In the early Tang Dynasty (7th century), China’s ceramic industry faced stagnation, marked by scattered kiln sites, uneven geographic distribution, and rudimentary techniques. The absence of large-scale production centers reflected a society emerging from post-war recovery. By the mid-Tang (8th–early 9th century), however, technological breakthroughs—most notably the widespread adoption of saggar firing (protective clay containers shielding wares during kiln firing)—revolutionized production. This innovation dramatically improved quality and consistency, catalyzing the rapid emergence of kiln clusters around Shanglin Lake and expanding to Baiyang Lake, Liduhu Lake, and Shangyu. These interconnected hubs laid the foundation for Yue ware’s later dominance.

The late Tang (9th–10th century) marked the golden age of Yue ware, epitomized by the famed “secret-color porcelain” (mise ci), renowned for its lustrous, jade-like glaze. To meet imperial demands, tribute kilns were established at Shanglin Lake. Under the Wuyue Kingdom’s Qian family during the Five Dynasties (907–960), mise porcelain became a key diplomatic instrument, mass-produced to secure political alliances. Production continued to expand, reflecting growing domestic and international demand.

Yue celadon from Shanglin Lake served both imperial and everyday functions, becoming a cornerstone of maritime trade. By the late Tang, Yue ware was exported via Mingzhou Port, reaching the Persian Gulf, Southeast Asia, and Africa—cementing China’s pivotal role in early global ceramic commerce and cross-cultural exchange.

However, by the mid-Northern Song (1023–1127), the Yue Kilns faced steep decline. Despite earlier triumphs, they failed to innovate, while competitors such as Yaozhou, Ding, and Jingdezhen kilns surpassed them in quality and popularity. By the late Northern Song, only a few kilns near Shanglin Lake remained, relying on crude open-flame firing and repetitive designs—a stark contrast to their earlier sophistication.

|

| Some examples of Yi bi base |

|

|

| Tang bi-base bowls from Shanglin Lake kiln |

|

| Bowls separated by clay lumps in Saggar |

Emerging in the mid-9th century as tribute for the Tang court, Mise ware is evidenced by:

|

|

|

| Famen Si Mise dishes andeight-sided vase |

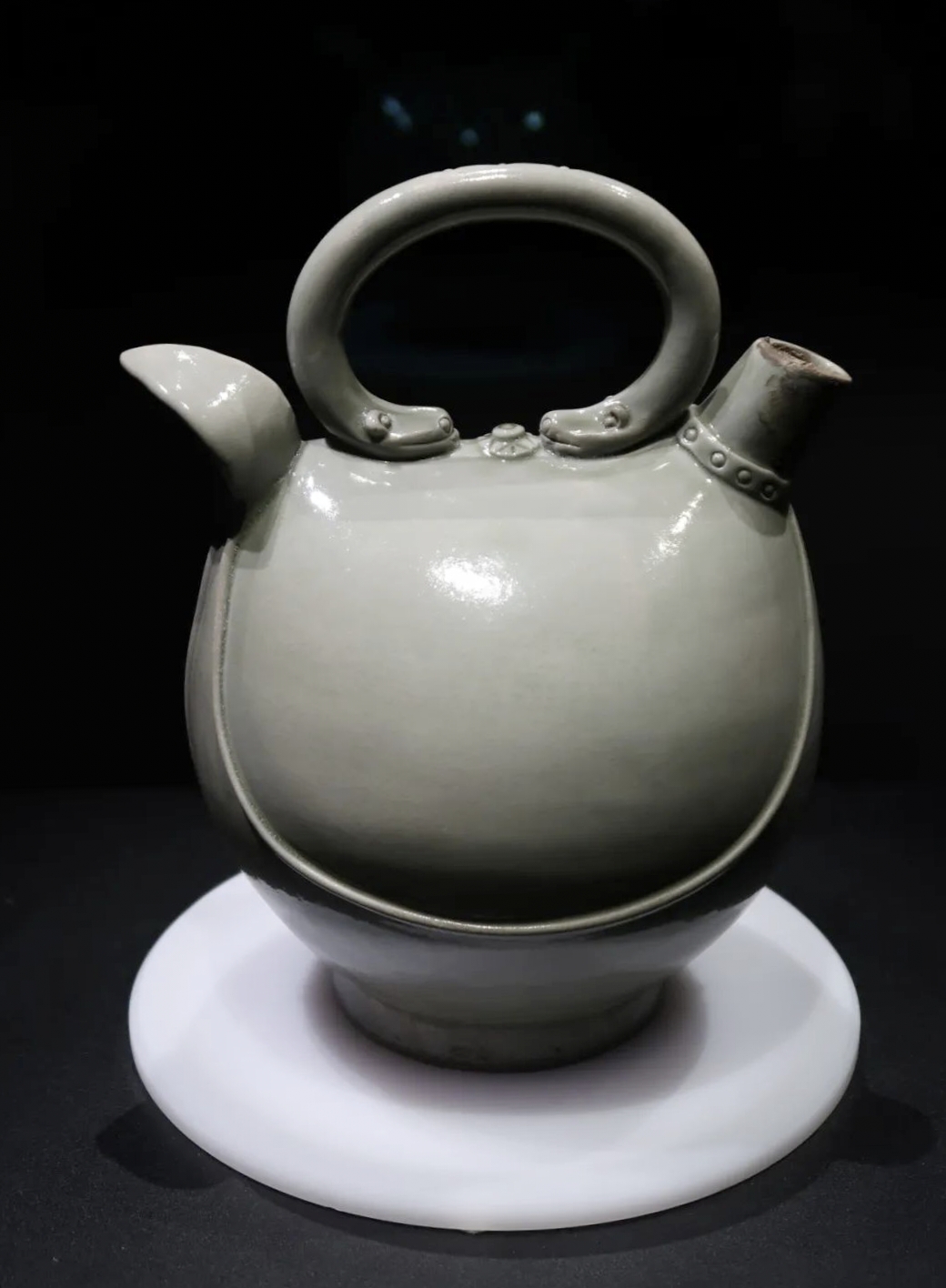

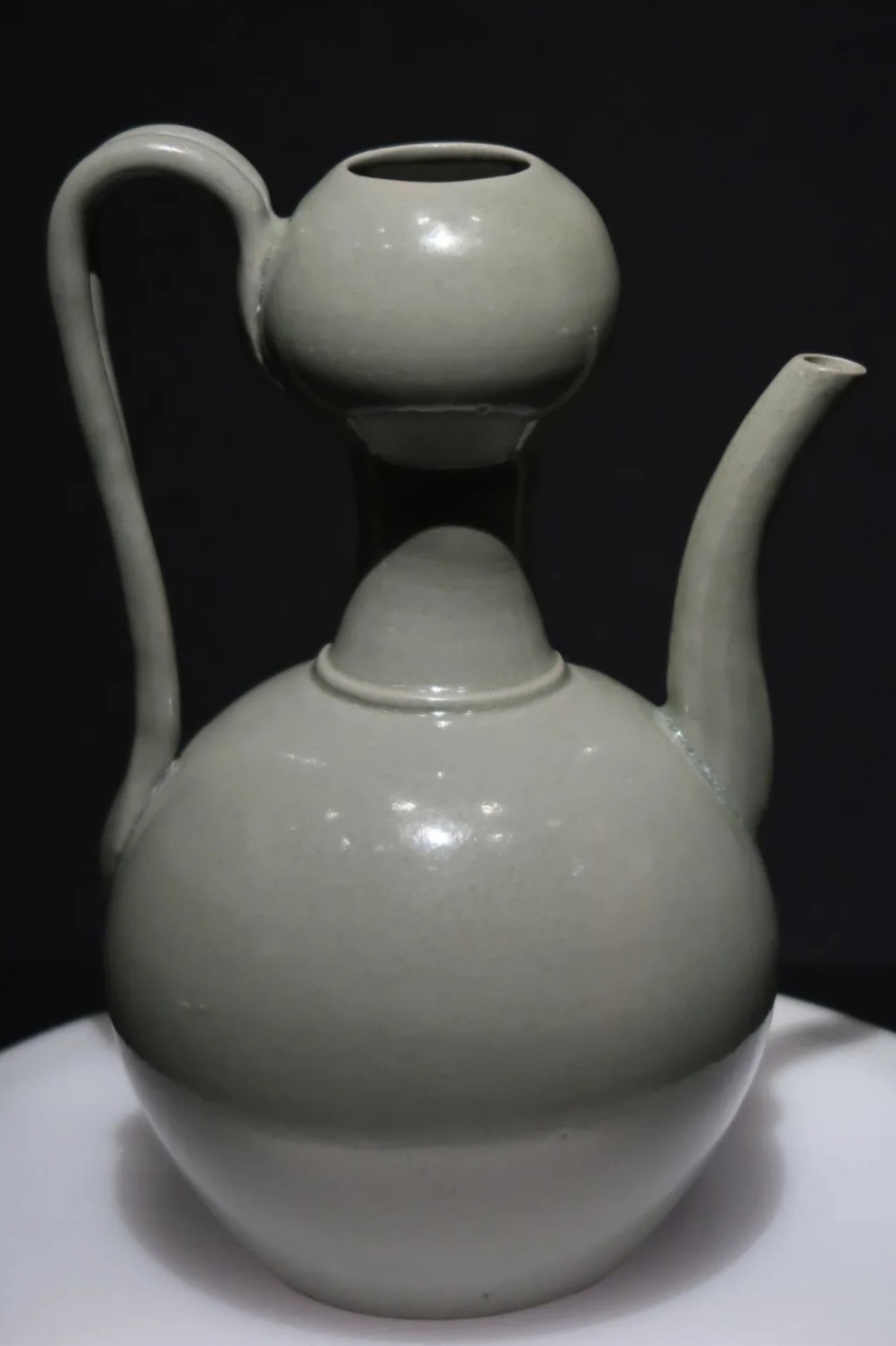

| Tang Yue Vessels exhibited in Cixi Museum |

The Yue wares recovered from the Indonesian Belitung wreck, dated to around 823 A.D. (based on a Baoli reign mark on a Changsha bowl), showcase some of the period's most representative Yue wares.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Refined Yue wares from the Belitung wreck |

Under the Wuyue Kingdom’s Qian family, Yue Kiln production flourished, particularly around Shanglin Lake (Cixi, Zhejiang), monopolizing the manufacture of high-quality wares for tribute, diplomacy, and export.

|

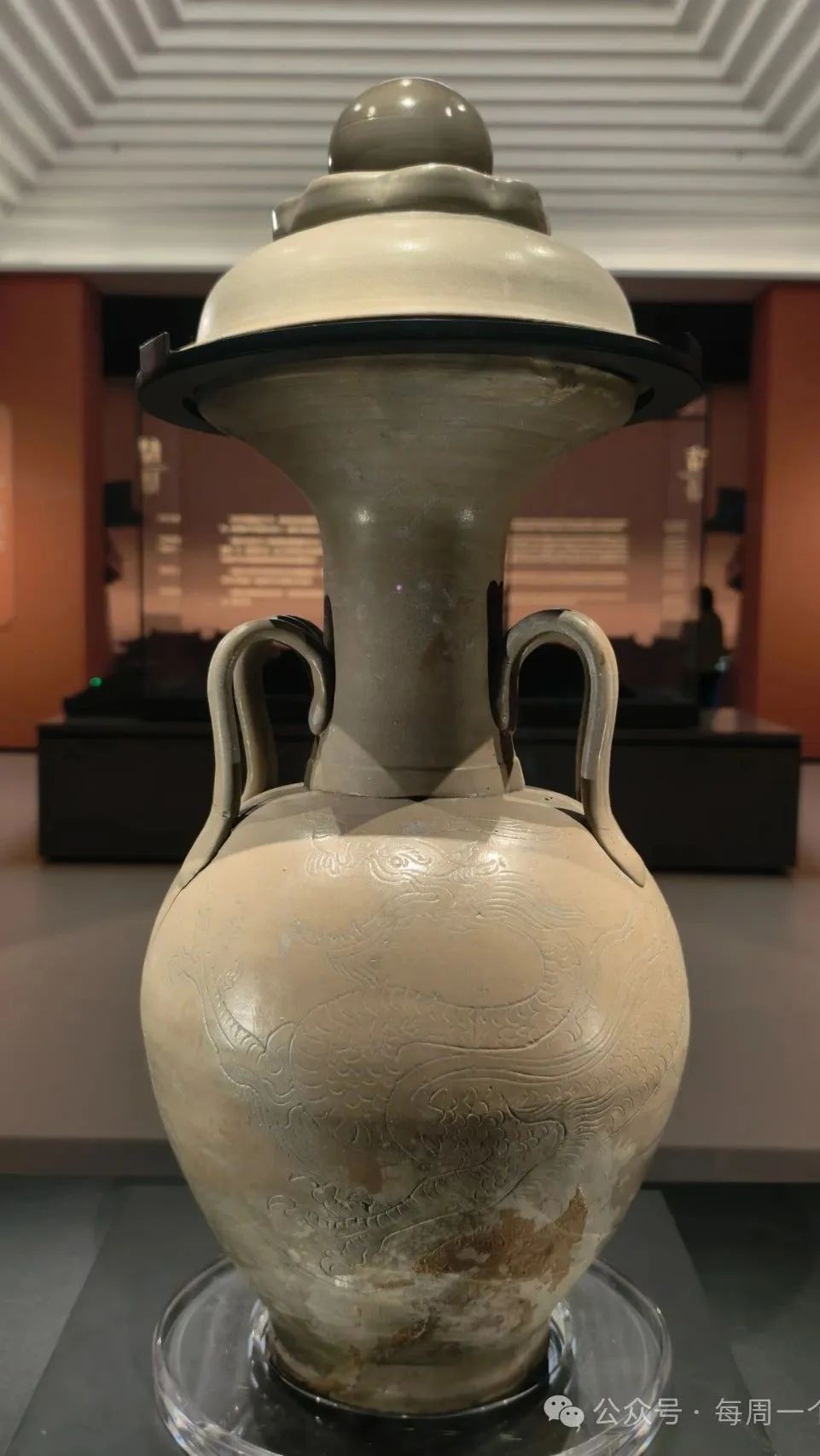

| Mise dragon jar from the tomb of Qian Yuan Guan |

|

|

| Mise wares with iron-brown decoration from the tomb of Shui Qiu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Group of Mise wares from the tomb of Qian Liu |

Yue wares from the Indonesian Cirebon wreck, dated to the transition from Five Dynasties to Northern Song, reflect the period's range and quality of vessels.

|

| Refined Yue wares from Cirebon wreck |

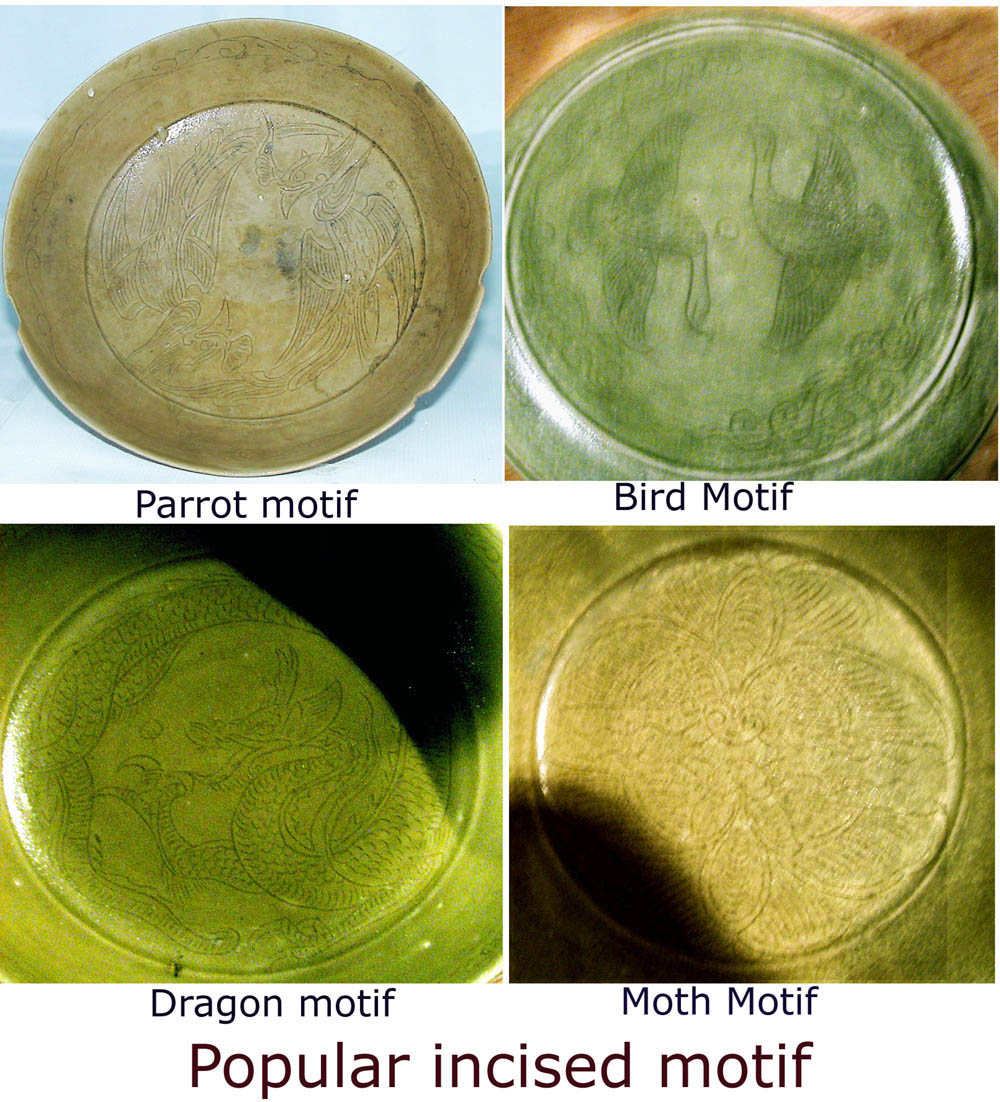

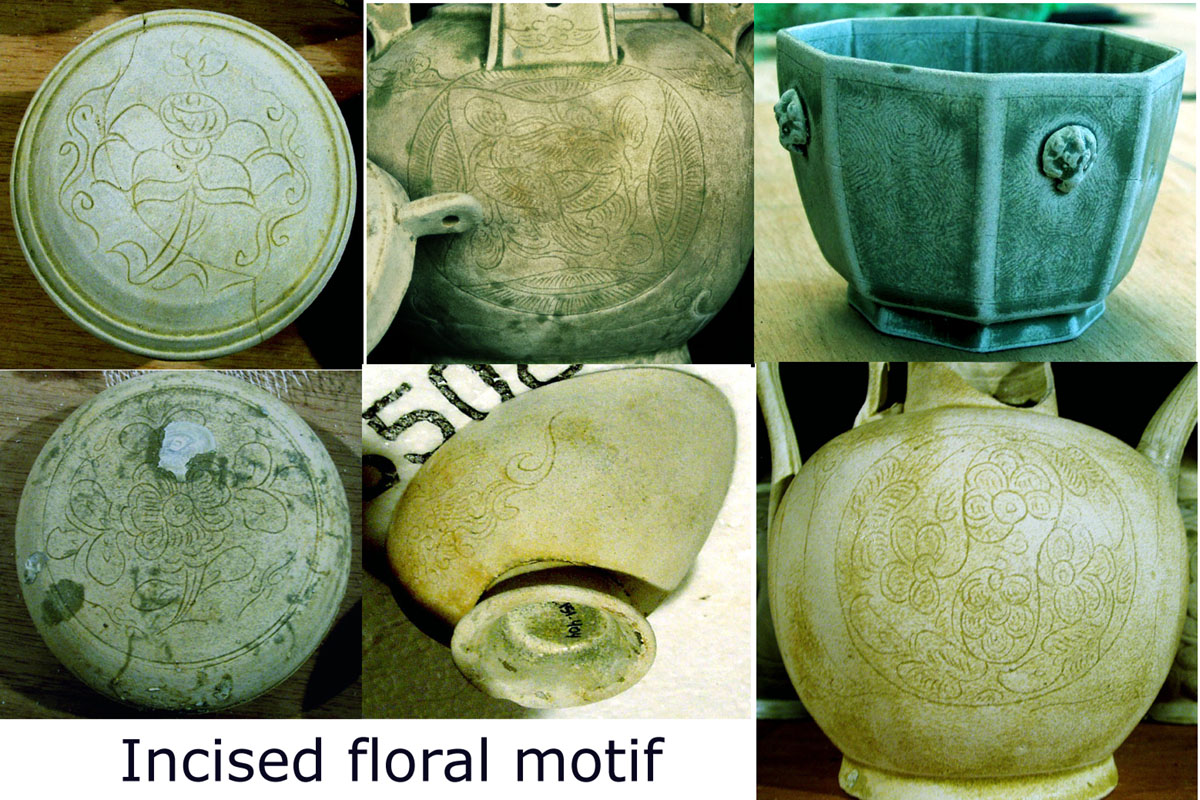

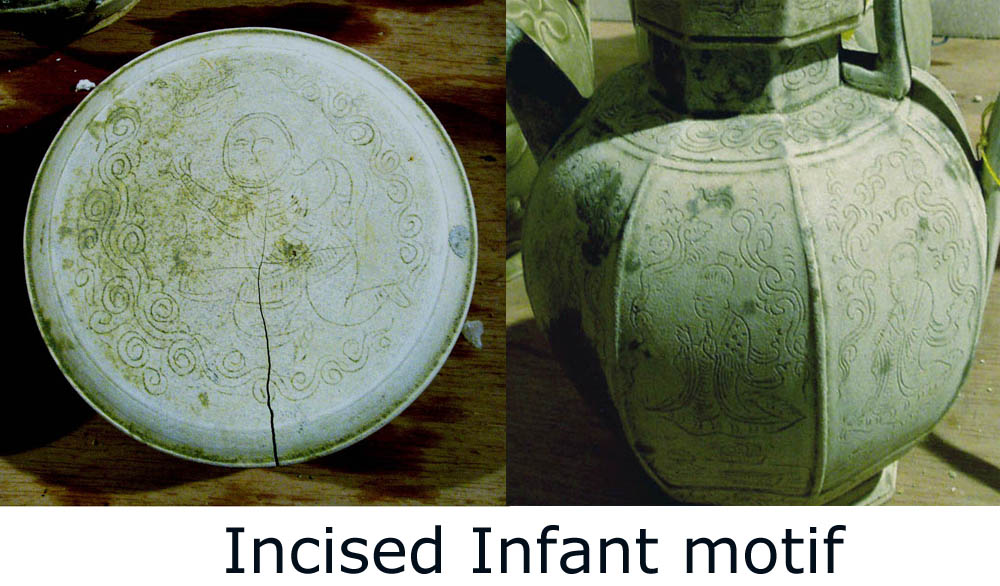

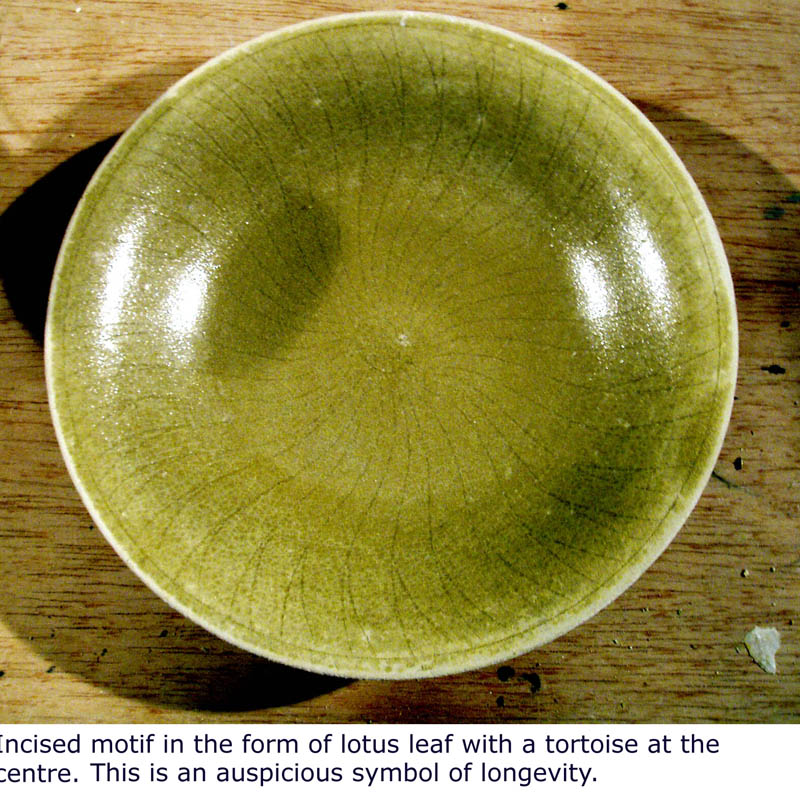

Important discovery of Mid Northern Song phase Yue kiln at the Dong Qian lake Shang Shui Ao kiln (东钱湖上水岙窑)in 2016. The quality of the vessel is very high and the variety wide ranging, including bowl, plate, cup, censer, bowl with stand, brush washer, vase, multi-layered boxes, pillow, 5 tubes oil lamp and etc. The decorative technique highly sophisticated incorporating carving/incising, high/low relief carving, applique work, open work and etc. There is rich repertoire of motifs comprising lotus, peony, other vegetal forms, parrot, mandarin duck, crane, phoenix, sparrow, dragon, makara, fish, wave and etc. Incised characters found on base include “大”“内”“千”“周置”“大吉”“曾州”“上清”.

Although intricate carvings once thought exclusive to the Five Dynasties persisted into early Song, by the late Northern Song, Yue ware’s prestige had faded as innovative kilns like Jingdezhen—producing high-fired porcelain with cobalt underglaze—rose to prominence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Some Yue artifacts recovered from the Shang Shui Ao kiln |

|

|

|

|

| 5 Dynasties/Northern Song Yue fragments found in Brunei archaeological sites (Photo credit: Hann Maidin of Brunei Museum. |

|

|

| Sherds with sketchily carved decoration dating to Mid Northern Song |

When discussing the history of Yue ware production, the general consensus is that the kilns ceased production by the late Northern Song. However, Chinese archaeologists have discovered an interesting development at Cixi (慈溪), the main Yue ware production center, during a brief period in the early Southern Song. Excavations revealed that some kilns, such as those at Si Longkou (寺龙口), Kai Dao Shan (开刀山), and Di Ling Tou (低岭头), continued producing greenware. These ceramics were used for a short time by the imperial court during the Southern Song period.

Two distinct categories of this ware have been identified:

|

|

Examples with carved/combed decoration influenced by Ding ware. |

|

It is evident that porcelain-making technology from Northern China—specifically Henan and Hebei—was transferred and adopted in the South. Potters fleeing south after the fall of Luoyang to the Jin army likely contributed to this transition.

After the collapse of the Northern Song in 1127, Emperor Gaozong fled Kaifeng and was relentlessly pursued by the Jin army until he finally established his capital in Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in 1140. Despite this turmoil, the imperial court continued to hold ritual ceremonies, and porcelain played a role in these events.

The recently discovered Zhongxing Lishu (中兴礼书), a book on Southern Song court rituals, records that Yuyao (余姚) and Pingjiang (平江) (modern-day Jiangsu) were commissioned to produce ritual vessels on several occasions. Geographically, Yuyao was part of Cixi (now a county-level city), reinforcing the link between these kilns and imperial porcelain production.

Over the past 30 years, extensive construction in Hangzhou has transformed it into a modern cosmopolitan city. During this process, numerous ancient ceramic fragments were unearthed and eagerly collected by Chinese enthusiasts. Among these were Cixi kiln Yue-type greenwares with Ding-style carved decoration. Some pieces bore incised marks such as Yu Chu (御厨, "Imperial Kitchen") on the outer base, along with other inscriptions associated with the imperial court, including Yuan (苑), Dian (殿), Gui Fei (贵妃), and Ci Ning Dian (慈宁殿). These marked examples were discovered in 2009 at the former site of the Southern Song state guest house (都亭驿).

|

|

|

|

| Southern Song Yuyao Kilns – Examples from the State Guest House Site |

Conclusion

The story of Tang–Song Yue green-glazed ware is a testament to the resilience, ingenuity, and artistry of early Chinese ceramic traditions. Zhejiang was the birthplace of green-glazed ware production, with its origins traceable to the Zhou Dynasty's proto-porcelain. After a long period of evolution, mature green-glazed porcelain finally emerged during the Eastern Han Dynasty. However, following the turmoil of the Southern Dynasties, the quality of these products declined significantly. Archaeological surveys reveal that in the early Tang period, only scattered kilns produced crude green wares. Yet by the mid-Tang, a remarkable revival had begun, and Yue ware rose to international prominence during the late Tang and Five Dynasties periods, achieving technical and aesthetic excellence in the famed mise celadon.

The evolution of Yue ware reflects not only advancements in kiln technology and artistic design but also broader socio-political shifts, including imperial patronage, diplomatic exchange, and the demands of a growing global trade network. Although Yue ware eventually declined under pressure from more innovative kilns such as Yaozhou, Ding, and Jingdezhen during the Northern Song, its influence endured—evident in later revivals during the Southern Song and the lasting appreciation for its refined, jade-like glazes.

Ultimately, the legacy of Yue ware is deeply woven into the broader narrative of Chinese ceramic history, standing as a symbol of how art, technology, and commerce intersected to shape one of China’s most influential and enduring cultural exports.

Written by : NK Koh (11 Mar

2025)