During the Northern Song Dynasty, China faced persistent threats from nomadic tribes in the north and northwest, disrupting overland trade along the Silk Road. Since foreign trade was a crucial revenue source, the government prioritized expanding maritime commerce. Mingzhou became the primary trade hub for Korea and Japan, while Guangzhou facilitated commerce with Southeast Asia, India, and the Middle East.

In 971 A.D., the Song government established the Office of Maritime Trading in Guangzhou to regulate imports, exports, and taxation. Guangzhou remained the dominant port until the late Northern Song period when the rise of the Jin Dynasty forced the imperial family to relocate to Hangzhou. Following this shift, Quanzhou emerged as the main trade port for the Nanhai region and beyond.

Initially, Arab, Indian, and Southeast Asian ships dominated trade with China. However, by the Song Dynasty, Chinese advancements in shipbuilding and navigation enabled their own junks to travel long distances, strengthening China’s maritime presence and expanding trade networks.

Meanwhile, Srivijaya’s maritime dominance weakened due to naval raids by the powerful Chola Kingdom of Southern India, disrupting its control over trade routes. This decline shifted the political center to the Melayu Kingdom in Jambi, which emerged as a key regional power. Archaeological evidence indicates that this transition coincided with a significant influx of Guangdong ceramics into the region.

Large quantities of Guangdong ceramics have been discovered in the Batang Hari River, particularly at Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra’s Jambi region, highlighting Guangdong’s expanding role in trade during the late Northern Song period.

The Cirebon and Intan

Findings from the Cirebon wreck included a large quantity of Yue wares featuring finely incised dragons, phoenixes, parrots, human figures, and floral motifs. Similar wares have been recovered from the Musi River in Palembang, reinforcing their role in regional commerce.

Recent shipwrecks in Indonesia’s Lingga Archipelago indicate significant shifts in trade ceramics by the second half of the 11th century.

Since 2012, significant numbers of Guangdong ceramics have been recovered from Batang Kumpeh, a tributary of the Batang Hari River in Sumatra’s Jambi region.

Several factors mark the mid-11th century as the beginning of Guangdong’s golden period in trade ceramics:

By the mid-11th century, Yue-inspired carved and painted decorations, along with Qingbai wares, were in full production. This period marks the rise of Guangdong as a dominant force in trade ceramics.

|

|

|

|

|

Bowls with 4 characters Zhihe Yuan Nian

(至和元年) i.e. 1054 A.D |

|

By the late Northern Song period, Guangdong kilns had revolutionized the trade ceramics industry by capitalizing on key market shifts and strategic adaptations.

Several factors contributed to the decline of Yue kilns, creating an opportunity for Guangdong kilns to rise:

Guangdong kilns responded to these challenges with an innovative and diversified approach:

This business model ushered in a golden era for Guangdong ceramics, establishing the region as the leading producer of late Northern Song trade ceramics.

Archaeological excavations have provided insights into the contributions of key Guangdong kilns:

Together, these kilns supplied virtually all major types of Guangdong export wares found overseas, cementing the region’s dominance in trade ceramics.

This business model led to a golden era for Guangdong ceramics, securing its status as the leading producer of late Northern Song trade ceramics.

Xicun is located about 5 km northwest of Guangzhou, in an area called Huangdi Gang (皇帝岗), meaning "Emperor's Hill." A preliminary excavation report was published in 1958. Despite being a last-minute salvage excavation in 1956—conducted before the site was demolished to make way for a stadium—the range of products discovered was remarkably diverse. Interestingly, based on Guangdong ceramics recovered from shipwreck cargoes and excavated from ancient burial and habitation sites in Southeast Asia, a majority of the types can be traced to Xicun or related origins.

| A Selection of Ceramics recovered from Xicun kiln in Guangdong Shi Museum |

The 1958 Xicun excavation identified 15 types of ceramic vessels, including:

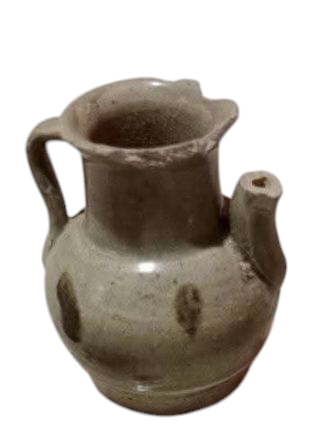

Traditional Guangdong green-glazed vessels are typically made of coarse paste and exhibit a runny, patchy, snake-skin-like glaze. Many utilitarian wares, especially jars of various sizes, were produced in kilns located in the Pearl River Delta and exported as early as the Tang Dynasty.

During the Tang period, the glaze was generally a lighter green in tone. By the Northern Song period, it had developed a more brownish-green hue, with most pieces fired at lower temperatures. As a result, the glaze had poorer vitrification and tended to flake easily. Many examples recovered from shipwrecks show severe degradation, with their bodies almost entirely stripped of glaze.

The most common vessel forms included jars, ewers, and basins. A significant number were decorated with impressed floral patterns arranged in various compositions. Some rarer designs, such as dragons and phoenixes, also exist. Notably, I have seen a piece in a Philippine collection featuring an impressed twin-phoenix motif, stylistically similar to the incised versions found on Yue ware.

Findings from known shipwrecks indicate that traditional Guangdong green-glazed ware remained a staple in maritime trade until the end of the Northern Song period. For instance, the Lingga wreck contained many brownish-green, basin-shaped vessels with impressed floral motifs, which are products of the Xicun kiln. Similarly, the Pulau Buaya wreck also carried a quantity of these wares.

|

|

| Green glaze basins : 3 with impressed floral and 1 with dragon decoration from the Lingga wreck | |

|

|

|

|

| A Basin with impressed fish motif. Recovered from Batang Hari River in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A Basin featuring an impressed dragon motif. On display in the Ching Ban Lee Gallery, Manila. | |

|

|

|

| Three ewers from the Lingga wreck. Remnant traces of glaze can still be seen on the ewers, displaying typical Guangdong glaze characteristics. The two ewers on the right were found in large quantities in several wrecks, as well as in many habitation and burial sites across Southeast Asia. The ewer on the left is in the kendi form, which was particularly popular in Southeast Asia. Similar forms with unglazed, creamy paste are believed to have been produced in Satingphra, Southern Thailand. | |

|

|

|

|

| Brownish green glaze ewer and kendi. From the Bautista Collection, Manila. | |

|

|

| A brownish green glaze ewer. From the Ching Ban Lee Gallery, Manila. | |

|

|

| Two brownish green glaze ewers. Recovered from the Batang Hari River in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| This jar, featuring lugs on its shoulder, is classic Guangdong utilitarian ware which has been produced since the Tang period. Its form has remained largely unchanged and continued to in demand during the Northern Song period. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A Lingga wreck bulbous jar with missing gkaze. An example with a well-preserved glaze is provided for comparison. Similar jars were also discoered in the Pulau Buaya wreck (1989). | |

2. Yue-inspired green-glazed wares (carved/combed and iron-brown motifs)

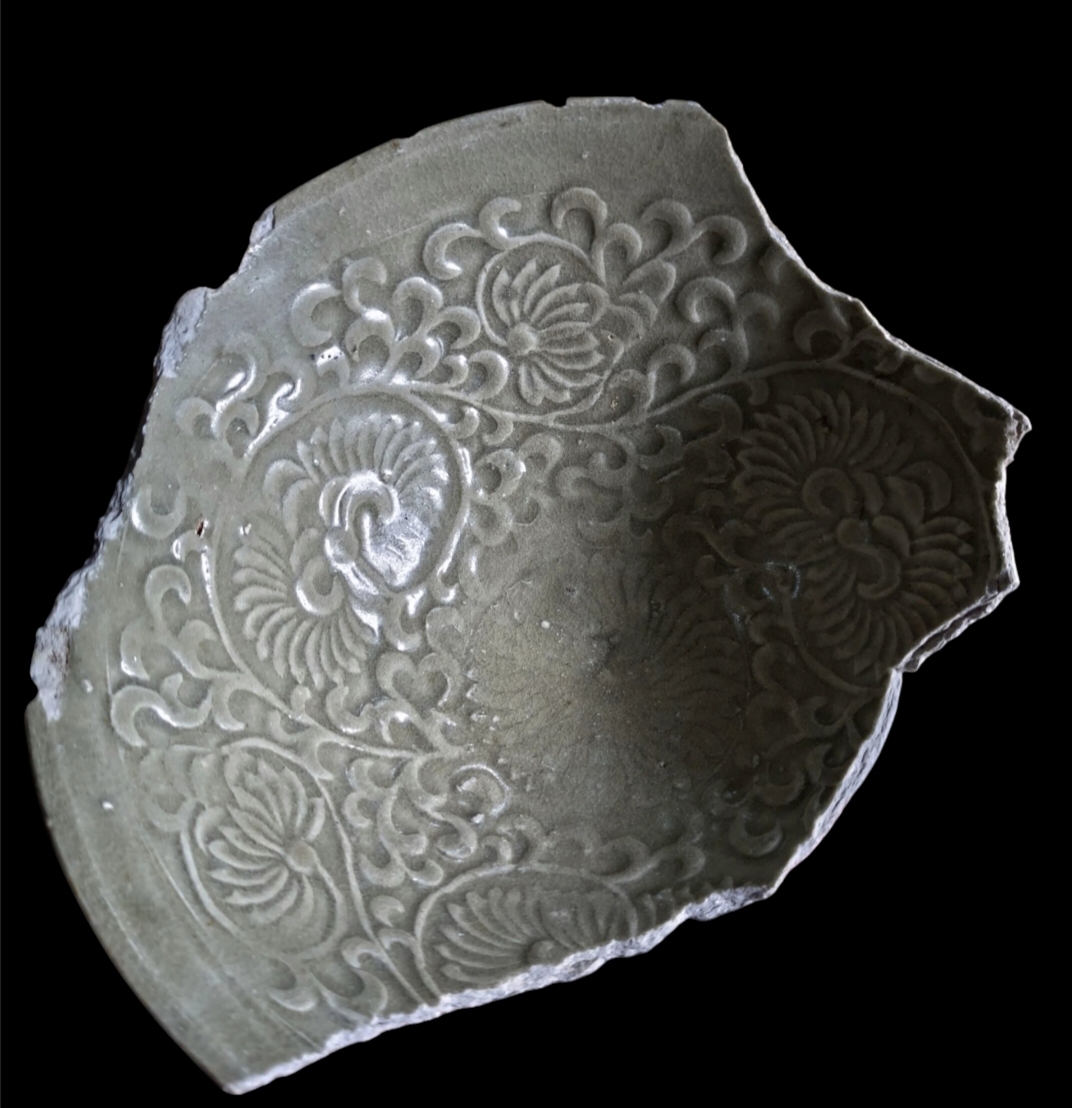

Xicun adopted the Yue glazing formula, and stylistically, its carved and combed decorations reflect strong influences from the Mid-Northern Song Yue decorative tradition, with additional elements inspired by Yaozhou ceramics.

However, Xicun’s connection to Yue-style iron-brown painted decoration remains less evident. Recent archaeological discoveries in China have revealed that Wenzhou produced a significant quantity of iron-brown decorated wares.

Wenzhou’s production of iron-brown painted ceramics began no later than the Early Northern Song period, likely influenced by Changsha—a center renowned for its pioneering use of iron-brown and copper-green painted designs. Interestingly, I came across a late Tang Changsha ewer from the Vietnam Chautan wreck and a Wenzhou ewer from a Northern Song grave, both of which share striking similarities in vessel form and decoration.

The products from Wenzhou are considered Yue-type, as they exhibit strong similarities in glaze appearance and decoration. It is not far-fetched to suggest that Xicun, in turn, drew inspiration for its iron-brown decoration from Wenzhou. In fact, Wenzhou’s influence on Xicun may be greater than previously assumed, as both share a strikingly similar lighter greyish-green glaze tone.

|

|

| Wenzhou kiln ewer from a Northern Song grave and a late Tang Changsha ewer with painted decoration. | |

|

|

|

|

A group of large Xicun bowls with a greyish-green glaze, adorned with bold iron-brown painted floral motifs. The bowls measure 33 cm and 23 cm in diameter, respectively. They surfaced on the Singapore antique market around 2012, having been salvaged from the Lingga wreck. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Most of the bowls feature a tapered foot; however, a small number have a crude, square-cut foot and are more high-fired. This suggests they may come from different kilns near Xicun. For example, archaeological surveys have revealed that iron-painted bowls were also produced in kilns such as Nanhai Wentou Ling (南海文头领) and Shabian (沙边). | |

|

|

| Shards from Shabian kiln | |

|

|

| Examples with iron-brown painted floral motif painted on a pillow and a bowl fragment. Exhibited in Guangdong shi museum (广东市博物馆). | |

|

A bowl with iron-brown painted stylised flowers encircled by carved floral motif on the inner wall. |

|

|

|

|

|

| A fine example from the Philippines, this piece showcases a carved and combed floral design surrounding a parrot, with meticulously placed iron-brown spots. | |

|

|

|

| This example features carved and combed floral decoration, accented with carefully placed rosettes of iron-brown spots. Stamped arcs define the floral petals, a hallmark of Xicun ceramics. From an Indonesian collection. | |

|

|

| An unusual iron-brown painted floral design, encircled by radiating carved slanting lines. Found in the Batang Hari River in Jambi, in Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A greyish-green glazed pillow with carved/combed floral decoration. Recovered from the Xicun kiln site. | |

|

|

| A light greyish-green bowl features carved and combed decoration on the interior. The exterior is adorned with radiating carved striations—a decorative motif popular in contemporaneous Yaozhou and Qingbai wares. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A light grayish-green bowl from an Indonesian shipwreck,

featuring carved and combed floral decoration. The petals are

outlined with stamped arcs, a distinctive decorative element of the

Xicun kilns. A similar example is in the collection of the Guangdong

Provincial Museum.

A fine example featuring carved and combed floral design,

with the floral petals defined by stamped arcs. From the Ching

Ban Lee Gallery, Manila.

|

|

|

|

|

| A rare light grayish-green glazed cover fragment, adorned with a carved and combed blooming flower. The ground is stamped with dots. The design is likely inspired by decorations on metalwork. From a wreck near Quy Nhon in Vietnam. | |

|

| The ewer features a phoenix-head, with its body adorned with carved floral motifs on the belly and a band of outlined lotus petals along the lower wall. The floral petals are defined by stamped arcs, a distinctive element of Xicun ceramics. It was discovered in Central Vietnam. |

|

| A phoenix-head ewer with a ribbed neck and lobed body. The glaze exhibits a distinct bluish cast in area where it has pooled. This piece was discovered in Central Vietnam. |

|

|

| A green glaze phoenix-head ewer with body adorned with carved and combed floral decoration. From the Ching Ban Lee gallery, Manila. | |

|

|

| A phoenix-head ewer with carved and combed floral decoration, further embellished with iron-brown spots arranged in a rosette form. From the Bautista Collection, Manila. | |

|

|

| A group of light greyish-green glazed phoenix-head ewers. From the River Batang Kumpeh, a tributary of Batang Hari in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A greyish-green glazed ewer with iron-brown spots From the River Batang Hari in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A beaker-shaped cup, featuring carved and combed floral decoration, further embellished with randomly placed iron-brown spots. From the River Batang Hari in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A beaker-shaped cup adorned with carved lotus petals and randomly placed iron-brown spots. | |

|

|

| A small, bulbous, light greyish-green jar with four lugs. It is adorned with carved and combed floral motifs, further embellished with rosette-shaped iron-brown spots. From the River Batang Hari, Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

| A lobed body jar and a lidded small jar. Both from a wreck near Singkep Island, Lingga Archipelago. | |

|

|

| Two examples of greyish-green glazed small jars decorated with lotus petals. One on left from a wreck near Belitung and the other Singkep Island. | |

|

|

| A small greyish-green glazed jar with iron-brown spotted decoration. From the River Batang Hari in Jambi, Sumatra. | |

|

|

|

|

Three small ribbed-neck vases are displayed on the left. Two

feature a greyish-green glaze adorned with iron-brown spots, while

the third exhibits a striking bluish Jun-like glaze. These were

recovered from a shipwreck near Singkep Island, Sumatra.

The remaining two vases, sourced from the Lingga wreck,

display an elongated form and a bluish-green hue. Their style

suggests they may originate from kilns in Guangdong, though further

analysis is needed to confirm their precise provenance.

A small, elongated jar coated in a greyish-green glaze, adorned with two opposing bands of lotus petals carved in high relief. |

|

|

|

| A greyish-green glazed bowl adorned with high-relief lotus petals.. | |

|

|

| A greyish-green glazed dish-mouthed vase. From a wreck near Singkep Island, Lingga Archipelago. | |

|

|

| A Xicun greyish-green glazed floral-shaped dish. | |

|

|

| One the left is a Xicun box with bird-shaped lid which is on display in the Guangdong Shi Museum. The other of similar form, is from an Indonesian collection. | |

|

|

| Two degraded glazed boxes with a bird-shaped lid. From a wreck near Singkep Island, Lingga Archipelago. | |

|

|

|

|

| A beautiful two interconnected circular boxes with a bird-shaped lid. | |

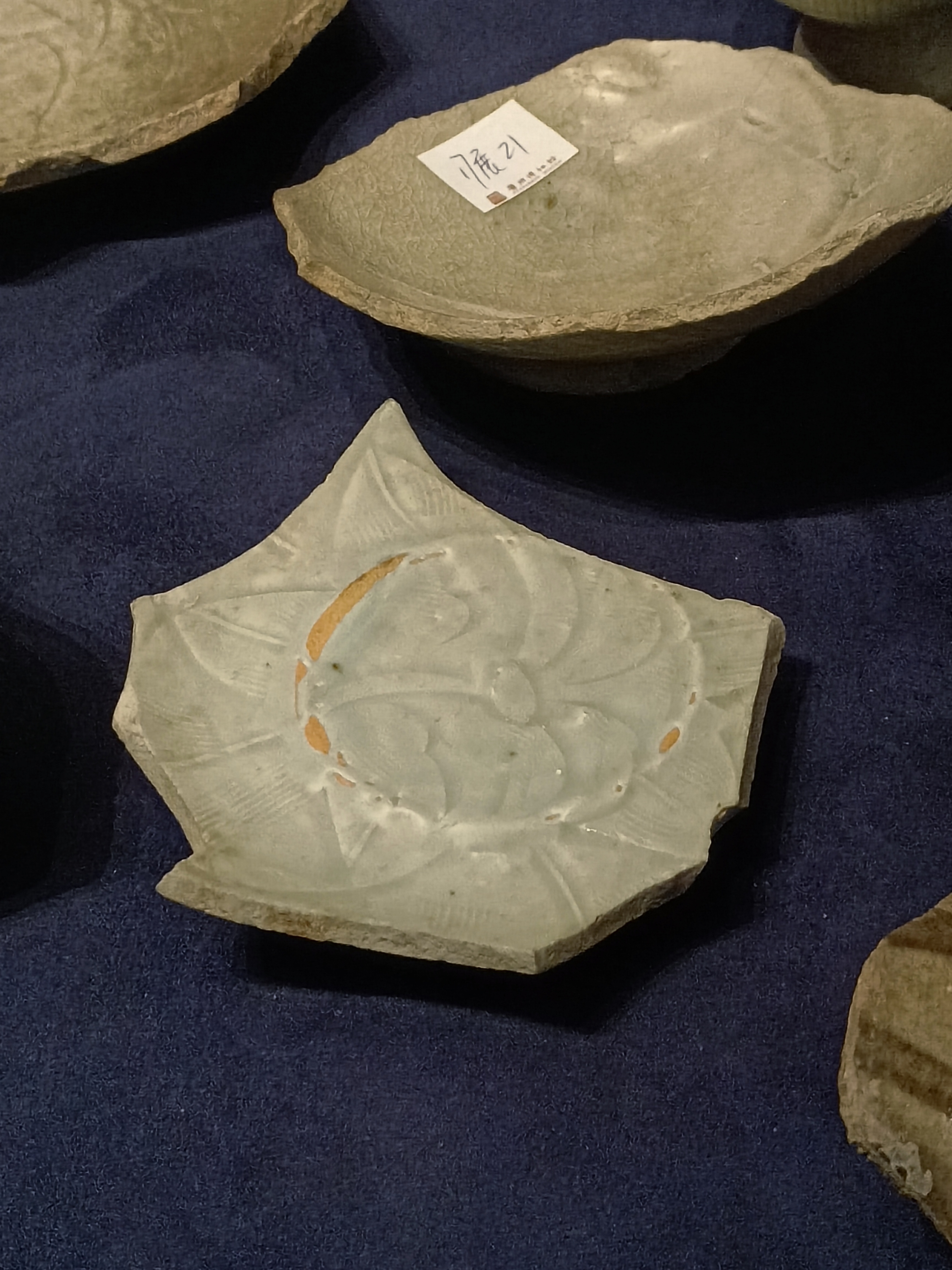

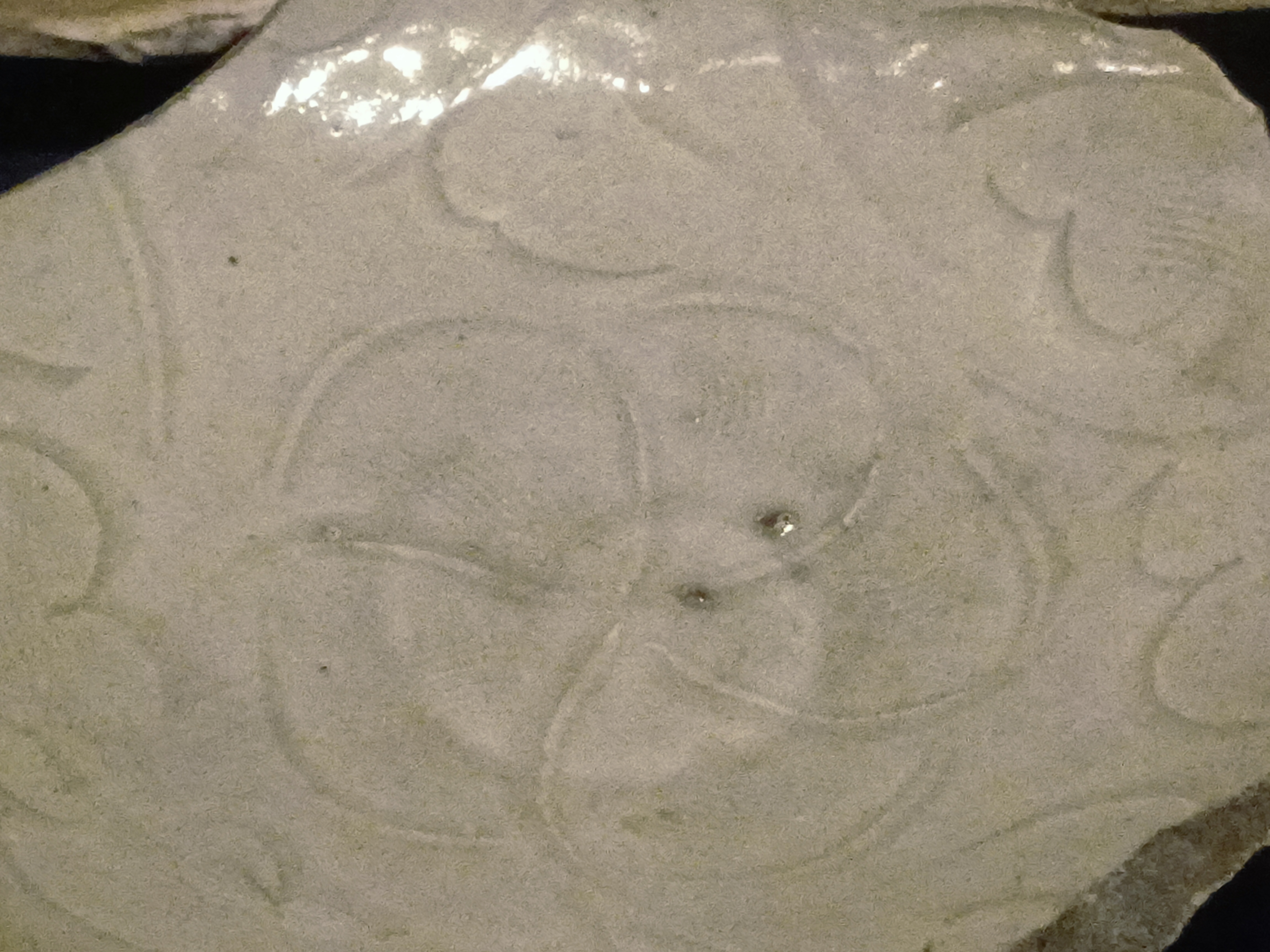

Our understanding of Qingbai wares produced by the Xicun kiln relies primarily on two key sources: a brief 1958 report from a Chinese archaeological survey and a more comprehensive 1987 study by The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Despite their importance, Xicun Qingbai wares are rarely highlighted in publications on Chinese ceramic collections. Further complicating matters, the photographs in these reports are mostly in black and white, obscuring critical details such as glaze color and making it difficult to visualize the vessels accurately.

During a visit to the Guangzhou City Museum on November 27, 2024, I photographed Qingbai shards from Xicun kiln site on display. This firsthand examination provided valuable insights into the glaze’s subtle coloration, texture, and the intricacy of the carved decorations. However, no images of the foot sections were available, leaving this feature undocumented.

Recent discoveries of Qingbai dishes and bowls from Batang Kumpeh—a tributary of Sumatra’s Batang Hari River in the Jambi region—can be attributed to the Xicun kiln. Similarly, finely crafted Qingbai bowls with carved and combed motifs, recovered from the Lingga wreck, bear strong stylistic parallels to examples illustrated in Xicun kiln publications. However, the glaze on these shipwreck pieces exhibits a distinct grayish undertone, differing from the shards observed at the Guangzhou City Museum. While further research is needed to confirm their precise origin, they are almost certainly products of Guangdong kilns and unlikely to have originated from the Chaozhou Bi Jiashan kiln.

The production volume of Xicun Qingbai wares was relatively limited compared to the kiln’s green-glazed output. In contrast, ceramics from the Chaozhou Bi Jiashan kiln appear in far greater quantities, as evidenced by their frequent presence in shipwreck assemblages across the region.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Xicun Qingbai Sherds in Guangzhou City Museum | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Three Xicun Qingbai plates with carved and combed floral decoration. From the Batang Kumpeh site in Jambi. | |

|

|

|

|

| Two Qingbai wares from the Lingga wreck. The vessel form and style of decoration are similar to those illustrated in the Xicun Reports. | |

|

|

|

|

| Two

Qingbai ware tall boxes recovered from the Lingga Wreck

feature carved and combed stylized floral motifs on their

lids. While these pieces were likely produced in the Xicun

kiln, nearly identical examples have also been attributed to

the Bi Jiashan kiln in Chaozhou Attribution is further complicated by contemporaneous versions from Nanhan, which share overlapping stylistic traits. Distinguishing between these production sources demands specialized expertise and thorough comparative analysis of materials, techniques, and decorative patterns. |

|

4 Xing-inspired wares

The Xing ware white-glazed bowl, characterized by its thickened lip, was a distinctive ceramic form of the Tang dynasty. The abundance of these bowls found in Southeast Asia underscores their enduring appeal, evidenced by a remarkably long production cycle. During the Northern Song dynasty, the thickened lip remained a feature, but the disc-like *yu-bi* (玉璧底, "jade disc") foot was replaced by a square-cut foot with varying heights. The form also evolved from a shallow shape to deeper profiles during this period. Meanwhile, kilns at Xicun produced similar thickened-lip bowls, primarily in green glaze, though qingbai and brown-glazed variations were also crafted.

|

|

| A thickened lip qingbai bowl from Xicun kiln site |

|

|

|

Two

examples of thickened lip bowl from the Linga wreck. The bottom bowl

with traces of spiral marks on the outer wall could be from the Xicun

kiln. Bowls with similar characteristics are illustrated in the Xicun

Reports. Two

examples of thickened lip bowl from the Linga wreck. The bottom bowl

with traces of spiral marks on the outer wall could be from the Xicun

kiln. Bowls with similar characteristics are illustrated in the Xicun

Reports.The top bowl has a more well-form foot and glaze quality. The characteristics are similar to qingbai wares from Chaozhou Bi Jiashan kiln. |

|

|

|

| A light yellowish-green glazed thickened lip bowl from the Xicun kiln. | |

|

|

|

Examples of Yaozhou style impressed floral bowls from the Xicun kiln exhibited in Guangzhou City Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

Example of Xicun kiln Yaozhou-inspired shallow bowl with impressed floral decoration. |

|

|

|

Fragment purported from a well in Guangdong

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Northern Song Xicun kiln Yaozhou-inspired bowls. From the Batang Kumpeh site in Jambi. | |

|

|

| Yaozhou-inspired green-glazed fragment with molded decoration |

|

| Brown glaze ribbed neck bottle. Left excavated from Xicun kiln and exhibited in the Guangdong Shi Museum. The other is similar in form and likely from Xicun too. It was exported to Indonesia. |

|

|

| Two brown glaze bowls with a band of white glaze rim from the Lingga wreck. A similar one found in Xicun kiln is shown on bottom right. |

|

|

| Northern Song Xicun Brown glaze cover box and bottle from a wreck near Singkep Island |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Xicun brown-glazed wares found in River Batang Kumpleh in Sumatra's Jambi. | |

|

|

| Small lead yellow-glazed phoenix-head ewer recoved from Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi.. The form matches the green-glaze ewers from Xicun kiln | |

|

|

| A lead green-glazed censer found in Guangzhou. | |

|

|

| Green-glaze bowl samples from Huizhou Dongping kiln | |

|

|

| A small, light greyish-green glazed jar that would typically be attributed to Xicun. However, the white slip application on the body suggests it may instead originate from the Dongping kiln. | |

Bi Jiashan Song Kiln

Situated at the western foot of Bijia Mountain in eastern Chaozhou,

the Bi Jiashan Song Kiln extends approximately 2 kilometers from Hutou

Mountain in the north to Yinzi Mountain in the south. Locals still refer to

the area as "Hundred-Kiln Village."

Bi Jiashan No. 10 Kiln Site

Since 1953, archaeological teams from the Guangdong Provincial Museum

and Chaozhou have conducted multiple excavations at the site, often

alongside infrastructure projects. Over 11 kilns have been uncovered,

including stepped and sloped dragon kilns. The most significant, Kiln No.

10, measures 78 meters in length and about 3 meters in width. Though its

head and fire chamber have suffered damage over time, key structural

elements—including the kiln walls, tail, fire wall, and stepped partition

beams—remain remarkably intact.

Bi Jiashan Qingbai Ceramics

The kiln produced a

diverse range of ceramics, primarily utilitarian ware such as bowls, plates,

ewers, bottles, jars, saucers, covered boxes, cups, lamps, stoves,

washbasins, pillows, and human and animal figurines. While it featured

various glaze styles, Qingbai ware was its most prominent output. Large

quantities of Bi Jiashan Qingbai ceramics have been found across Southeast

Asia, with notable recent discoveries from the Lingga wreck and distinctive

forms—such as fish-shaped ewers and human figurines—retrieved from the

Batang Hari River in Jambi, Sumatra.

|

|

| A Qingbai fish-shaped ewer on display at Yi Taoxuan (颐陶轩), a private museum in Chaozhou. | |

|

|

| A group of qingbai fish-shaped ewers found in River Batang Kumpeh, a tributary of Batang Hari in Sumatra's Jambi. | |

|

|

| Two qingbai fragments of phoenix-head ewer. On the left an example found in Chaozhou and on display in Yi Taoxuan, a private Museum in Chaozhou. The other was found in Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi. | |

|

|

| Three qingbai heads from human-shaped ewers at Yi Taoxuan, a private Museum in Chaozhou. | |

|

|

| A qingbai human-shaped ewer from the River Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi. | |

|

|

| On the left, two fragments of Qingbai censer at Yi Taoxuan, a private Museum in Chaozhou. | |

|

|

| A qingbai fragment of a censer. Likely Bi JIashan or Dongping kiln. | |

|

|

| A Bi JIashan kiln qingbai jar with 4 lugs and body adorned with opposing lotus petals carved in high relief. | |

|

|

| Two qingbai dishes with incised stylised floral design at Yi Taoxuan, a private Museum in Chaozhou. | |

|

|

| A qingbai dish adorned with incised stylised floral decoration. From an unknown wreck near Belitung Island. | |

|

|

| Three Lingga qingbai bowls adorned with carved striation. The glaze texture, colour and the clay body are similar to the Bi Jiashan sherds. | |

|

|

| A qingbai floral-shaped bowl from River Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi. Likely a product of Bi Jiashan kiln. | |

|

|

| Three Lingga wreck qingbai ribbed-neck vases. The one on the right is likely from Bi Jiashan kiln. The other two could be from unidentified Guangdong kilns. | |

|

|

|

| A Bi JIashan kiln qingbai ribbed-neck vase. | |

.jpg) |

|

| An impressed, well-potted Lingga wreck Bi JIashan qingbai jar. | |

|

|

| A Bi JIashan kiln dog figurine from River Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi. | |

Archaeological surveys of the Qishi (奇石) and Wen Touling (文头岭) kilns in Guangdong confirm that the brown glaze jars recovered from the Lingga and Pulau Buaya shipwrecks originated from these sites.

Jars from these kilns typically feature impressed floral decorations arranged in various patterns.

Some bear stamped reign marks, with the earliest found at the kiln site dating to the Zheng He reign, such as “the sixth year of the Zheng He reign” (政和六年). Additionally, jars with reign marks like 乾道 (1165–1173 A.D.) and 淳熙十年 (1183 A.D.) provide further evidence that production continued into the latter half of the 12th century.

|

|

| A Lingga wreck green glazed jar with impressed floral motif on the shoulder. A product of Nanhai Qishi or Wen Touling kiln. |

|

| A brownish green glazed jar with impressed floral decoration from the River Batang Kumpeh in Sumatra's Jambi. A product of the Nanhai Qishi or Wen Touling kiln.. |

|

| Fragment of Big Jar from Nanhai Qishi kiln and with Zhenghe 6th year mark |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rubbings of the impressed markings and drawing of the storage jar based on the finds in the Nanhai Qishi kiln | |

The rise of Guangdong ceramics during the Northern Song Dynasty was driven by a combination of geopolitical shifts, maritime advancements, and strategic innovations by kiln operators. As overland trade routes declined, the Song government’s emphasis on maritime commerce positioned Guangdong as a key supplier of export ceramics, filling the gap left by declining Yue, Changsha, and Xing kilns.

By the mid-11th century, Guangdong kilns diversified their production, incorporating influences from Yue, Yaozhou, Xing, and Jingdezhen while maintaining their own distinctive styles. This adaptability allowed them to dominate Southeast Asian trade networks, as evidenced by shipwreck discoveries in Indonesia and archaeological finds in Sumatra’s Jambi region.

The success of Guangdong ceramics was not solely due to technical prowess but also to a well-executed business strategy—offering a variety of ceramic types at competitive prices while leveraging their proximity to major ports for efficient distribution. This innovative approach marked Guangdong’s golden period in trade ceramics, solidifying its reputation as the leading exporter of Song Dynasty ceramics well into the 12th century.

The wealth of archaeological evidence, from shipwrecks like Cirebon, Intan, Lingga, and Pulau Buaya to excavations at Xicun, Bi Jiashan, and Nanhai kilns, continues to reveal the profound influence of Guangdong ceramics on global trade. These discoveries not only highlight China’s dominance in maritime commerce but also underscore the lasting legacy of Song Dynasty ceramics in shaping the material culture of maritime Asia.

Written by: NK Koh (16 Nov 2012), rewritten on 20 Feb 2025

References:

1. Ceramic Finds from Tang and Song Kilns in Guangdong

2. Guangdong Ceramics from Butuan and other Philippine sites

3. A Ceramic Legacy of Asia's Maritime Trade - Song Dynasty Guangdong Wares and other 11th- -19th Trade Ceramics found on Tioman Island, Malaysia

4. The Pulau Buaya Wreck

5. 广州西村古窑址 -文物出版社出版

6. 广州西村窑 - 香港中文大学中国考古艺术研究中心出版