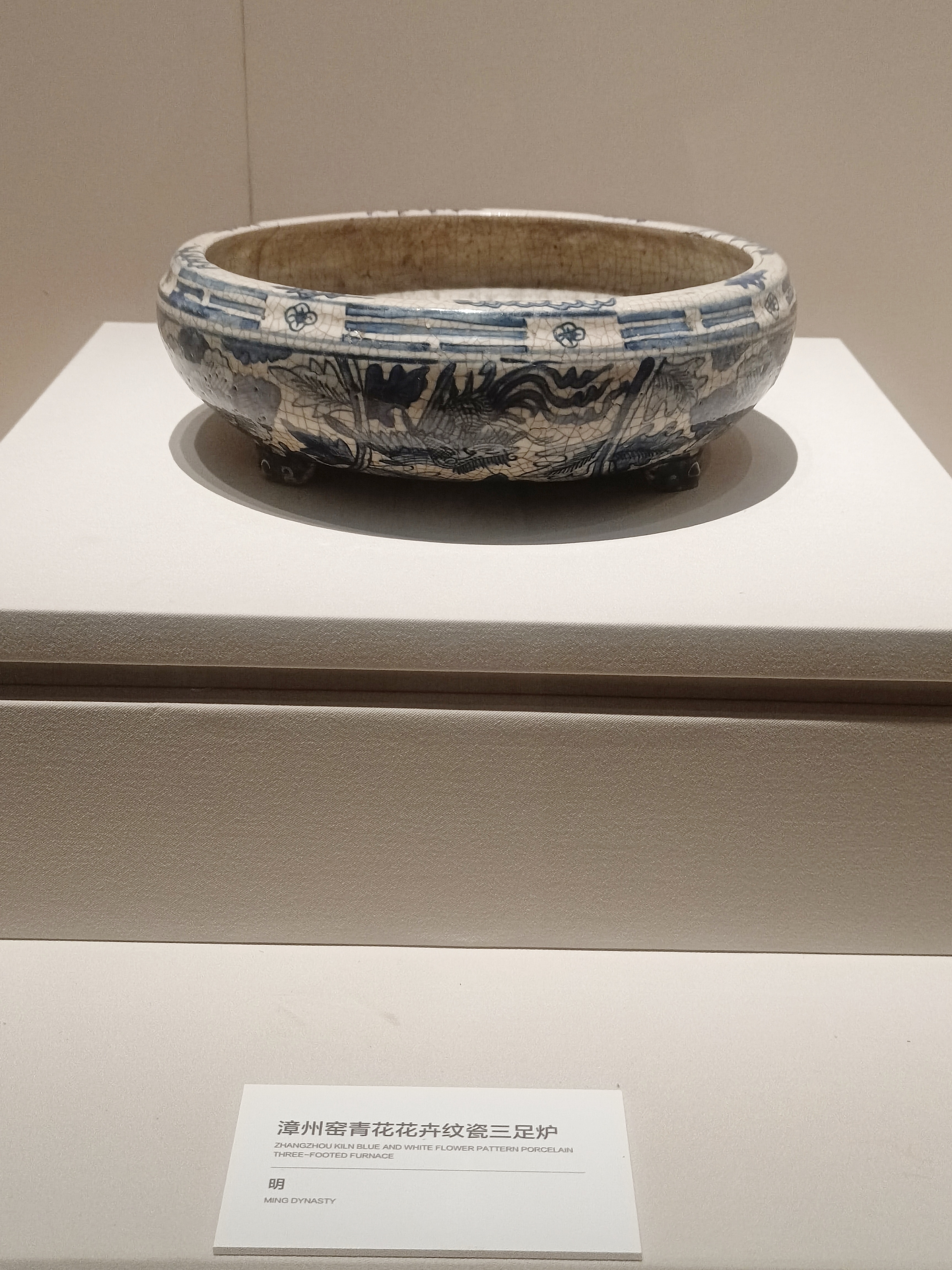

2 examples from Xiamen Museum

Two examples in Zhangzhou Museum

Example with degraded enamels from the Binh Thuan wreck

|

|

| Jingdezhen Wanli examples of white slip decoration | |

|

|

|

|

| Two brown-glazed plates with slip-painted decoration from the Chongzhen Hatcher cargo | |

|

|

|

| Brown-glazed kendi with abstract white slip floral decoration from Sumatra |

|

White-glazed plate with inner base decoration |

|

|

|

| Celadon-glazed big plate with an incised fish-leaping motif | |

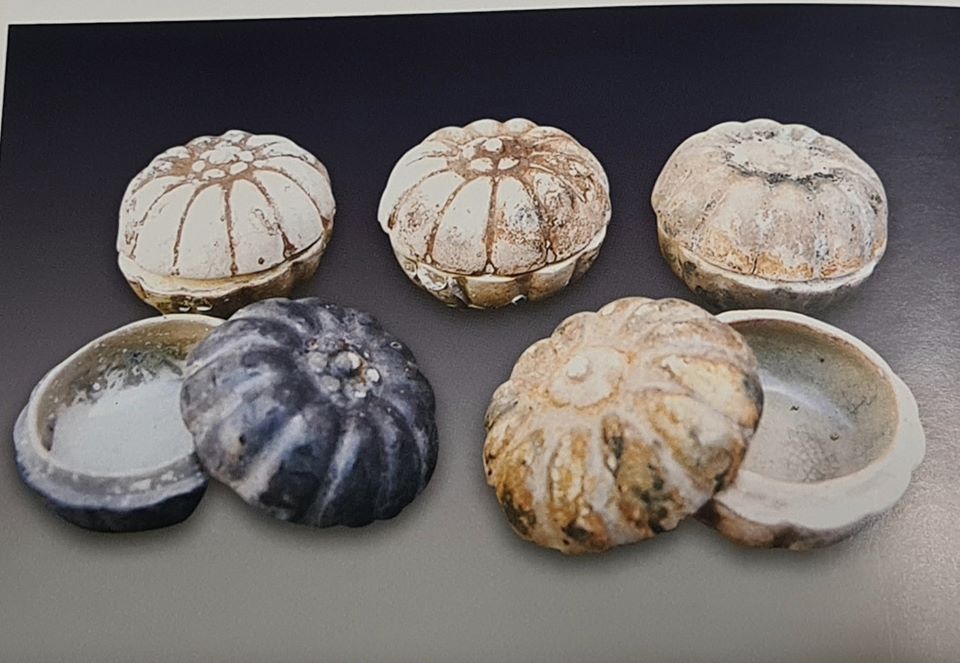

Two Sisancai cover boxes from Japanese collection

Lead glaze lidded boxes from Binh Thuan wreck

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Susancai cover boxes found in Sumatra |

|

Ming Chongzhen Zhangzhou lead glaze cover boxes from the Hatcher wreck |

Susancai pieces with incised floral motifs

|

|

| Susancai jarlet with incised abstract decoration |

The kilns in Pinghe County produced a comprehensive range of wares, including large chargers that are rarely found elsewhere. Ceramics from Zhaoan kilns, for example, tend to be of higher quality, more thoroughly fired, and usually feature glazed outer bases. Distinguishing pieces produced during the Jiajing Period remains challenging, as very similar types were produced throughout the late Ming period.

For further details and views of shards from various kiln sites, please refer to:

|

|

| Late Ming bowl with landscape and poetic inscription. | Late Ming bowl with chi dragon motif |

|

|

| Late Ming bowl with kraak style floral motif. | Late Ming bowl with kraak style motif on interior. |

|

|

| Vung Tau cargo dish with landscape. | Late Ming bowl with Dragon motif. |

|

|

|

Late Ming

Vase with galloping horses

|

Late Ming

kendi with floral motif

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Examples exhibited in Zhangzhou Musuem |

The study of Zhangzhou (Swatow) wares provides valuable insight into the economic, technological, and cultural exchanges that shaped the late Ming maritime world. These ceramics, known for their spontaneous decorative styles and distinctive sandy bases, were produced primarily in Zhangzhou Prefecture and exported in vast quantities to Southeast Asia, Japan, the Middle East, and even Africa and the Americas.

The rise of Zhangzhou kilns was closely linked to the fluctuating maritime policies of the Ming Dynasty, particularly the lifting of the trade ban in 1567 and the legalization of Yuegang as a port. The interplay of local economic pressures, foreign demand, and European mercantile ambitions fueled the growth of this ceramic industry. Shipwreck discoveries, such as those of the San Isidro, Nanao 1, Binh Thuan, San Diego, and Vung Tau cargoes, have been instrumental in piecing together the chronology and stylistic evolution of these wares.

Over time, Zhangzhou potters diversified their production, incorporating techniques such as overglaze enameling and white slip decoration, likely influenced by Jingdezhen innovations. However, the decline of Zhangzhou kilns was inevitable after the fall of the Ming, exacerbated by Qing-imposed coastal evacuations and the shifting dominance of ports like Xiamen. While Zhangzhou wares faded from prominence, their historical significance endures, shedding light on the broader dynamics of Ming global trade and ceramic artistry.

The legacy of Swatow wares continues to captivate scholars, collectors, and archaeologists. As new discoveries emerge, they will further refine our understanding of these fascinating ceramics and their role in the interconnected world of the late Ming period.

Written by: Koh Nai King

Original

Publication Dates: October 07; updated November 29,

2010 and June 08,

2024. Edited with ChatGPT on 7 Feb 2025.